How the U.S. can counter China’s size and other advantages.

Decades of force cuts and deferred modernization have left the U.S. Air Force unable to simultaneously deter nuclear attacks, defend the U.S. homeland, and defeat Chinese aggression at acceptable levels of risk. Years of insufficient resources have also eroded the Air Force’s ability to conduct long-range, penetrating attacks against China’s centers of gravity and deny the operational sanctuaries the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) needs to generate air and missile attacks against U.S. bases in the Pacific. The net result: China holds a decisive advantage in combat mass that cannot be overcome by the United States and its allies and friends.

It is not enough for the U.S. to simply prevent the PLA from seizing ground on the shores of Taiwan. That by itself will not guarantee victory. A war-winning strategy must also deny sanctuaries to the PLA—including sanctuaries on China’s mainland—and enable U.S. forces to degrade China’s ability to launch long-range air and missile salvos that could cripple U.S. joint force operations in the Pacific.

But such a war-winning strategy requires a war-winning force structure to ensure the U.S. has the capability and capacity to defeat a Chinese invasion of Taiwan and deny the PLA sanctuaries from attacks.

The Air Force will soon field next-generation bombers and fighters with the range, survivability, and payload capacity to deny sanctuaries to PLA forces wherever they are. But these will be of little value unless the service acquires enough of them. Multiple studies have concluded the USAF needs at least 200 B-21 Raider bombers to meet operational demand for penetrating strikes. Stealthy F-47s and F-35As, supported by uncrewed Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) and F-15EX stand-off strike aircraft, are also required at scale. Yet the Air Force is acquiring new fighters below the sustainment rate necessary to maintain its combat inventory. Delaying or truncating any of these acquisition programs now would create a fragile force unable to take the fight to China—a force incapable of achieving peace through strength or of winning should deterrence fail.

Deny Sanctuary

History has repeatedly demonstrated the imperative to deny operational sanctuaries that enable adversaries to husband resources, produce war materiel, train replacement warfighters, secure military leadership, and protect their lines of communication. Because freedom from attack is crucial to enable the freedom to attack, denying sanctuaries is an essential element of any successful warfighting strategy.

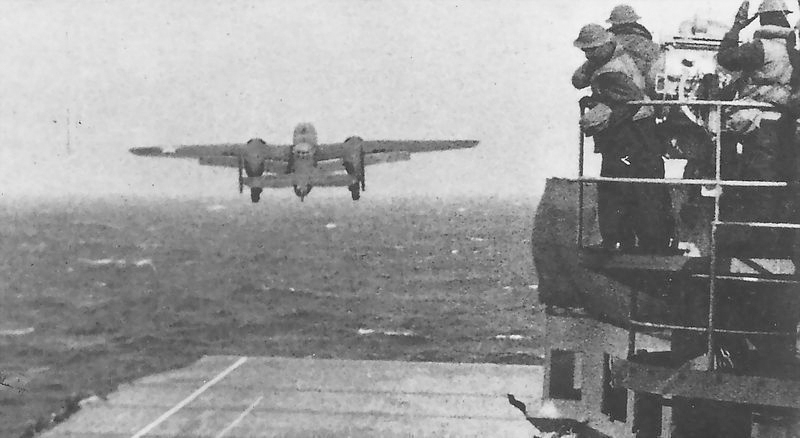

The daring April 1942 Doolittle Raid on Japan highlights the strategic value of denying sanctuary. Although it inflicted only minimal damage, the Doolittle Raid drove Japan’s high command to withhold four fighter groups for home island defense, stretching Japan’s remaining forces across its occupied territories in the Western Pacific. By 1944, U.S. long-range B-29 bombers were devastating Japan’s war industry, training sites, and military bases—denying the sanctuaries that had enabled Imperial Japan’s expansionist aggression in the first place. Ultimately, it was those long-range penetrating attacks that pushed Japan to its unconditional surrender in August 1945. In Europe, long-range B-17 Flying Fortress and B-24 Liberator bombers likewise denied sanctuary to Germany, disintegrating their war industries, will, and combat power.

