Absent a full defense budget request from the White House nearly six months into President Donald Trump’s tenure, lawmakers are taking matters into their own hands.

House appropriators on June 9 took the unusual step of unveiling an $831.5 billion defense funding measure, even before the Trump administration has said how it intends to spend the money. The legislation includes $228 billion for the Air Force and $29 billion for the Space Force. Last week, another House appropriations subcommittee also approved nearly $4 billion for military construction across the two services.

If passed into law, the Department of the Air Force would receive $261 billion from the House—a slight uptick from the $257.1 billion Congress provided the Department of the Air Force in 2025. It is also roughly equal to the topline amount the Trump administration had indicated it would seek for 2026.

Not all the funds earmarked for the Department actually end up supporting Airmen and Guardians. About 20 percent of the Department of the Air Force Budget each year passes directly to other federal agencies, largely the National Reconnaissance Office, a defense intelligence agency whose missions are tightly linked to the Space Force. It is not yet clear how much of this “pass-through funding” is included in the draft legislation.

Rep. Ken Calvert (R-Calif.), the defense appropriations subcommittee chairman, said in a release that the proposal is part of a “historic commitment to strengthening and modernizing America’s national defense,” combined with another reconciliation bill to deliver $1 trillion for defense in 2026 for the first time ever. Lawmakers aim to send both the core defense spending bill and its military construction companion on to the full House by the end of the week.

Capitol Hill normally takes its cues from the executive branch. So while Washington has grown used to unorthodox budgeting, with Congress typically failing to pass funding legislation until well after a fiscal year starts, appropriating funds before a budget is submitted is an entirely new twist.

“Unprecedented,” wrote Byron Callan, a long-time defense analyst with Capital Alpha Partners, wrote in his June 9 newsletter. “DoD has not sent Congress a complete FY26 budget request, only an appendix to the ‘skinny budget.’”

The appendix, released by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget May 30, outlined $261 billion in funding for the Air Force and Space Force as well. But it stopped short of including line-by-line details of how those billions would be spent, for instance, on weapons buys or bonus pay. OMB has promised to publish those specifics later this month.

“I know the process to this point has been a little non-traditional, but it is important that we do our jobs as appropriators and get moving on this critical legislation,” Rep. John Carter (R-Texas), who chairs the military construction subcommittee, said in a June 5 news release. “As this process unfolds and we receive further budget documentation, we will take it under consideration including those proposals aimed at improving efficiencies.”

A committee summary of the House defense spending bill offers more insight into how the sum might be doled out.

Lawmakers would boost spending on procurement for new air and space systems and for development of military space projects, but they would shrink funding for the personnel and operations-and-maintenance accounts across both the Air Force and Space Force.

The defense spending bill supports the Air Force’s major programs, including the F-35 Lightning II, the next-generation F-47 fighter, and the B-21 Raider bomber, according to the summary. Lawmakers also backed the 3.8 percent military pay increase proposed by the White House.

The bill also shields the C-40 executive airlift fleet from retirement, protects the Air Force Reserve’s “Hurricane Hunters” unit while allowing its Airmen to take on other missions outside of hurricane season, and blocks the Space Force from absorbing the National Reconnaissance Office.

- $3.9 billion for missile warning and tracking systems

- $2 billion for 11 national security space launches

- $1.8 billion for satellite communications upgrades

- $680 million for two new GPS satellites

- $360 million for GPS enterprise upgrades

- $7 billion in classified space programs

They would block, however, the Air Force’s plan to retire F-15 fighters and the high-flying U-2 reconnaissance plane, retaining those aircraft until the service has replacements in hand. The package directs the Air Force to restore three U-2s at a cost of $55 million. The Air Force, arguing the aging planes are no longer viable in a peer competition, had intended to rely on surveillance satellites for digital photos rather than the Cold War-era U-2s.

