Following the carnage of trench warfare in World War I, airpower enthusiasts imagined a new kind of combat that would reduce the human toll of war. That goal still remains, but even with today’s precision weapons, civilian casualties are a constant risk. Now some see artificial intelligence as a means for minimizing civilian casualties, even as others argue technology is no substitute for warfighters’ professional judgment.

The laws of war require military forces to distinguish between combatants and noncombatants. U.S. forces seek to ensure that if civilian casualties occur in a given strike, they should be “proportional” to the importance of the target. Balancing these factors is among the challenges faced by planners and targeteers.

“These kinds of tools are very, very useful,” said retired Lt. Gen. David Deptula, dean of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, who led air operations during the early years of Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. “I embrace them.”

But the limiting factor on decision making in OEF was not a lack of intelligence or technology, Deptula said, but rather policy restrictions imposed on planners. “We could not drop a bomb anywhere in Afghanistan in the early stages without the four-star general in charge of CENTCOM approving each and every one,” Deptula said. Once, in fact, the restrictive rules of engagement led the U.S. to pass on a chance to kill Taliban leader Mullah Omar and his associates, Deptula said. “How many people died because we didn’t take them out that night?”

AI could slash the time and increase the accuracy of target vetting, potentially giving commanders greater assurance that collateral damage can be minimized. Engineers at Palantir, the data technology contractor that has played a key role in the Pentagon’s Maven system, showcased that concept at a recent AI expo in Washington, D.C., demonstrating software that can analyze data from multiple sources to better identify whether civilians are in or adjacent to buildings proposed as targets.

In theory, at least, those assurances can overcome the delays that often plague planners as they select and assign target sets. “Back in 2015 during operations against ISIS in Syria, the planners at the Combined Air Operations Center told me it could take over 45 days to get a target approved for a strike,” Deptula said. “That was a direct result of the restrictions that had been imposed on them: that some targets could not be attacked without 100 percent certainty of zero collateral damage.”

New Tools

Palantir’s Collateral Concern Check Framework requires operators to check a user-curated set of data sources for information about potential civilian buildings nearby, like schools, hospitals, or housing, where non-combatants might congregate, explained Arnav Jagasia, a software engineer on the firm’s Privacy and Civil Liberties team.

“We built it to be data agnostic,” Jagasia said, “It runs a radial search [a search over territory within a certain distance of a proposed target] against whichever sets of data the customer wants.”

Data sets can vary from one operation to another but always include the global No Strike List (NSL), a canonical listing of certain civilian facilities located throughout the world.

Commanders “can choose what [other] lists of data that collateral concern check must be backed against, and can have multiple such checks” throughout the targeting process, he said. The radius from the target that gets examined, the data sets that get searched, and the number of collateral concern checks are all up to the user.

Palantir sees potential for adding other data sets that can inject more timely intelligence into the decision process. Because the NSL data can be out of date, such additional sources—like location data for cell phone users, recent photos or videos gathered from social media or captured by nongovernmental organizations—can augment what targeteers know and the confidence they have about potential civilian casualties.

“A lot of information about the civilian environment doesn’t come from structured data sources,” said Jagasia; reporting from news organizations, NGOs, or aid workers can sometimes be PDFs, videos, photos, and social media posts. “There’s a lot of interesting and relevant data that is in unstructured format.” But the volume of the data and the speed of the targeting cycle make it extremely difficult to incorporate these sources into a manual process.

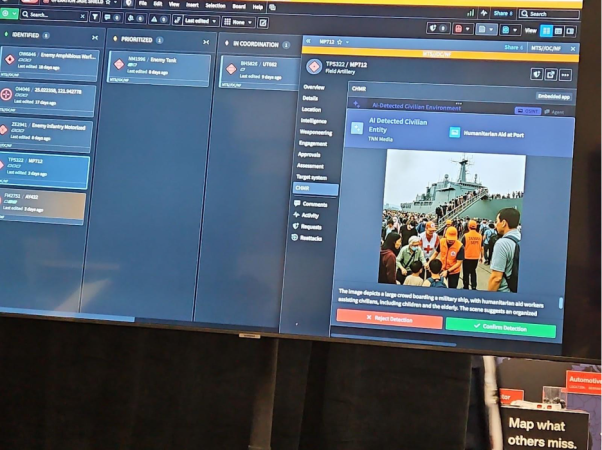

Targeting Workbench, a Palantir application used by the U.S. Air Force contains AI tools which can be used, as in this demonstration from June 2025, to scan unstructured data sets for information about potential civilians on the battlefield. Photo by Shaun Waterman/Air & Space Forces Magazine

Human Factors

This is where Palantir sees the potential for its AI tools, said Esteban Burgos-Herrera, another Palantir software engineer.

Their Target Workbench application is a decision support tool for targeteers, with optional integrated AI that can scan data sources for insights on whether civilians or civilian infrastructure are at risk.

“We can see different AI detections of civilians in the environment … tracking transient civilian presences that may be difficult for our users to capture otherwise,” said Burgos-Herrera. Users can reject or confirm the additional data, which can then be included in collateral concern checks.

Burgos-Herrera stressed that the AI is informing the decision-makers, not making decisions. “We’re giving a trained targeting officer tools that they can use to make those decisions with better data,” he said. “Targeting decisions are subject to international humanitarian law, as well as the rules of engagement for the operation. That’s fundamentally a decision that a human should make.”

Lauren Spink, senior research advisor at the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC), a nonprofit that advocates for fewer civilian casualties, agreed that “humans should remain accountable.” She sees AI as potentially helping “militaries improve their track record on civilian casualties.”