Nearly five decades later, Operation Desert Storm likewise demonstrated how an air campaign can deny sanctuary to an adversary. Employing an effects-based strategy to attack multiple centers of gravity deep within Iraqi territory, planners leveraged stealth and precision-guided munitions to paralyze the Iraqi army’s ability to wage war. No area or target in Iraq was off-limits, and the overwhelming pace and volume of airstrikes utterly collapsed the Iraqi military. The USAF campaign to deny sanctuary resulted in one of the most stunning military successes in history.

Penetrating airpower, however, is only effective if national leaders are willing to employ it. History provides many unfortunate examples where militaries that are unable or unwilling to deny sanctuary were reduced to waging force-on-force attrition campaigns, a self-defeating form of warfare.

Consider President Harry S. Truman’s desire to limit the Korean War. By restricting U.S. military operations, he effectively allowed China to support North Korea’s forces nearly unhindered. The United States also tightly restricted targets during the Vietnam conflict, focusing air operations on interdicting fielded forces and reactive, defensive strikes. By ceding the operational advantage and effectively granting sanctuary to North Vietnam and its state sponsors, the United States prolonged the conflict and ultimately failed to achieve its aims.

Today’s Russia-Ukraine war further demonstrates how the inability to deny sanctuaries leads to strategic stalemate. U.S. restrictions on the use of weapons supplied to Ukraine, for example, have shielded Russian combat forces, command and control, logistics, and rear area support services, providing Russia the sanctuary’s asymmetric advantage. As President Donald Trump said, “It is very hard, if not impossible, to win a war without attacking an invader’s country. It’s like a great team in sports that has a fantastic defense, but is not allowed to play offense. There is no chance of winning!”

The lesson from these historical examples is clear: Fighting a war of attrition and interdiction unnecessarily draws out conflicts and leads to suboptimal outcomes. Denying sanctuary to an adversary is a powerful way to rapidly prevail in a conflict—and only airpower can conduct strategic attacks at the scale, tempo, and concentration required to do so and collapse an adversary’s ability to sustain combat operations. Yet to do that, an air force must be resourced with the capabilities, aircraft, and munitions to penetrate adversary air defenses, execute their missions, and return to fly again.

Older, Smaller, Less Capable

Today’s Air Force does not reflect these principles. Among an inventory of 141 bombers, just 19—or 13 percent—are capable of long-range, penetrating strikes. Those 30-year-old B-2 Spirits are the entirety of the nation’s penetrating bomber force. Of the Air Force’s 2,000 fighters, only 20 percent are stealthy F-22s or F-35As. And none boast an unrefueled mission radius exceeding 700 nautical miles. This is not a resilient force that can sustain operations against highly capable adversaries like China; it is too small to absorb aircraft losses in peacetime, let alone in time of war.

By contrast, the PLA Air Force is growing. China now fields the largest aviation force in the Indo-Pacific region, and the third largest in the world, according to the U.S. Air Force. The PLAAF now owns more than 1,900 fighters, including fifth-generation J-20s and more than 225 J-16s that can carry very long-range air-to-air missiles. The PLA is also developing advanced capabilities. Its stealthy, long-range Xi’an H-20 bomber, in development since 2016, could enter production in the next few years. Two sixth-generation fighters, the Shenyang J-50 and the Chengdu J-36, are also in development. The J-36 could be a fighter-bomber hybrid, given the size and apparent volume of its weapons bays.

To course-correct and rebuild the Air Force’s sanctuary-denial capability and capacity, it must field the B-21 as the foundation of its long-range strike family of systems. Air Force leaders have said they need at least 225 bombers—a mix of next-generation stealthy B-21s and nonstealthy B-52Js. The B-21’s advanced stealth—a low-observable flying wing shape, next-generation coatings to absorb radar, and other advanced technologies—give it the all-aspect, broadband stealth necessary to penetrate advanced integrated air defenses. Like the B-2, the B-21 is equipped with systems that can fuse information from multiple onboard and off-board sources and smart mission planning tools to help pilots avoid high-risk threats.

