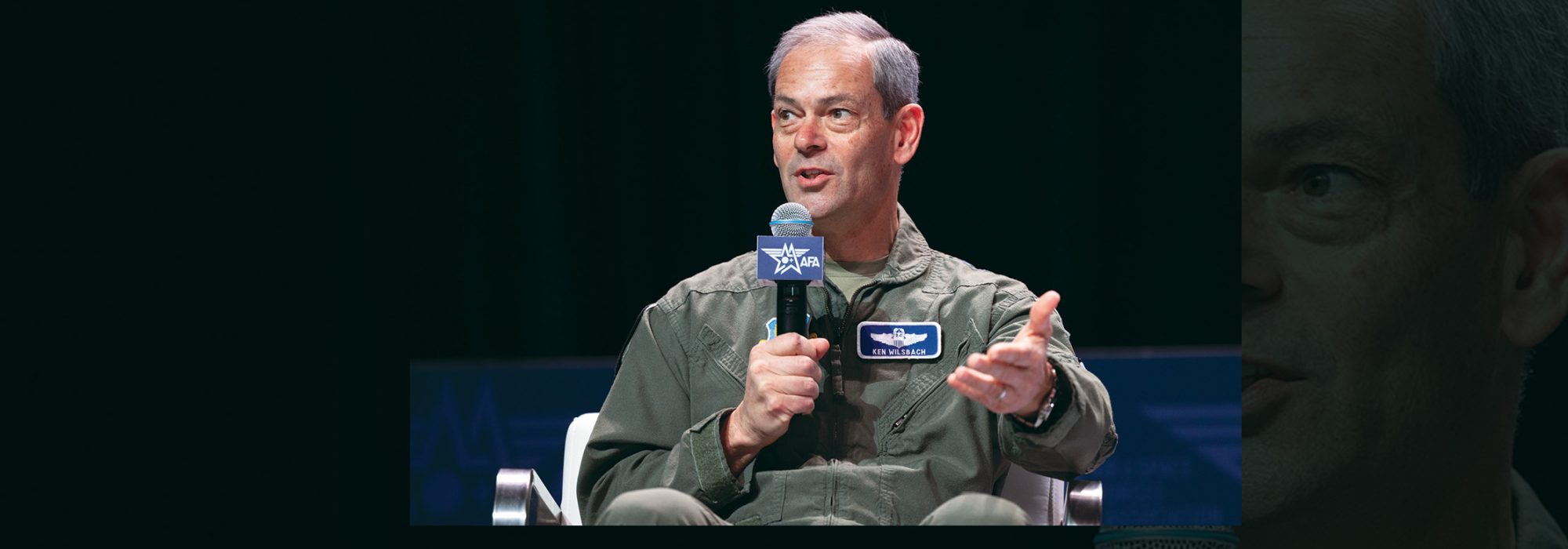

Wilsbach Is Air Force’s 24th Chief of Staff

By Greg Hadley

Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach was confirmed as the 24th Air Force Chief of Staff Oct. 30 by unanimous consent. Shortly before, his predecessor, Gen. David W. Allvin, was “clapped” out of the Pentagon, 10 weeks after he unexpectedly announced his retirement on Aug. 18, two years into his four-year term.

Wilsbach, a fighter pilot whose last assignment was atop Air Combat Command, takes over the Air Force as it works to overcome readiness challenges and to modernize its aging air fleet. Prior to taking over ACC, the Air Force’s largest command, he headed Pacific Air Forces, the Air Force component of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

“I’m deeply honored by the nomination to serve as the next Air Force Chief of Staff,” Wilsbach said in a statement. “The trust and confidence placed in me is not something I take lightly. If confirmed, I intend to strengthen our warrior ethos and to build a more lethal force that is always ready to defend our homeland and deter our adversaries around the world.”

Allvin congratulated Wilsbach in a statement: “I wish him all the best and trust that he will continue the momentum and advocate for the best interests of our Airmen, today’s readiness, and modernizing our force for the future fight.”

