By the turn of the century, the number of combat fighter squadrons operated by our allies in central Europe will decrease by thirty-five percent or more.

The drop will be most evident in squadrons with sole or primary missions in ground attack. On the other hand, air defense force structure won’t be cut and may, in fact, show some gains.

The units that do remain, particularly those in air defense, will be impressive. They will be able to engage enemy aircraft at greater distances, and most of the fair-weather day fighters will be gone.

By 2005, the average aircraft age will be about twenty years in the larger European fleets and upwards of thirty years in the smaller ones.

The variety of aircraft will diminish. Of the fighters flown in central Europe by non-US air forces, seventy-five percent will be of four types: the F-16, the Tornado, the Mirage 2000, and–assuming it is built–the European Fighter Aircraft (EFA).

The only new airplanes in sight are the EFA, designed for air defense, and the French Rafale multi-role aircraft. Neither of these “agile fighter” programs will put more than a few squadrons on the ramp by 2000.

These projections, made for the US Air Force by the RAND Corp., are based on an assessment of plans, budgetary considerations, and other constraints facing the German, British, French, Belgian, Dutch, Danish, and Canadian air forces.

Events in Europe are subject to surprising turns, of course, but there’s little chance that force structure will exceed the RAND forecast. If anything, “it could go much lower,” says Mark Lorell, who has been talking to the Europeans and updating the estimate.

| |

|

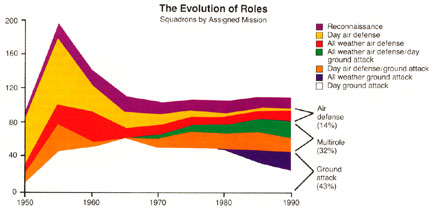

Today more than half of the Allied fighter squadrons in central Europe have attack as their only or primary mission. This is about to change. By the turn of the century, attack roles will diminish sharply and air defense will be the primary mission. Source: RAND Corp. |

Lorell, along with Christopher J. Bowie and John Lund, did a comprehensive analysis of trends in European fighter aircraft inventories from 1950 to 2005. It was published last year, just ahead of a wave of changes to plans for the 1990s.

It now appears that the drop in force structure will be roughly twice as severe as forecast a year ago, Lorell says. A formal revision will be published later this year.

Revised Projections

RAND now makes the following projections:

Attack mission. Today seventy-eight squadrons have attack as their sole or primary mission. By the turn of the century, the number so tasked will be between thirty-six and forty-one. With many air-to-ground munitions programs now canceled, the decline in attack is even sharper than aircraft totals indicate. European air forces will fall behind in their ability to fight modernized tank forces and other moving targets on the ground.

Demise of the day fighter. Virtually all attack aircraft in 2000 will be equipped to operate at night and in bad weather, compared to a third of them that can do so today. The capability will come from a combination of terrain-following radar, inertial navigation systems, on-board computers, and night vision devices, Lorell says. This will not match the Low-Altitude Navigation and Targeting Infrared for Night (LANTIRN) system that some US fighters have, but it’s a big step up from day fighters.

Air defense. Thirty-eight squadrons currently have air defense as their only mission or, in the case of dual-role units, as their primary mission. By 2000, between thirty-nine and fifty-four squadrons will be so assigned.

Beyond visual range. Slightly more than half of the air defense squadrons now have the all-weather capability to engage enemy aircraft beyond visual range. Virtually all of them will have this capability by the turn of the century.

Reconnaissance and EW. The reconnaissance effort will decline (from eleven squadrons to six or eight). There will be modest gains in electronic warfare capability. These missions, however, have never been major ones for the Europeans, and the changes will mean only marginal differences in the overall force structure.

Numbers and Diversity

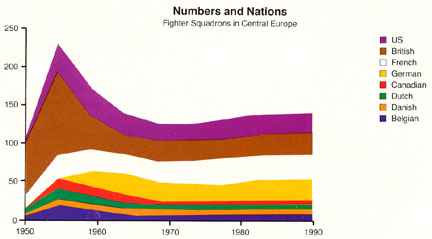

In the 1950s, when NATO was new and the Russians were scarier, the US and its Allies fielded almost 250 squadrons in central Europe. Force structure dropped sharply but steadily over the next ten years, then stabilized at about 140 squadrons in the late 1960s.

Any impression that the Allies kept cutting fighter force structure after the 1960s is wrong, RAND notes. The total number of squadrons and the number provided individually by each nation have remained essentially constant for twenty-five years. Expansion programs in the 1980s actually led to a modest increase.

At present, the European nations have 116 squadrons. (The total excludes US and Canadian units.) After the big drop coming in the 1990s, RAND believes, force structure will again level off, this time somewhere between seventy-five and ninety-five squadrons.

“The official French position is that there will be no cuts–zero–in their fighter-attack force structure, but we are projecting a decrease of thirteen to twenty-seven percent,” Lorell says.

RAND predicts that the Germans will cut their fighter force structure by twenty-four to thirty-eight percent and that the British will cut by seventeen to thirty-one percent. The Dutch, Belgians, and Danes, whose combined numbers are roughly equal to one of the bigger European air forces, will cut by twenty-seven percent.

Pure all-weather interceptor forces declined after the 1950s. In partial compensation for this, the Europeans have maintained about 100 squadrons or batteries of surface-to-air missiles for the past twenty-five years.

