The Air Force’s Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile is delayed and may significantly overrun its expected cost, which could partially explain why the service is reviving the hypersonic AGM-183 Air-Launched Rapid-Response Weapon.

The Government Accountability Office, in its annual report to Congress on the status of various major defense programs, said last week that the HACM is “behind schedule,” though the Air Force is working with prime contractor Raytheon and engine supplier Northrop Grumman to field the weapon on time.

The service and the contractors are working to “develop a new schedule baseline that still adheres to the 5-year time frame for rapid prototyping efforts,” which calls for initial fielding of HACM around 2027.

Raytheon, a division of RTX, is “projecting that it will significantly exceed its cost baseline” for HACM, the GAO reported. The Air Force is considering dropping two flight tests as a cost-saving measure to get spending back on track, the watchdog agency said.

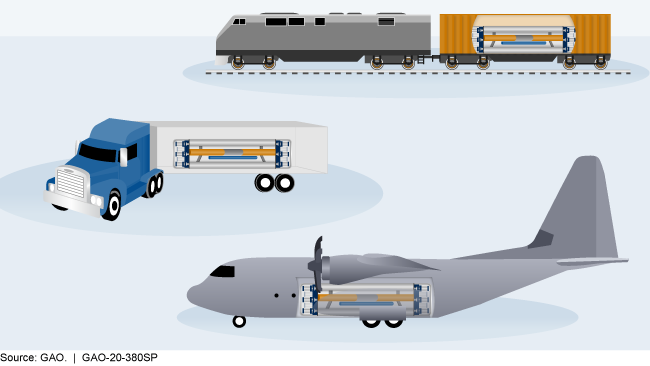

HACM, the Air Force’s preferred hypersonic missile, is envisioned as a weapon small enough to be carried by F-15 or other fighters and able to travel at five times the speed of sound. The HACM vehicle is propelled to hypersonic speed by a booster that separates from the main weapon; the vehicle then ignites an air-breathing engine that powers it to its target.

“The Air Force plans to build 13 missiles during the rapid prototyping effort,” the GAO said, “including test assets, spares, and rounds for initial operational capability.”

The service expects to start rapidly fielding missiles in fiscal 2027 before tweaking its design ahead of full production, “based on global power competition and urgency” to address threats, GAO said. A decision to begin full production would come in 2029, the Air Force told the watchdog agency.

In April, the Air Force declined to comment when asked if the HACM would fly for the first time in the first quarter of 2025 as planned. A service spokesperson told Air & Space Forces Magazine at the time that the service would begin withholding information on its hypersonics programs for security reasons. A Raytheon spokesperson directed all inquiries to the Air Force.

The HACM is one of several hypersonic design initiatives underway within the Air Force. Lockheed Martin tried to develop the AGM-183 ARRW in a rapid maturation effort that yielded mixed results in testing. Though the last few tests, which mimicked operational flight, were generally satisfactory, the service paused funding for the effort in its fiscal 2025 budget.

The Air Force said hoped to continue research and development using data acquired from the program, but Andrew Hunter, the service’s former acquisition boss, told the House Armed Services Committee’s tactical air and land forces panel in 2023 that the Air Force did not “intend to pursue follow-on procurement of the ARRW once the prototyping program concludes.” A senior service official later reported the ARRW was “officially dead.”

That seems to have changed, however. Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin told House lawmakers on June 5 that the service’s fiscal 2026 budget request will include two different hypersonic weapon programs. That includes ARRW, a “larger form factor [missile] that is more strategic, long-range, that we have already tested several times,” he said.

Allvin said the Air Force is accelerating ARRW’s development as well as procurement.

In the same hearing, Air Force Secretary Troy Meink said the Air Force is determined not to buy a token number of hypersonic missiles. “We’ve got to be able to buy more than 10,” he said, adding that the Air Force has “a big focus” on achieving scale and low cost for the weapons.

Unlike the HACM, ARRW is a large weapon that will be carried solely on a B-52 bomber’s wing pylons. The booster—borrowed from an Army Tactical Missile System rocket—propels the warhead to hypersonic speed, after which it glides to its target. The Air Force prefers the HACM, though, because it is smaller, more maneuverable and longer-range because of its air-breathing engine. The weapon may also be carried by a broader range of fighters and bombers in the future.

A former senior defense official argues it makes sense to keep ARRW going because the HACM’s delays are “just what you would expect with a cutting-edge technology.”

“It’s generally a good idea to have an alternative,” he said.

Even if HACM works out, he added, then the Air Force has two options instead of becoming dependent on a single one. “We will learn a lot from continuing to fly ARRW,” he said, and that learning can shape other hypersonics programs.

Raytheon has received about $1.4 billion from the Air Force for the HACM program so far. The missile began as a middle-tier acquisition program, which can move faster than typical procurement, but will likely become a more traditional major defense acquisition program at some point.

The GAO said HACM’s preliminary design review, slated for March 2024, was postponed by six months because “the program needed more time to finalize the hardware design.” Quoting Air Force officials, the GAO said “another review, scheduled for 2025, would validate the fully operational configuration for use in the final flight tests.”

“Program officials said that the delays will reduce the number of flight tests the program can conduct during the 5-year rapid prototyping effort from seven to five,” the watchdog added.

Even with five test flights instead of seven, the Air Force told the GAO “that the program will still be able to establish sufficient confidence in the missile to declare it operational and to meet all the [rapid acquisition] objectives.”

The HACM program “is prioritizing capabilities that can be fielded quickly,” GAO said The Air Force is deciding which capabilities it wants in a minimum viable product, and will set those criteria in the missile’s final design review this year.

As part of that process, the HACM program is soliciting operator feedback on the missile’s design and tracking digital information for “every part with a serial number,” GAO said. Raytheon can then assemble the digital components into a model that can be tested in simulations.

The program told GAO that it has “revised its transition strategy to align with Air Force goals for having a larger inventory of missiles sooner, while simultaneously improving the manufacturability of the design and expanding the capacity of the industrial base,” the report said.