A fighter pilot by trade, Wilsbach most recently served as head of Air Combat Command, the service’s biggest major command responsible for the bulk of its combat fleet. There Wilsbach stressed readiness and standards, calling out a “discernible decline” in commitment to and enforcement of Air Force standards among commanders and NCOs, and directing inspections to address the issue.

He developed a new metric to measure aircraft readiness including monthly briefings to him on the health of the fleet, a move that seemed to dovetail with Allvin’s vision that ACC take on an expanded role in “generating and presenting ready forces.”

Wilsbach headed Pacific Air Forces prior to ACC and has a long history in the Indo-Pacific, having commanded the 7th Air Force in Korea, the 11th Air Force in Alaska, and the 18th Wing at Kadena Air Base, Japan. He did stints at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command and PACAF headquarters, experience that will be valuable as the Air Force girds for deterrence and potential future combat scenarios in the Indo-Pacific to counter China’s regional and global ambitions.

Wilsbach also inherits an Air Force with massive modernization requirements, an aging and shrinking force, and challenges in many of its acquisition programs, including the F-35 fighter, KC-46 tanker, and T-7 trainer, all of which have hit speed bumps, and future platforms that are further out but so far appear to be on track, including the B-21 bomber, autonomous Collaborative Combat Aircraft, and the F-47 penetrating fighter. The biggest program of all is the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program, which will cost in the tens of billions of dollars and is already over budget and behind schedule.

Facing all this and dealing with limited resources, Allvin and his predecessors have had to choose whether to prioritize readiness for the fight tonight or a potential future conflict. It’s a choice Wilsbach will likely face as well, unless he and other Air Force leaders can make the case for more funding.

Wilsbach’s appointment puts a fighter pilot in the Chief’s office, joining 11 of the past 13 CSAFs who likewise were fighter pilots. Prior to the 1980s, the Air Force had been led by bomber pilots.

In a statement of support for Wilsbach, AFA President and CEO retired Lt. Gen. Burt Field urged the Senate to swiftly confirm him. “General Wilsbach’s demonstrated leadership at every level, strategic vision, and extensive experience in the Pacific theater, as well as his command of Air Combat Command and Pacific Air Forces, ideal preparation for this important assignment. Now, more than ever, the Air Force needs bold and innovative leadership as it modernizes in response to growing threats around the globe, and especially in the Indo-Pacific region,” Field said.

Readiness Takes Center Stage

By Greg Hadley

In his first interview as Secretary of the Air Force, Troy E. Meink told Air & Space Forces Magazine that the extent of the Air Force’s readiness challenge was his biggest surprise in his first few months on the job.

At AFA’s 2025 Air, Space & Cyber Conference, he doubled down on readiness as a defining priority.

“I knew there was a readiness challenge,” Meink said in his first major address to Airmen and Guardians. “I didn’t appreciate how significant that readiness challenge was.”

Citing a recent visit to Joint Base Langley-Eustis, Va., Meink described seeing sidelined F-22 Raptors. “When there’s a number of aircraft, nonoperational, sitting around the ramp that aren’t even being worked on, because we simply don’t have the parts to do that, that’s a problem,” he said. “We have to fix that, and there’s a series of things I think we’re going to have to do.”

As the Air Force has reduced to its fewest tails in decades, Maj. Gen. William D. Betts, director of plans, programs, and requirements at Air Combat Command, noted that the readiness issue is becoming more pressing, shrinking the combat fleet even further.

“If you look at an [almanac] you would see a certain capacity, a number of fighters that the U.S. Air Force has,” Betts said in a panel discussion. “But the reality is that on any given day, there’s significantly less of those aircraft that are actually available and ready to fly.” Development and procurement of new aircraft will help grow the fleet. But the “fastest” way to address capacity, Betts said, is to make sure jets on the flight line today are ready to fly.

Or, as Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin put it even more bluntly in his last major speech as Chief: “Man, we’ve got to grow readiness.”

The Problem

At its core, the Air Force’s readiness challenge comes down to “flying and fixing airplanes,” said ACC Commander Gen. Adrian Spain. But understanding everything that goes into that is complicated.

