In its 75-year history, 22 Airmen have led the Air Force as Chief of Staff. Each came to the post shaped by the experiences—and sometimes scar tissue—developed over three decades of service. Each inherited an Air Force formed by the decisions of those who came before, who bequeathed to posterity the results of decisions and compromises made over the course of their time in office. Each left his own unique stamp on the institution. As part of Air Force Magazine’s commemoration of the Air Force’s 75th anniversary, Sept. 18, 2022, we set out to interview all of the living former Chiefs of Staff, ultimately interviewing Chiefs from 1990 to the present.

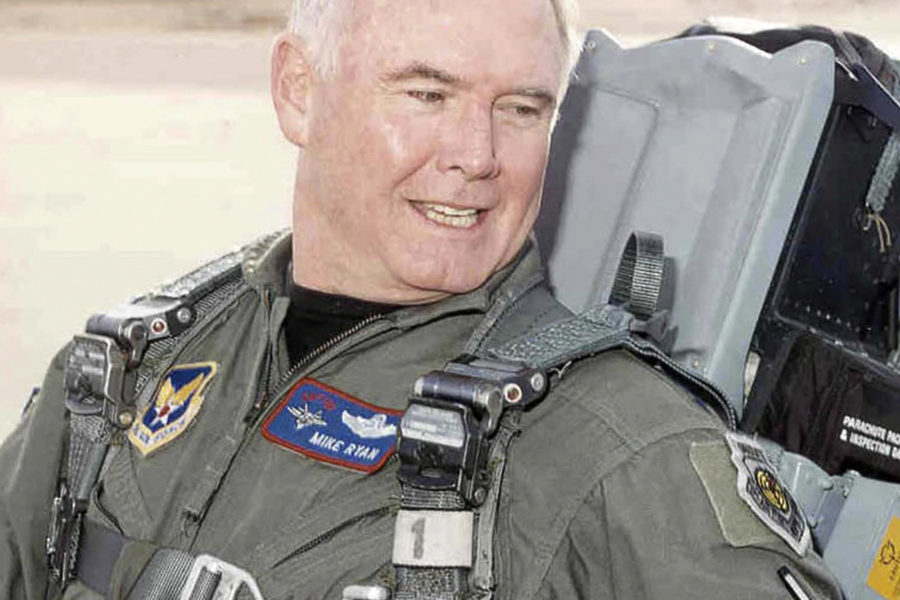

Gen. Michael E. Ryan, CSAF No. 16 (1997-2001)

As America rolled toward the end of the second millennium and the year 2000—Y2K, as it was dubbed—President Bill Clinton was in his second four-year term as President, Rep. Newt Gingrich was in his second two-year term as Speaker of the House, and the Defense Department was in trouble. Eight years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Americans were more interested in the new “dot-com” boom than national defense. The post-Cold War drawdown that began in 1991 had twisted military personnel policy such that it seemed the armed forces were more focused on getting people out of uniform than in recruiting members to join or stay in.

The Air Force suffered a 20 percent cut in the six years from 1991 to 1997, a loss of $18.3 billion a year. The fighter force shed 1,800 jets in that time, a 40 percent reduction since 1987. The missions, however, continued: Somalia in 1992, Haiti in 1994, Bosnia in 1995, not to mention Operations Northern and Southern Watch, no-fly-zone enforcement over northern and southern Iraq, which demanded continuous U.S. Air Force presence.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Ronald R. Fogleman, nearly three years into his own four-year tour, was in a bind. He believed the cuts to the Air Force were dangerous to U.S. national security, but couldn’t seem to convince the people who mattered—in particular, Defense Secretary William S. Cohen—that he was not some Chicken Little warning that the sky was falling. Worse, he was also butting heads with Cohen over personnel matters in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on Khobar Towers, a military housing complex in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, where a truck bombing in 1996 had killed 19 U.S. Airmen and wounded 400 American and allied military and civilian personnel.

Congress and the public wanted accountability, and Cohen, a former Republican senator from Maine who had crossed party lines to join the Clinton administration, was willing to pin the blame on the one-star commander on the scene, Brig. Gen. Terryl Schwalier. Fogleman was not. In July 1997, Fogleman elected to retire early. “My stock in trade after 34 years of service is my military judgment and advice,” Fogleman wrote to Airmen that July 30. Now, he wrote, “I may be out of step with the times and some of the thinking of the establishment.”

Enter Gen. Michael E. Ryan. While not a stranger to Washington—Ryan had been a military assistant to Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Larry Welch (CSAF No. 12) and for two Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Generals Colin Powell and John Shalikashvili—but he was returning after three and a half years in Europe, during which he had led the U.S. air campaign that forced an end to the Bosnian civil war and led to the Dayton Peace Accords.