In 2022, then-Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, building on the work of his predecessors James Mattis, Mark Esper, and Christopher Miller, signed off on a “Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response” (CHMR) Action Plan, outlining measures the Pentagon would take to reduce the risk of unnecessary civilian casualties as a result of U.S. military operations.

“The excellence and professionalism in operations essential to preventing, mitigating, and responding to civilian harm is also what makes us the world’s most effective military force,” Austin wrote.

The origins of the Action Plan lie in the first Trump administration, when in 2018, Congress mandated DOD to create a Civilian Protection Center of Excellence to develop training programs and doctrine to reduce the civilian toll in U.S. wars. President Trump’s new administration has sought to shutter the center of excellence but needs Congress to reverse that requirement in law, according to a DOD official familiar with the issue, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the news media.

All Out War

The Action Plan insists it “is scalable and relevant to both counterterrorism operations and a large-scale conflict against peer adversaries.” But Deptula posits that a targeting system built for counter-insurgency is unlikely to be useful in a conflict with a peer competitor like China, where the pace, scale and context of operations will be more like World War II than Afghanistan or Syria.

“It’s a completely different situation,” he said, suggesting the target sets will be in the thousands or even tens of thousands daily, compared to a handful of daily sorties in Global War on Terror operations.

“I am not going to be using these tools to determine how to take out the invasion force that’s coming across the Strait from mainland China to Taiwan,” Deptula said. “And I’m not going to be using these tools to determine how to sever the lines of communication from Beijing to the ninth military Regional District in Nanjing. They’re just not applicable,” in those situations, he said.

In Afghanistan, high-value targets were moving from one home to another in an SUV; in a peer conflict, the targets would be infrastructure and military leadership.

“The high-value target in the case of China, is the commander of the Strategic Rocket Forces,” Deptula said. “He’s not going to be surrounded by civilians. He’s going to be located in a hardened and deeply buried command-and-control center somewhere in the eastern provinces [where] … collateral damage is not an issue.”

But where speed becomes a central factor in decision-making, policymakers and military leaders confront “terrifying” realities, said the DOD official. “When you’re using speed to your advantage, there’s a much higher risk for civilians,” the official said. Jamming and spoofing by China could cause some weapons aimed at military targets to strike civilians instead, increasing risk, the official added. “If there are things that can be done to make it even a little bit less of [the humanitarian] disaster it will definitely be if it comes to pass, we should consider doing those things.”

For the military, these are not theoretical issues, said retired Brig. Gen. Houston Cantwell, a senior fellow with the Mitchell Institute.

In 2010, while flying a two-ship of F-16s escorting a large Army convoy in Afghanistan, he saw the convoy come under fire as it entered a town. “Through my night vision goggles, I saw rocket propelled grenades, heavy machine guns, and they were taking fire from four different directions.”

The rules were clear, he said: “You always have the inherent right for self-defense, and American forces were under attack.” Dropping 500-pound bombs on the buildings from which the fire was coming would have complied with the laws of armed conflict and rules of engagement. But Cantwell reasoned the bombs would have also destroyed nearby structures as well, with untold civilian casualties.

“In the end, my wingman and I decided not to drop any bombs on these firing positions, because they were in the actual town and we were too worried about collateral damage,” Cantwell recalled. Although U.S. forces were taking fire, it didn’t appear to be effective fire. “There were no vehicles exploding. People weren’t being killed,” he said, and more appropriate fire support was nearby: An AC-130 gunship arrived 15 minutes later and took out the firing positions.

Decisions like that demonstrate American values in combat, Cantwell said. “If we indiscriminately start killing civilians, we are going against every principle that we stand for, and so it’s important that we do everything we can to minimize civilian losses as we try to execute these very complex operations overseas,” he said.

Complexity and speed are at the heart of the Air Force’s strategy to gain advantage over its peer adversaries. That’s why the service is pursuing AI across its spectrum of operations. If AI can speed up the targeting process, it can accelerate decision cycles and maximize U.S. advantages. In June, the 805th Combat Training Squadron at Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., tested an AI tool designed to offer “real-time recommendations to dynamic targeting teams,” according to a release. The aim was “to reduce cognitive load and speed up elements of the Find, Fix, Track, Target, Engage, Assess, or F2T2EA, process.”

Spink sees “a tension between the speed that AI could offer in this process and the need to thoroughly assess the human environment to ensure civilians aren’t accidentally killed.”

She cited Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza and a Washington Post investigation that found the Israeli Defense Force used AI tools to generate targets in order to keep up the pace of strikes even after it had exhausted a list of Hamas targets compiled over years prior to the war’s start. At the same time, the IDF reportedly raised its threshold for acceptable civilian casualties from one to 15 civilians per high-level Hamas operative. Spink suggested that further boosted civilian casualties.

The IDF, for its part, has said human analysts make the final call on targeting decisions, and that their decisions comply with the law of armed conflict.

Spink sees other uses for AI, such as more accurate modeling of “how the deployment of certain weapons could be expected to damage critical civilian infrastructure” and to more thoroughly take into account local building materials, terrain or other factors.

The military already does extensive modelling and analysis to select the optimum weapons for destroying certain kinds of targets, such as the Massive Ordnance Penetrators used in the U.S. strike on Iranian nuclear facilities in June.

Ultimately, the primary objective in war is to defeat the adversary, Cantwell said. “We want to kill the enemy before the enemy kills us,” he said. “That’s the bottom line. And a collateral effect of that desire is that there should be fewer civilian casualties overall.”