Combined with sixth-generation F-47 fighters and uncrewed CCA, B-21s will vex China’s air defenses with a far more credible challenge. This combination will complicate adversaries’ ability to accurately characterize threats, causing them to expend defensive assets against decoys and other lower-value capabilities instead of piloted aircraft.

Stand-off Combat Airpower Is Not Enough

Rebuilding the Air Force’s bomber and fighter inventory will not be cheap, and air defenses are becoming ever more lethal. That’s why some defense planners are pushing to shift the balance of U.S. forces toward stand-off attack. These planners see stand-off aircraft and weapons as the only viable way to survive in a peer conflict. But such a shift risks an even more fragile USAF force design, one that increases reliance on completing long-range kill chains at an unprecedented scale during a peer conflict.

The problem is that greater reliance on stand-off systems and their long-range kill chains gives adversaries more opportunities to counter U.S. strikes, through both kinetic and nonkinetic means. In the opening days of conflict, when the U.S. would need to complete thousands of long-range air-to-air, air-to-surface, and surface-to-surface kill chains, those risks are greatly increased. Indeed, they are beyond current U.S. Air Force and Space Force capacity. Yet even as these critical kill chains mature technologically, the increased complexity of their sensor networks and datalinks will continue to be vulnerable, increasing opponents’ opportunities to disrupt the flow of information from sensors to shooters.

Shifting toward stand-off attacks also ratchets up the cost of munitions needed to strike a given set of targets. Like combat aircraft, munition costs are determined by technological variables: range, stealthiness, warhead size and weight, and even inflight speed. As these increase, so do weapon costs, with some long-range surface-to-surface missiles costing tens of millions of dollars each. In the case of the U.S. Army’s new Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon, those costs could be far higher.

Cost translates directly into the number of weapons the nation can afford to acquire, and therefore the number of targets it can strike. It also defines the force’s resilience in a protracted conflict.

China, Russia, and other adversaries routinely protect their high-value military assets in hardened shelters. But defeating hardened shelters requires the use of more or larger munitions, while stand-off munitions must, out of necessity, carry smaller and lighter warheads to travel long distances. Even when used in multiples, stand-off weapons may not be able to penetrate hardened and deeply buried facilities. This is why the Air Force acquired short-range penetrating munitions like the 5,000-pound-class GBU-72/B bunker buster bomb and the 30,000-pound GBU-57A/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP). These munitions demonstrated their effectiveness on such targets in Operation Midnight Hammer against Iran’s nuclear facility in June. Only stealthy aircraft can deliver such large penetrating weapons in contested areas.

The inability to reach distant targets is another limiting factor for stand-off attack weapons. The air-launched Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile-Extended Range (JASSM-ER) and its variants acquired by DOD have ranges of more than 500 NM, while the Navy’s Tomahawk cruise missile can reach targets located 1,000 NM or more from their launch platforms. These and other stand-off weapons are critical to preventing a Chinese fait accompli operation to seize Taiwan, but their effective target area coverage would be reduced significantly if they are launched at distances of 800 NM or more from China’s coastline. Such distances would greatly reduce the utility of using stand-off strike platforms alone to deny sanctuary to PLA forces stationed deep within China’s interior.

Restoring Penetrating Airpower

The Air Force is the only U.S. or allied service that operates long-range bomber aircraft. Once it acquires the F-47, it also will be the only one to fly long-range stealthy fighters. Ensuring the USAF has the right mix of nonstealthy, stand-off, and stealthy penetrating aircraft must now be a national imperative. The Air Force has long held that it requires both stand-off and penetrating aircraft and munitions in its force design. Having both in combination poses a more complex threat to opposing forces and increases the Air Force’s options to create war-winning effects.

The Air Force must be properly sized to do three things simultaneously:

- Create war-winning effects in a peer conflict

- Deter nuclear attacks

- Defend the U.S. homeland.