In Bosnia, Ryan had been left largely to his own devices. “No one told me what to do. No one told me to put a work plan together called [Operation] Deliberate Force,” he said. “I just did that on my own. No one tasked me to do that. And I picked every … aimpoint that we used in that war to avoid civilian casualties because we couldn’t be seen as being as bloodthirsty and as committing atrocities, as the participants in that war had been [doing] to each other. In Srebrenica, they killed maybe 6,000 Muslims. There was a horrible war. And how do you stop a war? How do you end a war? We were able to do it by taking away the Bosnian Serbs’ capability to fight.”

Bosnia, Ryan said, was his greatest legacy. But he himself had descended from a unique Air Force legacy, having spent his entire life within the bubble of the Air Force as the son of a decorated bomber pilot, Gen. John D. Ryan (CSAF No. 7). The elder Ryan became Chief in 1969 when Mike was a young captain flying F-4s at Holloman Air Force Base, N.M.

Now for the first and only time in the history of the U.S. armed forces, the son of a former service chief had advanced to reach the same position. What he inherited, though, was an Air Force in crisis.

“I found my Air Force in free fall,” Ryan said in a recent interview. “There was no safety net. We didn’t have a stopgap. There was nothing that was going to keep it from continuing to fall. We had become victims of our own success, in a way: We had gone and done the Gulf War, we had done Bosnia, touted as the war that was won by air alone.”

In the wake of those conflicts, American air power was so overwhelmingly powerful and effective, its technology so obviously superior, the nation was taking that capability for granted.

“We were faced with, ‘where’s the peace dividend here?’ And ‘where’s the threat for the future?’”

That future looked busy to Ryan. Southern Europe, where the former Yugoslavian states were still jockeying for control of border lands and where ethnic tensions that had been held in check for decades under decades of communist rule, continued to unravel in violence. The Middle East, where Operations Northern and Southern Watch continued unabated, with no end in sight, and where Iran continued to pose a meddlesome threat requiring continuous U.S. military presence in the region.

Many also saw another potential threat rising on the far side of the world. While Britain had turned Hong Kong into an elite island city-state, an international economic powerhouse, time was running out on a 99-year agreement that allowed British rule. On July 1, 1997, weeks before Fogleman retired and just months before Ryan took over as CSAF, the United Kingdom completed the ceremonial transfer of power in Hong Kong, returning sovereignty to China after a century and a half of British rule. Now, just eight years removed from the Tiananmen Square massacre where China’s People’s Liberation Army had brutally crushed a civilian protest, China was taking possession of a vital connection to world financial markets. Hong Kong’s ticket to modernize its economy, and it pledged to uphold a “One Country, Two Systems” policy that would protect Hong Kong’s independence.

But China was not Ryan’s worry. His eyes were set firmly closer to home.

“I was terribly worried about how to protect the Air Force,” Ryan recalls now. “How do we stabilize this thing so it can’t just keep being eaten away?”

Every element of the Air Force was under attack. “Pieces grabbed. Every piece of your force structure questioned,” Ryan recalled. Questions flew: “Why do you need that?” The entire service was on the defensive, Ryan described. “It was—it was awful.”

From the outside, the Air Force seemed not to have any difficulty. There were plenty of planes—even if those planes weren’t all interchangeable. The Air Force lacked a simple force structure that could be explained in building block form, like the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. The Army had divisions, which were not all equivalent, but at least sounded as if they could be somewhat interchangeable. The Navy had carrier battle groups and a rotational model that resulted in predictable deployment and maintenance cycles. The Marine Corps had Marine Expeditionary Forces, which worked similarly to the Navy model.

But the Air Force had been built around its bases, its forces tailorable to mission needs. So as demand rose and the service shrank, cracks were beginning to show. Readiness and morale began to slide, right along with the declining budget.

Ryan noted how the Air Force built stand-in forces for those times when the Navy could not provide aircraft carrier presence in the Persian Gulf. This was the Air Force being expeditionary in its own right, as it had been in World War I, in south Asia in World War II, and in the Middle East since Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

“I said, ‘What if we took our Air Force and cut it up in a way that we could form these AEFs—Air Expeditionary Forces?’” Ryan said. If that concept were applied not just for gap-fillers, but for all operations, he thought, it would benefit the Air Force in myriad ways. “We could put some stability into our operations, we could say this is what the Air Force is made of—10 AEFs—and that’s something we can build a force structure against.”

Brig. Gen. Charles F. Wald was Ryan’s special assistant for the upcoming quarterly defense review, and he asked Wald to work out how to make the concept work. The model Wald’s team built meant the AEF could be used to size the force, Ryan said. “We used it as a force structuring tool, too, not just a tool to put stability into the rotations, but as a tool to say, ‘This is how many F-22 squadrons we need.’”

