Stealth was a gamble 50 years ago. It’s still a good bet.

S

tealth technology has given the U.S. military an air of near invincibility for the past 35 years. Overwhelmingly successful in the 1991 Gulf War, and heavily refined and improved through several generations since, stealth gives the Air Force its “kick down the door” ability to go anywhere and provide the air dominance relied on by the rest of the joint force.

Retired Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein said he told President Donald Trump in his first term that, because of stealth, “I can hit any target on the planet that you want me to hit, with incredible precision, and there’s nothing the adversary can do to stop me. And that’s not something that our adversaries or allies can say. But you have that.”

Operation Midnight Hammer, in which U.S. aircraft blew past Iranian air defenses and delivered a severe blow to Iran’s nuclear weapons programs in June, was made possible by three types of stealth aircraft—F-22 and F-35 fighters and seven B-2 bombers—all which returned without a scratch.

In the military arena, though, for every measure there is eventually a countermeasure. The demise of stealth has been predicted many times, as new detection techniques and ever-faster computers proliferate. But experts say those predictions are premature, and stealth will remain an essential Air Force tool for decades to come.

Modern stealth dates back to 1975, when the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) awarded Lockheed and Northrop contracts to develop experimental aircraft that would be hard to detect and track. Radar-guided antiaircraft missiles had taken a heavy toll on U.S. aircraft in the Vietnam War, and the Soviet Union was spending lavishly on a massive air defense system meant to build an aerial wall the U.S. combat air fleet couldn’t breach. America needed a new edge.

The Soviet Union almost spent themselves into obscurity trying to counter stealth.

—Former Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Goldfein

If successful, stealth would allow American aircraft to overfly the world’s toughest, most heavily defended targets, and render Moscow’s massive national investment in air defenses largely obsolete. Stealthy fighters and bombers could approach targets without being detected, then launch their weapons and leave the area before being engaged by defenders.

The idea was to lower an enemy’s odds of success at every step in the kill chain: reduce the chance of detection; reduce the chance of tracking if detected and reduce the chance of bringing a weapon to bear if tracked.

Lockheed’s Skunk Works advanced products unit was picked to proceed. Given the code name “Have Blue,” its prototype aircraft combined overall shaping, surface faceting, and radar-absorbent materials to minimize detection.

Two Have Blues were built, the first flying in 1977. Over the course of an aggressive test program, both crashed, but together they proved the concept could work, paving the way to the F-117 Nighthawk “stealth fighter.” Though it was about the size of a large fighter, it was actually a bomber with no air-to-air capability.

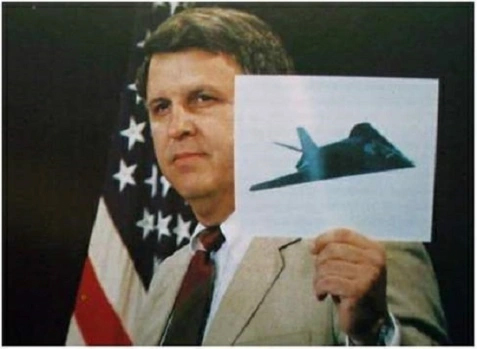

In 1980, then-Defense Secretary Harold Brown revealed the existence of stealth technology to reassure the public that the Carter administration, then fighting for reelection, was diligently prosecuting the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

“By making existing air defense systems essentially ineffective, this [technology] alters the military balance significantly,” Brown told reporters at a press conference. Stealth had the potential to negate Russia’s investment in air defenses.

Brown did not mention how far development had progressed, as those details remained a closely guarded secret.

A year later, the F-117 first flew. Its radar cross section—its apparent size on an adversary radar operator’s screen—has been likened to that of a hummingbird.

Secrets of the Black Jet

Building on the Have Blue foundation, the F-117’s shaping would deflect radar energy, returning only a diminished echo to a searching radar. Its faceted skin was a layer cake of radar-

absorbent materials, the cockpit windows coated with metal to conceal the radar-reflective pilot’s helmet inside. Engine intakes were covered with a radar-deflecting grid, and a flattened and spread-out exhaust was lined with heat-absorbing tiles like those on the space shuttle to minimize its heat signature.