“It’s hard to measure accurately, and it’s difficult to communicate concisely,” said Maj. Gen. John M. Klein Jr., who serves as assistant deputy chief of staff for operations. “I think we’ve struggled a long time with how we’re actually measuring readiness, and does that match up with what we’re presenting. … Readiness is not a single metric. It’s the amalgam of many different factors, and it’s mission-dependent. So a unit might be ready for one task, but not another.”

Mission capable rates—the percentage of a fleet that can accomplish one of its assigned missions over a given period of time—is traditionally the primary means of publicly communicating a sense of readiness to Congress and the administration. The Air Force has other more precise measures, including fix rates—the percentage of maintenance fixes completed within 12 or 24 hours—and flying hours, the amount of flying time pilots have to train.

Earlier this year, Air Combat Command introduced a new readiness model called “readiness-informed metrics.” RIM is intended to take percentages and abstractions out of the picture and to provide commanders throughout the chain of command a clearer picture of how many aircraft are available and whether a unit has enough or too little available capability at any given time. That data will not be released publicly, however.

Retired Col. John Venable, a fellow at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, has focused much of his research over time on the decline of flying hours and of appropriate funding to sustain and maintain aircraft so that pilots can get the reps and sets they need to be proficient.

During the Gulf War and at the end of the Cold War, Venable said, “the average pilot got over 200 [flying hours] and we considered anyone who got less than 150 hours noncombat capable. We would not send them to war.” By comparison, the Air Force now requires between 100 to 110 hours, depending on the experience level of the pilot—totals few pilots reach.

“We haven’t met that in several years, ladies and gentlemen, and that’s the minimum,” Venable said at the conference. “The numbers of hours our guys are getting are less than 120” per year.

Meanwhile, the aircraft are getting older, and the work required to keep them flying is taking longer. Meink even noted that on a recent visit to Guam, he saw the exact same KC-135 tanker he had flown decades ago as a young navigator.

“We will be maintaining aircraft probably that are 100 years old on the path we’re on,” he said.

Resourcing

The simplest way to improve readiness—at least in a vacuum—is more money. Klein said the Air Force’s Weapon System Sustainment account is funded at only about 80 percent of the required amount. That equates to a 20 percent shortfall in spare parts and repairs.

Meink said he intends to stop using readiness accounts as “bill-payers” for modernization or other priorities. He expressed gratitude for help from Congress, which passed legislation this past summer that included $2.5 billion for “facilities sustainment, restoration, and modernization”; $2.12 billion for “spares and repairs to keep Air Force aircraft mission capable”; and $250 million for “depot modernization and capacity enhancement.”

Yet the reconciliation bill was a one-time cash infusion, and rebuilding readiness will require tens of billions of dollars more over multiple years, Venable said in a recent research report.

While Meink has said he is confident that the White House and Pentagon will support more readiness funding in future budgets, he also argued that the Air Force will need to make hard choices with the money it does get.

“When you don’t have unlimited resources—which we don’t have—we need to make sure we are applying the resources we have for weapons system sustainment and readiness to the right and highest-priority systems,” he said.

Anything that’s “not capable of operating in a contested environment” is going to get second priority, he suggested, saying the service needs to “be second-guessing … how much money we’re dumping into readiness” for unsurvivable platforms.

Although he declined to specify the platforms he had in mind, Air Force officials have repeatedly called the A-10 Thunderbolt II unsurvivable in a peer fight. And the Air Force’s MQ-9 Reaper drones also lack the speed and stealth to survive in contested airspace. Indeed, they have been shot down repeatedly by Iranian-backed militias possessing far less sophisticated defenses than those belonging to Russia or China.

Yet any discussion over funding belies a key issue when it comes to fixing Air Force readiness, multiple generals said. The plain fact is that timelines and supply chains are also stretched thin.

“If we got $100 billion today to spend on parts, those parts wouldn’t show up for two to three years,” Spain said.