When then Air Force was ordered to cut the original F-22 planned purchase from 750, Ryan said, the Air Force used its 10 AEF model to rationalize a new figure: Every AEF needed at least one squadron of F-22s, and every squadron needed 24 planes; add in 25 percent more for training, a percentage for attrition, testing, and so on, and the requirement came out to 381.

The AEFs did not exist in a vacuum. The National Defense Strategy required a force able to fight two major regional contingencies at approximately the same time. The Navy drew the line at 11 carrier battle groups “and anyone who ever questioned that, they’d say, ‘No, we have to have 11 carrier battle groups,’ and no one would take that on.”

Ryan believed the AEF construct “would have legs” and survive because “it was designed to be able to handle an op tempo that was constant, because you could put two AEFs online at any one time, and that was plenty for what was going on. And if you had the big one, we’d go back to mobilize, just like for every other war we’d ever had.”

Defining an AEF for outsiders was never as simple as defining a carrier battle group, however. A carrier battle group could be seen in a photograph, and that image could be held in the mind’s eye. When the Air Force laid out its AEFs, however, it lacked that visual element. Instead, it was a complicated list: combat, mobility, and “low-density/high-demand” forces, delineated as wings, air groups, and squadrons, drawn from the Active, Reserve, and Guard components, and organized by date ranges. A separate list included support forces, organized by duty location. To show all the pieces of all 10 AEFs required two-and-a-half printed magazine pages in Air Force Magazine’s Almanac; even then, one needed to view all three pages to understand the contents of a single AEF.

Ryan’s AEF settled on deployment rotations of 90 to 120 days, another element that outsiders found difficult to fathom. The Navy and Marine Corps used six-month rotations. But the Air Force had set out to ensure units maintained proficiency in the full range of missions each one might face. That drove the decision for short rotations. “We thought we could keep proficiencies up if we had shorter deployments,” Ryan insisted. “You have readiness requirements you lose when you’re deployed. You don’t do certain things because of the kind of missions you’re force into when deployed, so you can lose your proficiency after 120 days if you haven’t shot a missile, or refueled, or any number of kinds of things you’re required to [be able] to do.”

But short cycles became unsustainable after 9/11, with the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, especially when the Army found itself forced to extend some deployments to 15 months, and to impose stop-loss orders that kept deployed Soldiers on Active duty beyond their enlistment dates. Would Ryan do things differently if he could go back and get a do-over? He’s not sure. He sees the argument for six-month deployments, as well as the benefits of 120. “What kinds of deployments are you going on? What kind of a beast are we feeding?”

The AEF construct survived the transition to Ryan’s successor as CSAF, Gen. John P. Jumper, but began to come apart under his successor, Gen. Norton A. Schwartz. Today, the Air Force is trying to establish a new means of presenting forces. The “force generation” model introduced late last year by CSAF No. 22 Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. establishes four six-month stages—commit, reset, prepare, and ready—for every unit, underscoring that the requirement Ryan identified for stabilizing the force in the late 1990s endures, even if the solution has remained elusive over the quarter century since he became Chief.

The undoing of the AEF may have been its flexibility, Ryan suggests. “Flexibility is the enemy of stability,” he said. “And unfortunately, air power is very flexible.”

Protecting the People

Ryan had more on his plate than combat rotations and deployments. The situation in the former Yugoslavia was still troubling, and the Air Force was on continuous duty there, as well as in the Middle East. Meanwhile, the military was facing other problems.

The Clinton administration had capped military pay growth below wage inflation in 1993. By 1997, the caps had opened up a 9 percent gap between military and civilian pay, according to RAND Corp. estimates at the time. This came on top of an estimated 12 percent gap that had grown since the 1980s. RAND and others questioned whether that gap really applied to the full force, or only to certain service members, but there was no escaping that military pay had fallen behind—and that recruiting and retention were beginning to demonstrate that fact. Another change Congress made in the 1980s was also coming into focus. Lawmakers had changed the formula for military retirement in 1987, but many in the military did not begin to recognize the difference until the late 1990s.

“Recruitment and retention were a big issue when I came on board,” Ryan said. “We had never advertised before that.”

Pilot retention was also a problem. “During the drawdown we had made a huge mistake: We had tried to throttle up and down the number of pilots that we would put out in a year. … But we had no way of predicting the run on our force that came from the airlines. Or how much our young force would decide after X amount of time they wanted out. Or what kind of payback we’d get from any of our” incentive programs. “But never pull it back,” Ryan said. “Because when you pull it back, you lose the instructor pilots, you lose range capability, you lose airplanes.”

