Days before the New START Treaty is set to expire, experts, lawmakers, and former defense officials have varied perspectives on how President Donald Trump’s administration should proceed as it considers future arms control agreements with nuclear weapon states.

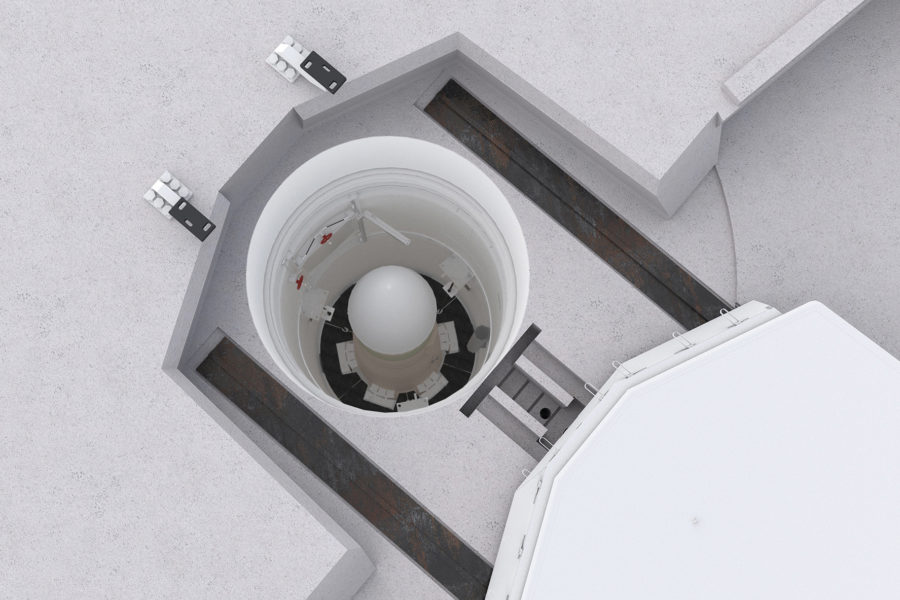

The U.S. and Russia implemented the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty in 2011, agreeing to limitations on their inventories of ground-based and submarine-launched ballistic missiles and nuclear-armed bombers. The original treaty was extended for five years in 2021 under President Joe Biden, but the agreement is now slated to dissolve Feb. 5 with no extension or alternative to take its place.

The Russian Federation in September offered to extend the treaty another year, but the Trump administration hasn’t formally responded to the proposal, which would retain current limits but without verification measures included in the original agreement and which Russia has not complied with since 2023. Trump has said he’s interested in a new treaty, but with a broader scope that includes other strategic weapons and adds China as a signatory.

Arms control advocates are concerned the treaty’s lapse could lead to a new arms race between the U.S. and Russia. Rose Gottemoeller, the lead negotiator for New START, said that despite Russia’s non-compliance, the agreement has given the U.S. important insight into Moscow’s nuclear arsenal and has constrained production to the established limits—1,550 deployed warheads, 700 delivery vehicles, and 800 launchers. While she agrees with Trump’s argument for a new, more expansive treaty, Gottemoeller told members of Congress during a Feb. 3 hearing she’s worried that without an agreement in place, Russia will rapidly increase, or “upload,” its inventories once New START expires.

“A one-year extension would not prejudice any of the vital steps that the United States is taking to respond to the China nuclear build-up,” Gottemoeller told the Senate Armed Services Committee. “The period will buy extra time for preparation without the added challenge of a Russian Federation, newly released from New START limitations, embarking on a rapid upload campaign. This would not be in the U.S. interest.”

Other experts, however, argue that Russia’s violation of New START’s verification mandates—which require in-person inspections and data sharing between the two countries—limit the value of the treaty. Former U.S. Strategic Command Commander Adm. Charles Richard said he wouldn’t recommend extending New START without those procedures as part of the deal.

Richard said during the hearing that extending the current treaty doesn’t place the same constraints on the U.S. as it does on Russia. And without verification measures, it increases uncertainty.

“Arms control, if done correctly, enhances strategic deterrence, enhances certainty, enhances confidence,” Richard said. “But it has to include all parties, it has to include all weapons, and it has to have verification mechanisms built in with consequences for noncompliance.”

Timothy Morrison, who served as a deputy assistant to the president for national security affairs during Trump’s first administration, said the end of New START presents a “blank slate” opportunity for the U.S. to rethink its approach to arms control. That includes questions around how to enforce compliance and whether the treaty should cover novel weapons, like the Fractional Orbital Bombardment Systems that Russia and China have both demonstrated.

During a Center for Strategic and International Studies event the same day, Tom Karako, director of the center’s Missile Defense Project, said that while the end of New START may usher in a “new era” of arms control, the U.S. hasn’t yet figured out what this next phase should look like.

“Before we’re going to enter a new area, I would say we’re going to enter a wilderness, and we have to figure out what it is that we want to cut up or put a fence around,” he said. “I think we need to let it lapse, let it expire, and then truly take a fresh look at the world.”

Allied Posture

The potential collapse of “negotiated restraint” through a nuclear arms treaty comes as the U.S. is calling on its longstanding allies to play a larger role in their own defense, Gottemoeller noted, raising questions, particularly in Europe, about whether these countries should develop their own nuclear deterrent.

“It is, in my view, raising a lot of questions among our allies,” she said. “There is no active announcement from any NATO ally, but there are many debates and discussions that have surprised us among our NATO allies.”

Even “friendly proliferation” is a concern, Gottemoeller said. Richard agreed, but said the motivation for allies to build more nuclear weapons, in his experience, is less about the status of arms treaties and more about the strength of U.S. capabilities.

“In my conversations with allies, the issue was less about treaties and it was more about capability and will,” he said. “And we have recently demonstrated will. I think we’ve made positive movement in that direction. But it’s the capabilities we don’t have that are a much bigger concern to our allies in terms of our ability to honor our extended deterrence commitments.”

Golden Dome

As China builds up its nuclear arsenal and Russia pursues more novel tactical weapons, the U.S. over the last year has increased its focus on defensive capabilities. The development of Golden Dome, an advanced missile defense shield, has become a top priority for the Pentagon under the second Trump administration.

During the Senate hearing, Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), said he’s worried the project could “undermine mutual deterrence” and offers “a false sense of security.” The goal of intercepting full salvos of ICBMs is unrealistic, he said, and the cost of developing space-based missile could prove “unworkable.”

The Trump administration has said it expects Golden Dome to cost $175 billion to demonstrate an initial capability over the next three years, though outside experts have said it could cost more than $1 trillion over time to build out the architecture with the space-based interceptors that would be needed to protect against missile threats.

Morrison noted that it’s possible the Pentagon’s pursuit of Golden Dome could serve as a means to get Russia and China to negotiate a new treaty, arguing that the original START Treaty of the 1980s was negotiated against the backdrop of the Reagan administration’s Strategic Defense Initiative, nicknamed “Star Wars,” an earlier space-based missile defense effort. Ultimately, the U.S. abandoned the program.

“From the perspective of what our adversaries think about this, is it a worthwhile investment to pursue and a worthwhile strategy to pursue to get Russia and China to come to the table out of fear that we may actually be able to build it?” he said. “I wonder if we would have had START 1 if we hadn’t had Star Wars.”