How the Air Force Cleared the Way for Delta Force.

The daring raid on Caracas, Venezuela, to snatch and grab Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro may have been characterized by Secretary of State Marco Rubio as a law enforcement operation, but it had all the trappings of a high-stakes military operation when the surprise incursion was launched in the wee hours of Jan. 3.

More than 150 aircraft—including bombers, fighters, intelligence, reconnaissance, surveillance, and helicopters—participated in “Operation Absolute Resolve,” Air Force Gen. Dan Caine, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters the morning after.

B-1B Lancer bombers; F-22 Raptor, F-35 Lighting II, and F/A-18 Super Hornet fighters; EA-18 Growler electronic attack planes; E-2 Hawkeye early warning aircraft; numerous intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance aircraft; and untold drones were all airborne in support missions, as helicopters from the Army’s elite 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment descended on Maduro’s location.

“As the force began to approach Caracas, the Joint Air Component began dismantling and disabling the air defense systems in Venezuela, employing weapons to ensure the safe passage of the helicopters into the target area,” Caine told reporters in a joint press conference with President Trump, Secretary of State Marco Rubio, and Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth at the president’s Mar-a-Lago residence in Florida.

“The goal of our air component is, was, and always will be, to protect the helicopters and the ground force and get them to the target and get them home,” Caine added.

U.S. Space Command, U.S. Cyber Command, and intelligence agencies, including the CIA, NSA, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, participated in the effort, Caine said. The mission included knocking out electricity in the capital.

The 160th flew in Delta Force special operators along with federal law enforcement personnel at an altitude of just 100 feet, skimming the water and the cityscape before reaching Maduro’s well-defended compound at 1:01 a.m. Eastern time. Coming under fire, one helicopter was struck as was its pilot, who sustained at least two injuries, but managed to maintain control and complete the mission. Dozens of Venezuelan and Cuban protective forces were killed, but the U.S. forces suffered no such losses.

Among the weapons deployed was one President Trump would refer to later in January, in an interview with the New York Post, as “the ‘discombobulator’ weapon.”

“I’m not allowed to talk about it,” he said in the interview with the Post. “They had Russian and Chinese rockets, and they never got one off. We came in, they pressed buttons and nothing worked. They were all set for us.”

Whether that was a sonic weapon or something else remains unclear and unproven.

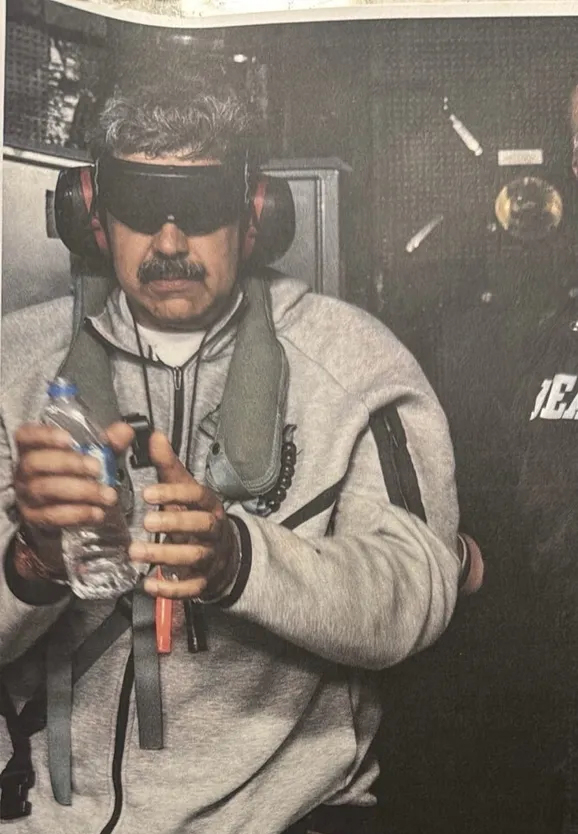

What is clear is that by 3:29 a.m. Eastern time, Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, were embarked aboard the USS Iwo Jima amphibious assault ship, and would soon be taken to New York to stand trial for drug trafficking and related charges.

Poor weather delayed the operation over a period of days, but “last night, the weather broke just enough, clearing a path that only the most skilled aviators in the world could maneuver through—ocean, mountain, low cloud ceilings,” Caine said.

The role of airpower was critical to the operation’s success. Mark Montgomery, a retired Navy rear admiral and senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, said the “airstrikes on military targets serve two purposes: to create the space for Special Forces to conduct their capture operation, and to signal to the Venezuelan military that ‘this is not a fight you want to take up.’”

The capture of Maduro on a moonlit night created a power vacuum in Venezuela, which Trump said the U.S. would fill until there is a “proper transition” to a new Venezuelan leadership.

Trump acknowledged the U.S. operation was risky. “This is an attack that could have gone very, very badly,” Trump said. “We could have lost a lot of people last night. We could have lost a lot of dignity. We could have lost a lot of equipment.”

Instead, the operation went off almost without a hitch, even as a “second wave” of forces stood by in case of trouble. “We’re ready to go again if we had to,” he added.

The U.S. forces deployed for the operation included 12 F-22s from Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va. Publicly available imagery shows Air Force F-22s are on site at Roosevelt Roads Naval Station, Puerto Rico, alongside the Vermont Air National Guard F-35As—a unit that specializes in suppression of enemy air defenses—U.S. Marine Corps F-35Bs, and other U.S. military aircraft.

