While China and Russia have ramped up testing of advanced space weaponry in recent years and observers call for the U.S. to develop more offensive capabilities of its own, senior Pentagon officials at the recent Aspen Security Forum highlighted the fine line America faces in preparing for a potential conflict in orbit.

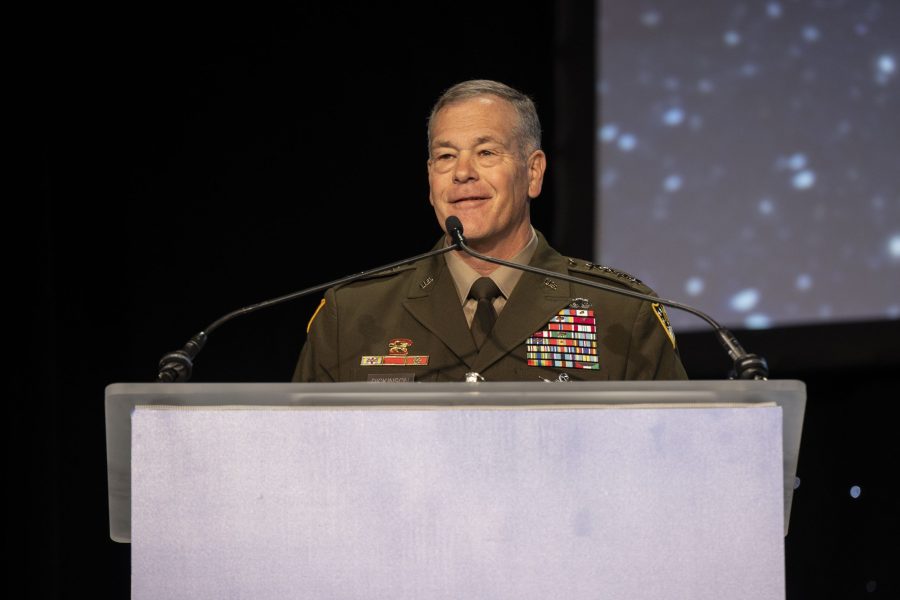

On one hand, the threats are growing more and more pronounced, as U.S. Space Command boss Gen. James H. Dickinson acknowledged in Aspen last week.

In December 2021, for instance, a new Chinese Shijian-21 “space debris mitigation satellite” grappled with a defunct Chinese navigation satellite, transported it from low-Earth orbit to a distant “graveyard belt,” and then returned to geostationary orbit—an ability that could threaten U.S. satellites.

Around the same time, China tested a Fractional Orbital Bombardment System (FOBS)—a nuclear-capable hypersonic glide vehicle that traversed the globe and revealed the potential to evade not only U.S. missile defenses, but also satellite early warning capabilities.

Russia, meanwhile, tested a direct-ascent anti-satellite missile in November 2021, destroying one of its own satellites and creating a massive 1,500-piece debris field. And a year earlier, Moscow demonstrated its “nesting doll” Kosmos-2542 satellite, which released a sub-satellite that reportedly stalked a U.S. spy satellite in low-Earth orbit, and then released another sub-satellite that officials believe was likely an anti-satellite weapon.

“As we look across the space domain, it’s important to understand that we’ve got some competitors out there that are developing and demonstrating capabilities that should cause us concern,” Dickinson said. “Whether it’s directed energy weapons [lasers, microwaves or particle beams], or direct ascent ASAT [anti-satellite missiles], or China’s SJ-21 [dual-use satellite], those kinds of capabilities are something we need to be concerned about.”

Such threats have led some experts like retired Col. Charles Galbreath, senior resident fellow at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, to advocate for the Space Force and U.S. Space Command to develop more offensive counterspace weapons of its own to deter China and Russia from using their growing arsenals.

“It’s oxymoronic to establish a new military service charged with protecting interests in space without arming it with the weapons it must have to accomplish that mission,” Galbreath wrote in a research paper released in June.

Yet the long-term effects of any actions in space, where debris can linger for decades, loom over any such discussions. The U.S., while standing up the Space Force and reactivating SPACECOM, has also been a key proponent for establishing internationally accepted rules in order to normalize space operations and is a signatory to the Artemis Accords designed to bolster peaceful exploration of space—as well as the venerable Outer Space Treaty banning nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in space.

“The United States intends to continue to be the world’s responsible leader in space, and that includes the U.S. military,” said John Plumb, assistant secretary of defense for space policy at the Aspen Forum. “It’s in the interest of all spacefaring nations and private companies to have a safe, secure and stable space domain, and that means minimizing space debris as part of our normal operations, and making sure we have ways to remove debris if things go wrong. And any military operations include that consideration.”

The tension between maintaining a space domain critical to both U.S. military operations and the global economy and countering the aggressive development of offensive space weapons by China and Russia, has led SPACECOM to emphasize nonkinetic responses.

While much of U.S. Space Command and Space Force acquisition remains classified, U.S. officials have acknowledged that there are “hard kill and soft kill” space programs funded. There are also offensive counterspace capabilities that don’t involve debris-producing kinetic action, to include jamming, directed-energy lasers, cyber attacks, and Special Forces targeting of satellite ground stations and communications links.

“I don’t publicly speak about offensive capabilities, because I don’t think that would be appropriate, but I will say that an [adversary’s] activity that happens in space may not receive a response in space,” Dickinson said. “At U.S. Space Command, we think about leveraging our capabilities in all domains, including land, air, sea, and cyber. We have conducted countless exercises with other combatant commands working on how we approach this problem. And we are at a point where I can say today that we’re ready.”

Meanwhile, officials have also focused on leveraging increasing commercial space launch capabilities to field mega-constellations of smaller military satellites, thus building a more resilient and redundant footprint in space and complicating an adversaries’ targeting actions.

“We’re focusing on making U.S. space assets more resilient, so there is no Pearl Harbor in an adversary’s first punch,” said Salvatore ‘Tory’ Bruno, CEO of United Launch Alliance. “That means we can take a hit and keep on going, or position an asset so it is less accessible to the weapons adversaries are developing.”