But then, Ryan added a wrinkle. Those who agreed to let the Air Force train them to be pilots also agreed to stay in the service for 10 years. “My personnel guys said, ‘No—we can’t do that!’ But I said, ‘Yes, 10 years, you go to pilot training, you give us 10 years back.’”

The increased commitment had no impact on the take rate, Ryan said. But 15 years later, the Air Force is still struggling to retain enough mid-career pilots. Why? “That goes back to that stability issue,” Ryan said. “If the family is unhappy because they don’t have that stability, then it’s very hard to keep the member.”

Having tried advertising for new recruits, Ryan was now interested in leveraging that kind of marketing power for retention. “I looked around and I said, ‘We don’t have a rallying symbol in the Air Force, we don’t have a symbol.’ I mean, the Marines have their eagle, globe, and anchor, and the Army has their star, and the Navy’s got a lot of anchors. Well, we don’t have anything.”

Ryan hired some “Fifth Avenue guys” from New York and took their renderings to a Corona meeting of the Air Force’s four-star leadership. “There was one that stood out above the others,” Ryan said. “And that’s the one we have today.” But it wasn’t really that simple. He launched the symbol in a guerilla marketing campaign, using it as an unofficial logo in Air Force ads and waiting to see if it caught on organically. “I said go put it on a couple of water towers, put in on the front gate in a couple of places, but don’t force it. … And it caught on big time.”

Ryan said on issues of style, rather than substance, it’s better to let people buy in than to force change. In the end, it was Ryan’s successor, Jumper, who made it the Air Force’s official logo. But by then it was already widely recognized and accepted.

Not taking credit and letting things percolate is also reflected in Ryan’s approach to Corona meetings. All Chiefs have experience in Coronas before they are running them. When they finally are in charge, they have a very good idea of what they think is going to work. “First thing is: You’re not the smartest person in the room, and if you think you are, you’re not going to learn anything.”

“Make sure you include everybody’s opinion, and listen to them because someone in there has got a better idea than you do—or can take your idea and make it even better,” Ryan said. “When you go into executive session at Corona, that’s an important meeting. People can say what they need to say and give their honest opinions without fear of being chastised. I had some wonderful, cooperative four-stars that were my guys. They helped me a lot. … I didn’t have a maverick in the group in the sense of a guy who was fighting where we wanted to go. And we had some that had a lot of opinions and a few that had a bit of an ego, but everyone of them in the end were on the team. Everyone of them was an Airman. A team player.”

Ryan had a lot to live up to as the second Ryan to become Air Force Chief. His father had been a highly decorated bomber pilot in World War II, with two Silver Stars and a Purple Heart for being wounded on an antiaircraft fire on a bomber mission. “He was a hero in my eyes, not just because he was my dad, but because of his background. He took me up in a B-26 when I was about 10 years old, and he was a commander at Carswell Air Force Base, Texas. And from then on, I wanted to fly airplanes.”

The elder Ryan impressed his son with his “ethical quality that was unquestionable … and I vowed that I would try and live up to that too. Integrity ought to be your watchword, because if you don’t have integrity, you have nothing. You’ve got to admit when you’re wrong, and you’ve got to stand up and say so when something is your fault.”

When Air Force Capt. Scott O’Grady was shot down in Bosnia, Ryan said, it was his fault. “I put them in a position where they were vulnerable,” he said. “So Scott got shot down because of me.”

A few years later, another Airman was shot down, this time in Serbia. The pilot, then-Lt. Col. David L. Goldfein, had been an aide to Ryan earlier in his career, and Goldfein’s brother Col. Stephen Goldfein was Ryan’s aide at the time. Ryan said the day “Fingers” Goldfein was shot down was his worst day as Chief. When he finally got word that Goldfein had been rescued, he called Stephen. “I’ve got some good news and some bad news,” Ryan told his executive aide. “The good news is we got your brother back. The bad news is the Goldfein family owes the Air Force one F-16.”

- Chiefs, Part 1: Discordant Visionary

- Chiefs, Part 2: A Quest for Stability, A Last Stand on Integrity

- Chiefs, Part 3: Like Father, Like Son

- Chiefs, Part 4: ‘I Tried to Always Make Things Better’

- Chiefs, Part 5: ‘Buzz Was Right’

- Chiefs, Part 6: ‘The Accidental Chief’

- Chiefs, Part 7: ‘Surviving the Budget Control Act Debacle’

- Chiefs, Part 8: The ‘Joint’ Chief

- Chiefs, Part 9: ‘Last of the Cold War Chiefs’

- Chiefs, Part 10: ‘The Invisible Chief’