The House bill also includes:

- $8.5 billion for 69 F-35 fighters, including $4.5 billion for 42 Air Force jets, and another $2.2 billion for continued development

- $3.8 billion for B-21 bomber procurement, plus another $2.1 billion for development

- $3.2 billion for F-47 fighter development

- $2.7 billion for 15 KC-46 tankers

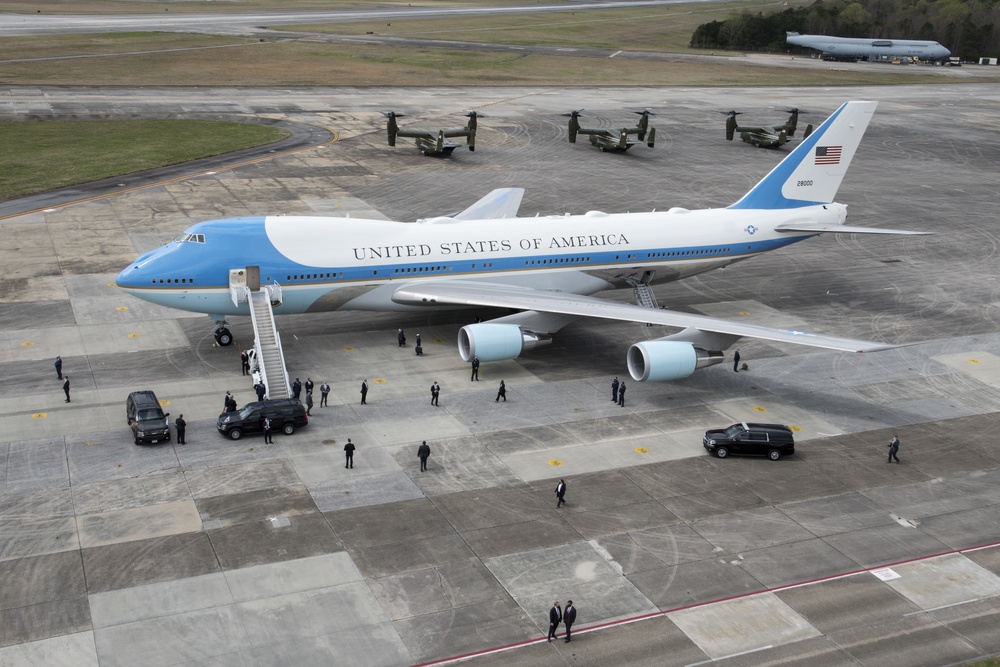

- $1.8 billion to develop a new Survivable Airborne Operations Center jet

- $500 million to continue research on the E-7 airborne target tracking plane

- $483 million for the Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile

- $474 million for two EC-37B electronic attack aircraft

As for the Space Force, lawmakers would put $4.1 billion toward pulling the service’s programs into the sweeping “Golden Dome” missile-defense vision championed by Trump. The smallest military branch would also receive:

Appropriators are pressing the Pentagon to find $7.8 billion in potential spending cuts, and they codified in their bill nearly $4 billion in savings identified by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency team.

Democrats on the committee cited those cust as amounting to up to 1 percent of defense programs across the board, including $2 billion apiece for personnel and readiness. The cuts would not affect intelligence activities.

Callan said the changes could target operations and maintenance spending and hurt acquisition.

“We don’t see offsetting investment funds added to make a smaller DoD workforce more productive,” he wrote. “While attractive in concept, these sorts of cost savings could potentially slow DoD program oversight and contracting.”

Neither the House Appropriations Committee nor the White House responded to requests for comment about how lawmakers settled on the dollar amounts included in the bill or whether they match the Pentagon’s forthcoming request.

Other lawmakers are growing impatient with the hold up on spending legislation, one of Congress’s core responsibilities. With only 115 days until the next fiscal year begins Oct. 1, this may be the longest Congress has ever had to wait for an annual defense funding blueprint from the executive branch, noted Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), the top Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine are scheduled to appear before both House and Senate appropriators this week to discuss the 2026 budget.