Maintenance was key. The surface of the F-117 had to be painstakingly smooth, and technicians had to spend hours “buttering” caulk and special tape over seams and fastener heads to ensure radar waves couldn’t reflect off those bumps.

There was art in F-117 operations, as well. Pilots developed tactics for countering different types of radar, either approaching head-on, from the side, or at various attitudes to minimize detection. A computer program and database—which the pilots called “Elvira”[a possible nod to the pop culture vampire, “Elvira, Mistress of the Dark”]—cataloged all the known air defense radars in the world and presented the optimum flight profile to fly against each one.

In 1983, just three years after Brown’s disclosure, the F-117 was secretly declared operational, with 14 jets. The Air Force would add 46 more over the next seven years. They were based at Tonopah Test Range, Nev.—far away from curious eyes—and for eight years, flew only at night, on roundabout routes that took them all over the western U.S. Pilots practiced dropping laser-guided bombs with extreme precision and with precise timing.

Stealth pilots were ostensibly based at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., but they commuted to Tonopah on an unremarkable airliner every Sunday night, returning on a Friday night, Goldfein noted. It was tough on their dependents.

“They could never tell their families what they were doing,” he said. “The level of secrecy was so high that if they … ever divulged the secret, the penalty was very severe … it was Manhattan Project-like security.”

In 1988, Pentagon spokesman Dan Howard showed the press a grainy, deliberately misleading photo of the F-117 that distorted its size and shape, confirming the open secret that the Air Force had an operational stealth aircraft, and revealing its designation. The jet would soon be integrated into exercises, and the Air Force was seeking to control the revelations as much as possible. The deceptive photo proved highly effective: Most attempts to deduce the angle of the jets’ wing sweep and the arrangement of the exhausts, for example, were wildly off the mark.

Stealth in Action

The F-117 was first used in combat in 1989, during Operation Just Cause, which ended the regime of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega. A pair of F-117s were used to drop inert rounds into a field near an army barracks, with the intent of making a big bang to generate panic and confusion among Panamanian troops. There was no intent to destroy anything, and Panama had virtually no air defense systems to evade, so the mission was not a true trial of stealth.

At the outset of the program, Goldfein said, Air Force and Lockheed officials “thought they could keep it secret maybe one to two years … maybe.” But the secret held until the official rollout in 1990.

The real test came in January 1991, at the start of Operation Desert Storm, when a U.S.-led international coalition moved to eject Iraqi forces from occupied Kuwait. The F-117 led the assault, targeting command-and-control facilities, suspected nuclear weapons research sites, communications nodes, and other strategic targets.

Iraq’s military was the fourth largest in the world and operated state-of-the-art Russian air defense systems. Then-Maj. Gregory Feest, who would later retire as a major general, recalled that no one could predict for certain whether this “stealth stuff” would work against sophisticated integrated air defense systems, surface to air missiles (SAMs) and antiaircraft artillery (AAA) fire.

“We trusted the engineers,” Feest said in a recent interview. “We were briefed: Here’s your signature against these types of SAMs, here’s your signature against AAA. But you know, we couldn’t verify anything.”

Elvira had “all the IADS,” Feest said. “It would give us the safest route to get around them.”

Some radars wouldn’t be able to see the F-117s, but others could, especially at closer range, Feest said. “Our goal was to just minimize our threat time, when we could be seen and tracked.”

The Iraqis hurled massive AAA into the sky, Feest recalled. The area around his jet was “just so lit up—the biggest fireworks display I’d ever seen,” he said, creating so much light he feared his jet might be visible to the naked eye, and to ground gunners. “I actually thought I was going to get shot down,” he said.

Feest lowered his seat and concentrated on navigating, trying to avoid looking outside. With him was a piece of paper listing all the other F-117 pilots also over Iraq that night. After delivering their munitions, they checked in with the tankers for the return journey hookups. Feest listened carefully and heard every call sign.