To do all three, the U.S. should procure B-21s at an accelerated rate and acquire at least 200 aircraft. Combined with B-52s that are projected to remain in service until 2050, this would more than double the Air Force’s current long-range strike sortie capacity. This inventory would still be smaller than the bomber force DOD fielded throughout the Cold War.

Similarly, the U.S. Air Force must retain and modernize its F-22 fleet, increase the pace of F-35 procurement, and accelerate F-47 development. From a force mix perspective, the F-47’s unmatched low observability, range, and payload is crucial to rebalancing the service’s combat forces for peer conflict—but it does so only if purchased in volume. Even the most capable F-47 can only be in one place at a given time, which is why far more than 185 F-47s will be needed to meet growing demand for long-range combat airpower—especially in the vast Indo-Pacific theater. F-47s operating with B-21s and other aircraft in the Air Force long-range strike family of systems will be the backbone of DOD’s sanctuary denial force.

The Air Force now has a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rebuild the sanctuary denial capacity that the U.S. military and our allies depend upon. The U.S. Congress should fully fund the Air Force’s F-35 and F-15EX procurement accounts and robustly resource the F-47 and B-21 programs to accelerate their pathway to full production by investing additional funds beyond those planned today. Without that additional funding, the Air Force will struggle to keep both the F-47 and B-21 programs on track.

Together, the B-21 and F-47 can deny sanctuaries to China’s forces and enable U.S. airpower to collapse the PLA’s capacity to sustain large-scale air and missile attacks against allied forces in the Pacific. No other existing or planned U.S. combat systems provide a similar unilateral capacity to strike dynamic targets at the scale and tempo necessary and over the long ranges required to reach high-threat-density areas. The Mitchell Institute recommends:

- The Air Force should conduct cost-per-effect analysis to inform its development of a balanced mix of long-range penetrating and stand-off combat aircraft and munitions. Such an analysis should factor in the entire system-of-systems that long-range kill chains require to be resilient and effective at the scale needed in a peer conflict. Failure to consider all aspects of these kill chains will inevitably distort their actual cost per effect.

- Congress and the Department of Defense should provide the U.S. Air Force with at least $5 billion more per year to nearly double its planned B-21 acquisition and create a bomber force capable of denying operational sanctuaries to the PLA.

- Congress and the DOD should support the acquisition of at least 300 sixth-generation F-47 NGAD fighters as part of the Air Force’s future force design. F-47s and B-21s, working in combination, will be able to strike any target on China’s mainland to deny sanctuary and eliminate capabilities critical to the PLA’s air and missile forces.

- The Air Force should refrain from retiring its stealthy B-2s until a sizable force of B-21s—surpassing 100 aircraft—is fully operational in the 2030s. Maintaining the current force of stealthy bombers would hedge against B-21 program risk and increase the Air Force’s penetrating strike capacity over the next 10 years when the threat of Chinese aggression may be greatest.

- The Air Force should accelerate purchases of current-generation F-35As and F-15EXs to rapidly modernize the fighter force. Acquiring 74 F-35A and 24 F-15EX fighters per year will reverse decades of force cuts and provide a vital hedge against future risk. These aircraft will help create a balanced penetrating and stand-off force mix for conducting long-range precision strikes, including attacks against maritime targets, counterair operations, electromagnetic warfare, and other missions. They will also increase the Air Force’s capacity to team its piloted aircraft with uninhabited CCA to achieve affordable mass—a necessity to help counter the PLA’s combat mass advantage.

Long ranges, large payloads, precision weapons delivery, and survivability remain foundational requirements for modern combat aircraft that are designed to deny sanctuaries. Moreover, U.S. air forces must have enough long-range aircraft and munitions to do so with sufficient tempo and concentration over time. Failing this, the United States could face a costly, bloody, and drawn-out conflict with devastating losses. The United States must make the investments necessary to rebuild the nation’s long-range, penetrating bombers and fighters—or risk losing the next war.