In a modest way, the all-weather interceptor is coming back. The nations with F-16A fighters plan to modify them to F-16C levels, and the Germans are upgrading their F-4Fs with look-down/shoot-down capability against multiple targets. The EFA would add a completely new air defense aircraft.

The Big Four

The diversity of aircraft has gone up and down. The Europeans flew nine major types of fighters in the 1950s. Variety reached its peak in the late 1960s with sixteen different kinds of fighters, a colorful panoply of Lightnings, Hunters, Mysteres, Vautours, Starfighters, and others.

Twelve major types will be in service in the early 1990s, dropping toward nine types by 2005. Seventy-five percent of future fighter fleets, however, will consist of F-16s, Tornados, Mirage 2000s, and EFAs.

The single most dominant airplane will be the Tornado. Operating in attack, air defense, and electronic reconnaissance variants, it will equip a third or more of the total squadrons. The ECR (electronic combat/reconnaissance) variant, currently flown by the Germans, was a breakthrough in electronic combat, which has traditionally been “one of the weakest areas of all for the Allies,” Lorell says.

The French continue to modify the basic Mirage 2000 for an assortment of uses. The latest is the Mirage 20000 (originally called the 2000N-Prime), which promises to be a very capable attack aircraft.

The big question is the future of the EFA, which, like the Tornado, is a multinational program. It has been beset with delays, cost escalation, design disputes, and other troubles.

Rollout is scheduled for later this year, with initial operational capability in 1996. If everything goes as planned, 765 aircraft would be built: The British and the Germans would buy 250 each, with the Italians taking 165 and the Spanish 100.

Modernization Through Modification

With each passing year, airframe fatigue problems will intensify for the systems in service now. A considerable amount of modernization is possible through system upgrades, but to remain credibly effective the Europeans will eventually need some sort of replacement aircraft.

The second generation of jet fighters followed closely on the heels of the first. In 1955, the average age of aircraft in the European fleets hovered around five years. Since then, fighters have stayed in service longer and the average age has crept steadily upward for several reasons.

“Some aircraft, such as the F-4 Phantom II and Mirage III, were brilliant designs that could be kept effective through upgrade programs,” the RAND report says.

“Other aircraft were modified to perform different missions. Perhaps most important, the increasing cost of these weapon systems made it more and more difficult to replace them as frequently as in previous years.”

The Europeans will continue to rely heavily on marginal gains from radar and avionics upgrades and the addition of new subsystems. An AMRAAM under the wing can do a lot to offset age creep.

There are limits to the “modernization through modification” approach. For one thing, it cannot incorporate stealthiness or other revolutionary technologies that call for new airframes.

Such technologies, however, are not likely for European air forces in the foreseeable future. That puts pressure on them to explain why the additional benefits of the new aircraft they propose are worth the investment.

A recurring question, as put to RAND by one Allied military planner, is, “Exactly what improvement will the EFA or Rafale provide over the F-16C?”

| |

|

Allied air forces have always provided most of the in-place fighters in central Europe. Both the number of squadrons and the relative contribution of each nation have remained relatively constant since the later 1960s. Source: RAND Corp. |

Nation-by-Nation Outlook

Here, as forecast by RAND, is the outlook for the seven Allied air forces in central Europe.

France. Mirage 2000 variants will steadily replace older Mirages and most Jaguars. Even if Rafale stays on schedule (it has shown a proclivity to slip), only a squadron or two will be operational at the end of the century.

Germany. Originally, Lorell says, the Germans wanted to replace six squadrons of Alpha Jet attack aircraft with the interdiction/strike variant of the Tornado. That deal fell through, and Luftwaffe procurement of attack Tornados has been terminated. Purchase of the ECR ‘Tornado continues. Upgraded F-4Fs will be employed for air defense through the 1990s but must be replaced soon thereafter with something, presumably the EFA. Germany is a full partner in EFA development but is not yet committed to procurement.

Britain. The Royal Air Force will lose five (of its current eleven) Tornado attack squadrons. Three will be disbanded, and two have been reassigned to maritime operations. Four air defense squadrons of F-4s and two squadrons of Buccaneers, which had a secondary ground attack mission, will also be disbanded. Three Jaguar squadrons are likely to go as well. The Harrier jump jet survives, and the British plan to field a GR. Mk. 7 night-attack variant.

Belgium. The Belgians are reducing their commitment of F-16s to NATO from 144 aircraft to 120. They will also fall back from two squadrons of Mirage 5s with a total of fifty-six aircraft to one squadron with twenty aircraft. They plan to buy AMRAAM for their F-16s, but that procurement could be reduced or delayed.

Canada. The present Canadian fleet, with an average aircraft age of eight years, is the newest in the NATO lineup. The Canadians have shown interest in LANTIRN pods for their multirole CF-18s.

Denmark. The Danes currently have four squadrons of F-16s and two of Drakens and had planned to convert completely to F-16s and AMRAAM. Now, RAND forecasts, they may replace only half of the Drakens. Lorell estimates the Danes will be effectively down a squadron or two entering the next century because, like the other F-16 air forces, they are not buying enough aircraft to replace normal losses to attrition.

The Netherlands. The Dutch field eight squadrons of F-16s but are reducing their commitment to NATO from 162 aircraft to 144. A few years back, seventy percent of their effort was on attack missions. Lorell reports that the present mix is fifty-fifty, air defense and attack, and that “they’ll be all air defense by 2000 with the present trends.”