“I thought, man, we were lucky,” he said. The F-117s returned unscathed.

“After a couple of missions, we all decided the engineers did a good job,” Feest said, recalling the growing confidence Night Hawk pilots felt as the technology proved itself in battle. “What they told us was true. And we started to feel much better.”

Retired Lt. Gen. David Deptula designed the strategy employing the Nighthawks and selected the targets for the mission. Now Dean of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, he recalls that the 36 F-117s that participated in Operation Desert Storm made up just 2.5 percent of the international air armada amassed to pummel Saddam Hussein’s forces, yet they destroyed 40 percent of the strategic targets.

Lessons Learned

Desert Storm proved stealth worked, confirming Air Force plans to press ahead with developing the F-22, which was by then in the prototype phase. But the operation also revealed the need for new weapons.

An image of a laser-guided GBU-27 bomb going down an air shaft at an Iraqi headquarters became an icon of that war, but such weapons wouldn’t work against targets obscured by clouds, smoke, or dust. In some cases, pilots returned without dropping their bombs, unable to keep the target in sight.

“We needed an all-weather bomb,” Feest said, and the Air Force would soon develop one: the Joint Direct Attack Munition, or JDAM. It was fitted with satellite guidance to precisely reach any aimpoint under any conditions, without the need for pilot updates.

Shortcomings of the F-117 were corrected after the war. For example, it had been designed to only allow one bomb bay door to open at a time, requiring two passes at some targets. This was corrected to allow both doors to open and release weapons simultaneously. Also, pilots remained radio-silent during those initial missions because the antennas had to be retracted for full stealth. Conformal, stealth antennas were added later.

The F-117 was officially unveiled to the public in April 1990, only about three months before Saddam invaded Kuwait. The unveiling ceremony at Nellis was followed by air show appearances to show off the technology. In 1992, soon after the Gulf War, the planes were moved from Tonopah to Holloman Air Force Base, N.M.

“I think it’s the only program in history that had a top-secret program as its cover,” Goldfein added. The F-117 was hidden as part of the Air Force’s “Red Eagles” program which obtained and evaluated Soviet-type aircraft and flew them to learn their strengths and weaknesses.

“That was the cover program. … So if somebody ever saw one, then that was going to be the answer.”

Unwelcome Students

The “Black Jet,” as pilots called it before it received the official nickname “Night Hawk,” next went to war in 1999’s Operation Allied Force, once again aimed at high-value targets in and around Serbia, which also had Russian-built air defenses. This time, it was joined in action by the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber, developed by Northrop starting in 1981.

Lt. Col. Dale Zelko was the first to discover that the Night Hawk was not invincible. On March 27, 1999, just a few days into Allied Force, his F-117 was hit by a Serbian SA-3 missile. He survived ejection and was rescued, but the remains of the jet were collected by Serbia and, presumably, passed on to Russia and China. Stealth secrets were now in adversaries’ hands.

Though Air Force officials continue to be circumspect about exactly what went wrong, the consensus is that the F-117 was hit largely because its flights had become predictable. Serbian forces, abetted by spies near Aviano Air Base, Italy, where the F-117s were based, knew when one took off and could roughly calculate the route it would take. Zelko, said one senior Air Force official, fell victim to a “well-informed guess” about where his airplane would be, and when.

The Air Force had never claimed stealth aircraft were invisible or undetectable, and continued to use the term “low observable”—“LO,” and more recently VLO (Very Low Observable) or ELO (Extremely Low Observable) to describe the technology. Radars and computer processors have grown more powerful over the years, and engineers have had to work hard to stay a step ahead. But the word “stealth” has stuck in the public mind.

John Clark, who headed Lockheed’s Skunk Works from 2022 to 2025 and is now the company’s senior vice president of technology, said it’s likely that Serbia provided Russia and China with samples of the F-117’s technology and materials. But that was hardly a technological windfall, he said.

