Four satellite missions will launch in the coming year to demonstrate on-orbit refueling, servicing, and repair capabilities to extend the lives of military satellites. Funded by different Department of Defense entities, each will also entail commercial efforts.

The missions are critical for the Space Force, according to officials and industry executives, which sees dynamic space operations—the ability to maneuver satellites as needed to either approach or avoid adversary space systems—as crucial to its ability to fight and win a space conflict. Without that ability, every maneuver that expends a satellite’s fuel effectively shortens its life.

China, which operates a smaller space fleet, appears a step ahead in this regard. In June, two Chinese satellites docked in geosynchronous Earth orbit, performing the first-ever on-orbit refueling mission in GEO. The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency demonstrated on-orbit years ago with satellites in low-Earth orbit and special refueling equipment in 2007. But standards for refueling satellites have changed little since then.

The Space Force is betting the private sector can provide these capabilities, and all four missions scheduled for 2026 aim to demonstrate not just the technology but the business case, as well.

The four planned operations will all be in GEO, more than 22,000 miles above the earth’s surface. Operating from a fixed point in the sky relative to the ground, GEO offers consistent communications and coverage, with more than 500 high-end, large satellites performing crucial telecommunications and broadcasting functions. These highly engineered spacecraft, developed at great expense and intended to have a useful life measured in decades for both government and commercial customers, are prime opportunities for life-extending services.

Rob Hauge, president of SpaceLogistics, a Northrop Grumman company, said the opportunity is huge. “Every year about 10 to 20 reach their end of life because they run out of fuel,” he said.

Without having been designed to take on additional fuel in flight, the question becomes how to retrofit that capability to an existing system. One solution: Add a new component to the existing satellite bus, a so-called “Mission Extension Pod.”

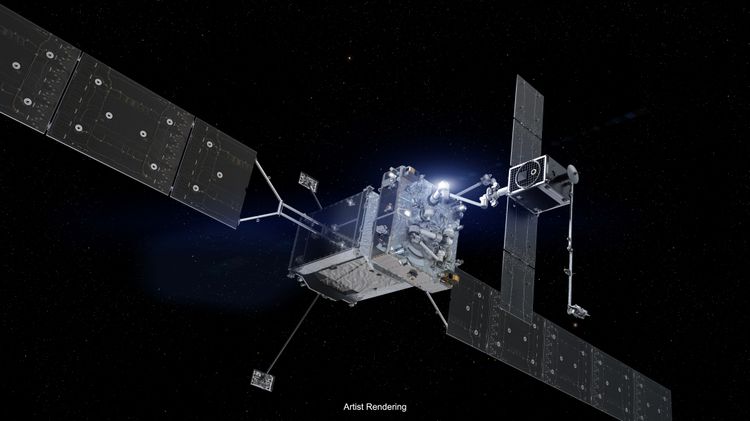

SpaceLogstics has developed its own Mission Robotic Vehicle to bridge service satellites in GEO. Equipped with an autonomous robot arm developed by the Naval Research Laboratory, and funded with DARPA money, Space Logistics will launch an MRV next year to demonstrate Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS). Under that program, MRV will recover a satellite and reposition it in orbit, and then, using its robotic arm, capture and install a Mission Extension Pod, attaching it to the existing satellite and giving the satellite a new lease on life, with freedom to maneuver.

Hauge said once in space, the MRV can “do that again and again and again,” extending the profitable life of aging satellites.

The MRV can also be used for “anomaly resolution,” said James Shoemaker, DARPA program manager for RSGS. In other words: it can repair systems.

About three times a year, something unknown goes wrong with a satellite in GEO, Shoemaker said. “You’ll have a partial deployment of a solar array where, perhaps the hinge just gets a little stuck,” or an antenna deployment doesn’t go as planned, he said. Operators on the ground can try various measures to resolve the problem, but as they “try to rock the satellite” to shake a stuck part loose, they also are expending some of its limited fuel.

Often, when something goes wrong, operators are basically in the dark, Shoemaker said. MRV can maneuver near the satellite to provide “a picture and a close inspection of what exactly is wrong,” making it “a lot easier for them to figure out a solution.”

It’s notable, Shoemaker said, that RSGS is the second DARPA program to demonstrate on-orbit refueling and servicing capabilities.

“Typically, DARPA does things first to prove you can do them, and then we hand them off and start doing something different,” he told Air & Space Forces Magazine. Revisiting a challenge is “somewhat unusual,” he said, but the earlier Orbital Express in 2007 was in LEO, where the economics of servicing and repair are very different. Satellites in LEO are typically smaller and less costly, making repair not necessarily worth the cost.

In GEO, where satellites operate in a single orbital plane above the equator, the satellites are larger and more costly, with much wider areas of coverage. And in GEO, Shoemaker explained, “changing your angle of inclination takes a lot of delta V, a lot of fuel.”

Greg Richardson, executive director of the Consortium for Space Mobility and In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing Capabilities, or COSMIC, a professional association that works to promote on-orbit capabilities, said the economics of on-orbit servicing just don’t add up in LEO.

So while 2007’s Orbital Express “was a great demonstration of technology—it showed what’s possible,” he said, “if we’re going to make on-orbit refueling routine, reliable, and safe, the primary place where that’s going to happen is where there are lots of clients: in the GEO orbit.”

In GEO, “refueling infrastructure can support many clients … and that’s the key to bringing down costs,” Richardson said.

Essentially, he sees solutions like MRV and MEPs as akin to the economics of a gas station compared to having to build out your own fueling infrastructure outside your home. “When you go and fill up, you don’t have to buy an entire gas station to fill up your car,” he explained. “You buy the gas that you need, and some fraction of that cost pays the overhead and fixed costs. … That’s what you want to do in orbit.”

The COSMIC community, which brings together representatives from government, industry, and academia, sees on-orbit refueling of satellites in GEO as the most commercially viable use case.

But the Pentagon is not limiting its research and development to that one regime. Its other three satellite mission-extending operations next year include:

- Astroscale U.S. Refueler. A commercial refueling satellite developed by the U.S. subsidiary of Tokyo-based Astroscale Holdings, this program is funded by the Space Force’s Space Systems Command. Scheduled to launch next summer, it will conduct the U.S.’s first-ever hydrazine refueling operation in GEO, refueling a U.S. military satellite on orbit.

- Tetra-5. A Space Force partnership with the Air Force Research Laboratory, this program aims to demonstrate autonomous Rendezvous, Proximity Operations and Docking along with an on-orbit inspection and refueling operation.

- Kamino. Funded through the Defense Innovation Unit, this effort will put a satellite system on orbit carrying hydrazine fuel intended for transfer and delivery to refuel other satellites in GEO.