During the buildup of military forces in the region, the U.S. also used air bases elsewhere in Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, and El Salvador, among other locations, and Navy aircraft operated from the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford and the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima, as well as bases in the continental U.S.

The B-1 bombers appeared to have originated from Dyess Air Force Base, Texas, according to open-source analysis. Both F-22s and B-1s have flown south from their home bases in the U.S. in recent days, civilian flight trackers have observed. Those operations could have been a rehearsal mission, decoys, or even the start of operations that were later called off.

An RQ-170 Sentinel, a stealthy, flying-wing surveillance drone, was also spotted over Venezuela in videos posted on social media. Caine said U.S. aircraft deployed from 20 different locations in the Western Hemisphere on land and at sea during the operation to capture Maduro.

Neither the Air Force nor U.S. Southern Command would comment on operational movements and activities, so the RQ-170’s participation in Operation Absolute Resolve remains officially unconfirmed. But experts interviewed by Air & Space Forces Magazine expressed no surprise that the unmanned aircraft had popped up near the Venezuela operation because it is well suited for a key component to the mission: stealthy intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

In Caine’s debrief, he described the “months” of intelligence work that went into preparing for the operation, using a range of assets to monitor Maduro and “understand how he moved, where he lived, where he traveled, what he ate, what he wore, what were his pets.”

Airborne intelligence in well-defended downtown Caracas required a delicate touch. The Air Force’s best-known ISR asset, the MQ-9 Reaper, lacks the stealth needed to evade Venezuela’s relatively advanced air defenses, which include Russian S300 integrated air defense systems.

“You cannot park an MQ-9 over the capital of Venezuela and expect that thing to survive,” said retired Brig. Gen. Houston Cantwell, a senior fellow at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, who commanded the 732nd Operations Group and its RQ-170s for two years in the mid-2010s. “But an RQ-170 has a much better potential to be able to surveil when there is an integrated air defense system that is also over the same piece of sky.”

Besides simply surviving, the RQ-170’s stealth makes it harder for those being surveilled to be aware of what’s happening, noted veteran aviation reporter and aerospace analyst Bill Sweetman. “You might want to remain covert so people don’t take precautions against being observed,” he noted.

Airborne ISR complements space-based satellite ISR, Cantwell said. “You’ll see the adversary change their patterns of life, because you can’t change the revisit rate of a satellite. … And so they’ll either hide capabilities or stop doing certain kinds of activities, knowing that space is going to be there,” Cantwell said. “But when you throw in something like a 170, now there’s an uncertainty. Now you can fill in some of the gaps that exist with space and allow a capability to revisit a target in an unpredictable manner.”

Flying closer to the Earth’s surface, air-based assets also provide different angles and can collect different kinds of signals, Cantwell added, making them useful for “battle damage assessment, as well as that battlefield preparation in advance.”

In one of the few public disclosures about the RQ-170, the Air Force described an exercise at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., in 2020 during which a Sentinel drone flew alongside many of the same platforms that would be used five years later to strike Venezuela, such as F-22s, F-35s, and Navy E/A-18 electronic warfare jets. The main objective was to test whether the F-35 could suppress enemy air defenses so platforms like the RQ-170 could penetrate contested airspace. This may have been the case in the Venezuela operation.

Shrouded in Secrecy

First spotted by reporters at Kandahar Airfield in Afghanistan in the mid-to-late 2000s, the RQ-170 has always been shrouded in mystery, with the Air Force releasing precious few details about its capabilities and movements. Sweetman, one of the journalists who first reported on the RQ-170’s existence, dubbed it the “Beast of Kandahar,” a nickname that stuck, particularly after Iran captured one in 2011.

Years later, he and others have been able to surmise a few things about the drone. “From the size of it, it looks as if you’d carry perhaps one, or at most two payloads on it,” Sweetman said. “The one that’s been seen most has been electro-optical, but I wouldn’t be surprised if you could swap that out for a radar. It’s not very big. It doesn’t have a lot of payload volume. So it’s not the sort of thing that would be a multisensor payload, I think. It’s certainly not new … and probably quite modest in range and altitude.”

Over the past two decades or so, RQ-170s have reportedly been spotted flying near North Korea and Iran, but Cantwell said the aircraft are far more active than most people realize.

“The RQ-170 has been used constantly in multiple combatant commands since its inception,” he said. “You just never hear about it because it is such a highly classified capability.”

While much remains unconfirmed or unknown about the RQ-170, it is not entirely an enigma. The Air Force has acknowledged its existence and published at least one photo of it, and in 2011 Iran was able to seize control of one flying over the Middle East, putting it on display for the world to see.

Indeed, Sweetman noted that the service has capabilities that are even more secret and high-tech. In 2014, he reported on the existence of an RQ-180 drone—something the Air Force later briefly confirmed but has since said nothing about.

The Venezuela mission and the intelligence Caine referenced shows what specialized ISR can bring to the fight, Cantwell said.

“The value of stealthy ISR is so important, and it’s been demonstrated time and time again,” he said. “Whenever you have a high-value operation going on, the more intelligence you can have, both in advance and during the actual operation, the better chance you have of success. So these stealthy, penetrating ISR platforms really prove their worth during these real-world operations. It really shows that in the future, we have to continue to invest in this kind of penetrating ISR if we want to maintain that advantage in the future.”