“I can’t say this decisively, but with what I know, and the involvement that I had, there was nothing that we believe was lost, that compromised the capability of the platform,” Clark said in an interview. “One of the interesting things with the materials … is that it’s more than a simple ‘one-plus-one-equals-two’ recipe. There’s lots of integrated complexities that come with … our LO cocktails and the specific material suites that we put together.”

Reverse-engineering stealth was not as simple as merely determining what was in the radar-absorbent material, Clark noted.

Even having a sample of the final product, it could be “decades to try to come up with the same material,” he said.

Stealth technologies continue to advance. “By the time they actually crack that nut, we’ll have already progressed to the next thing,” Clark said. In fact, by 1999, the early stealth materials used in the F-117 were nearing “the end of their useful life,” he said. “We’d moved on to other stuff.”

In 2011, a Lockheed-built RQ-170 stealth reconnaissance drone crashed in Iran, but its damaged fuselage remained relatively intact. Iran claimed it had shot the aircraft down, then insisted it had reverse-engineered it and unveiled a look-alike aircraft to the press. Clark admitted the downed aircraft, also built by Lockheed, “had later materials” than the F-117, but he said a panel of government and industry specialists concluded that, as with the F-117, it would be very hard for Iran to reverse-engineer the RQ-170.

Phasing Out

After the F-117s were moved from Tonopah to Holloman, pilots were able to lead a more normal family life. Now an open part of the Air Force inventory, it operated there for seven more years. In 2006, with many F-22s in hand and the F-35 on the way, the F-117 era was coming to an end.

Goldfein, then a wing commander at Aviano, got a call from the commander of U.S. Air Forces, Europe, Gen. Tom Hobbins, who gave him his next assignment: We’re going to send you out to Holloman … and your job will be to retire the F-117.

Goldfein was all in, despite the fact that the F-117 was younger than most elements of the Air Force combat inventory.

“I think it was … budget constraints—which always make you have to choose between readiness and modernization,” Goldfein said. Next-generation stealth was coming online, and that “would take us out of the ‘buttering’ business and into the more normalized maintenance business.”

With the F-22 and F-35 in the fleet, retiring the older and maintenance-intensive stealth technology was “an obvious choice,” he said.

Moving from the F-117—designed for rigid attitudes—to the dynamic F-22 posed challenges. The new jet had to perform aircraft-bending high-G maneuvers, which could pull apart seam-filling materials, Clark said. But by then, LO materials science had come a long way.

“Our material suites and the advancements that we made … really dispelled the rumor that the LO was a driving factor at cost for maintenance,” he said. “It was no longer even in the top five.”

Holloman was slated to receive F-22s, and “we needed the hangars” to house them, Goldfein said. That drove the timing. Collaborating with his successor, Brig. Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian, Goldfein worked to make the transition seamless.

But Congress was not fully convinced that the new stealth aircraft were sufficient, and secretly ordered the Air Force to keep its F-117s in “flyable storage,” just in case they were needed for a future war. The aircraft returned to Tonopah, where the wings were removed and stacked beside the fuselages. Goldfein brought in the last one.

Goldfein hesitated a long time before cutting the throttles, he said. “I taxi in, and it’s the first time I’m going to ever shut an aircraft down knowing it would never start again,” he recalled. “And it’s ‘code one,’” or fully capable.

In time, some of them would fly again.

Legacy

Intelligence has shown that “the Soviet Union almost spent themselves into obscurity trying to counter” stealth, Goldfein observed.

The F-117 “probably had as much, if not more impact on that for us during the Cold War as any weapon system on the planet,” he said. Stealth is one of those capabilities that cause “potential adversaries to wake up every morning and decide, ‘not today.’”

“Flyable storage” means that a small cadre of pilots maintain proficiency in the airplane, and occasionally, one is taken out of storage, fueled, lubricated, and flown.

Since at least 2020, Black Jets have taken to the skies, participating in a number of air exercises, such as Red Flag, Air National Guard wargames, and Northern Edge. While the Air Force acknowledges that some F-117s occasionally fly, their mission is not disclosed. Observers speculate that they play the role of stealthy adversaries, but how long they will continue in that role is anyone’s guess.