The Air Force uses the term “diminishing manufacturing sources” to describe the shrunken supplier base for older replacement parts.

There is also a people piece to the equation, Klein said: “You need maintainers to fix those aircraft, and it takes me five to seven years to grow” a seasoned aircraft maintainer. In other words, even if the supply chain could deliver, the Air Force lacks the maintenance personnel to catch up to its own repair backlog.

The number of enlisted maintainers in the force has dropped by thousands in recent years, according to data provided to Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Venable said leaders have no time to waste. “Our ability to fight tonight and the future of our capability begins today,” he said. “It doesn’t begin in seven years.”

Spain said the struggle must be a daily one. “I’m not rolling over on my back and showing my belly,” he said. “We’re going to fight every day to get a little bit better and a little bit more ready. … If I keep doing that with the resources and people that I have with me, and when those new resources come in, if they do, then we’ll be more appropriately equipped to take that on and to go faster.”

It starts, leaders said, by resetting how the Air Force views readiness to take a more holistic, nuanced view.

“For the last 30 years or so, we’ve kind of looked at it about the same way. I get X number of events done per month, and if I do Y number of events, I’m ready. If I do X minus one number of events, I’m not ready,” Spain said. But that approach doesn’t let commanders in the field allocate their resources in the best way possible.

“We have to give them the tools to really pinpoint how we’re using these resources, because when everybody has the same demand signal, you aren’t actually prioritizing how you spend those limited resources. You’re just trying to peanut butter spread it across the formation,” Spain said. “And so we have an opportunity coming forward to look at some things … in terms of competency mapping, proficiency-based training, and not just event-based measurement on a spreadsheet.”

Lt. Gen. John P. Healy, head of Air Force Reserve Command, said the Reserve is likewise focused on more precisely understanding its readiness challenge. As recently as 2021, when he was head of the 22nd Air Force, he said officials tracked flying hours by looking at last month’s data—too late to make any changes, a serious issue given that the Air Force often cannot execute all the flying hours its funded for in a year.

“We’ve got a data tool now in our flying hour program that allows me to go look yesterday, to the airplane, how we executed,” Healy said. “And we’re closing out the year, and we are on the razor’s edge to executing our flying hours this year.”

Balance

Readiness problems have been growing over time. In October 2018, then-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, stunned to find readiness levels hovering in the 50 to 60 percent range for front-line fighter jets, ordered the Air Force and Navy to achieve 80 percent mission capable rates. Only the Navy was able to make that goal. In 1998, then-acting Air Force Secretary F. Whitten Peters warned that engine readiness had “become a very significant problem.”

Readiness in the years after Vietnam were also an ongoing concern. In 1986, new Chief of Staff Gen. Larry D. Welch called “readiness today and readiness tomorrow” his top priorities.

Over the years, leaders have tried to improve readiness by pouring resources into different “foundational” accounts like manning, flying hours, weapon systems sustainment, support equipment, and infrastructure, Spain said. And while choices made were “entirely appropriate” at the time, he said, they have left things “out of whack.”

“One of the things that I know we’re working really hard on is rebalancing those foundational accounts,” Spain said.

Klein echoed that point, saying the service has been stovepiped in its approach to investing in readiness. He compared the situation to a 1980s boom box stereo: “If those knobs across the different frequency bands were off, you had some distorted music. So you need all those knobs set right to get the nice, clean crystal sound that you want so you can make mixtapes for your girlfriend,” he said. “They have to be balanced.”

Allvin said the Air Force will achieve that balance as it seeks “to put more parts on the shelf, to put more maintainers on the flight line, to put more velocity through our depots, to put more aircraft availability in the hands of our Airmen, to put more flying hours in to ensure our crews are ready, and continue that virtuous cycle, an upward spiral.”

And even with the issues the Air Force does face, Spain argued there should be no doubting the service’s capabilities.

“We still have the world’s greatest Air Force, and we’re [talking] about readiness challenges, but that is in the context of the world’s greatest Air Force,” Spain said.

Editorial Director John Tirpak contributed to this report.