Future Challenges

The cat-and-mouse advances in stealth and radar technology continue. Rob McHenry, deputy director of DARPA, suggested in June that the “stealth era” will eventually come to a close.

Quantum sensing, “cross-domain sensing,” and artificial intelligence will wear away those advantages as those technologies mature, he said in a visit to AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Quantum sensing seeks to detect extremely small changes in an environment, theoretically making even the stealthiest platform detectable.

DARPA, which focuses on game-changing advanced research, foresees a transition from “quantum sensing as a science to quantum sensing as an engineering discipline,” though exactly how soon that will happen is hard to say.

Mark Lewis, who was the Pentagon’s director of defense research and engineering during the first Trump administration, said stealth is also evolving.

“There was a step change from the SR-71 to the Have Blue and the F-117, and another step change from the F-117 to the F-22,” he said. “And we’ve heard there’s probably another step change to the B-21 and F-47.”

Those advances will continue to enhance aircraft survivability, he said, adding, “I’m gonna go out on a limb and say that stealth is going to be part of many of our major systems for quite some time.”

Stealth is not about being invisible, but rather about making it “more difficult” to detect.

In the early days of stealth, “you could only calculate [radar cross section] for a portion of the airframe,” Lewis said. “And now you can calculate it for the whole thing, and you can make curved shapes where you used to have to do facets. … We’ve also gotten better at building stealthy geometries—things that are stealthy from more angles, right?” Whereas early stealth had to be presented to an enemy radar from a particular orientation, “now we’ve gotten much better at building things that are good from multiple orientations.”

The physics hasn’t “changed all that much” and remains on a continuum, Lewis said.

Artificial intelligence and computing advances do pose a challenge, though, Lewis acknowledged.

“You could easily imagine a machine learning system that is better at detecting hard-to-see objects like stealth aircraft,” he said. “So yeah, it’s going to play a role. … It just means that our adversaries will have better means of detecting these things. But they’ll still be hard to detect.”

Future developments in aircraft design will also play a role in countering advanced detection. The U.S. has experimented with “shape-changing materials now for decades,” Lewis said, technologies that, if producible, would enable “some really interesting things.” He said there are “other interesting things you could do if you could change your surface properties, like reflectivity.”

Several years ago, photographers spotted F-22s and F-35s sporting a variety of highly reflective, silvery surfaces. The Air Force declined to explain those experiments, and Lewis refused to comment now. “I can’t tell you about that for 30 years,” he joked. But the bottom line is, “We’re going to be using stealth for a while.”

There will always be a struggle with what’s called the “burn-through” range, Clark said: the point at which, no matter what countermeasures are employed, enemy sensors will be able to see a stealth platform.

“There are going to be places where the adversary just piles so many things up in that area that, yeah … you’re not going to have overflight of those specific areas, but those areas are still going to be relatively small,” Clark said.

Stealth will remain part of the Air Force’s tool kit for years to come, Goldfein said.

“In most of the countries on the planet, if you were to paint … a little heat map [of air defenses], we’re still pretty viable,” he said. “And then, project out 10, 15, 20 years. Guess what? Most of the planet is going to stay about the same. So stealth is always going to be really, critically important, but it’ll be combined with other technologies that not only make it better, but make the other technologies better.”

Clark said critics like to say they can find a stealth aircraft, but “they can only find the stealth aircraft in a specific spectrum … when they already know where it is and they can stare the sensor at it.” It’s like a needle in a haystack, he said.

“If I’m sitting in the haystack and somebody drops the needle on my lap, I can find the needle. But if the needle is in the middle of the haystack, there’s no way you’re actually going to find it, even though it’s in there.”

To stop a low-observable aircraft from achieving its objective, Clark said, “You have to detect, and you have to track, then you have to engage before you can kill.” If all the sensor operator sees is “an intermittent detect, and you see it for three seconds out of a 30-minute window, that’s not useful.”

While the F-117 may be all but a memory, stealth and its challenges remain.