After a year’s deliberation, the Air Force has decided not to develop Adaptive Engine Technology Program (AETP) powerplants for its F-35s, deeming the cost too high in light of other demands.

Instead, the service will go with a suite of upgrades for the existing F135 engine and press ahead with the Next Generation Advanced Propulsion project meant to power its next fighter, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said in a March 10 budget briefing.

“We needed something that was affordable and that would support all variants” of the F-35, Kendall said.

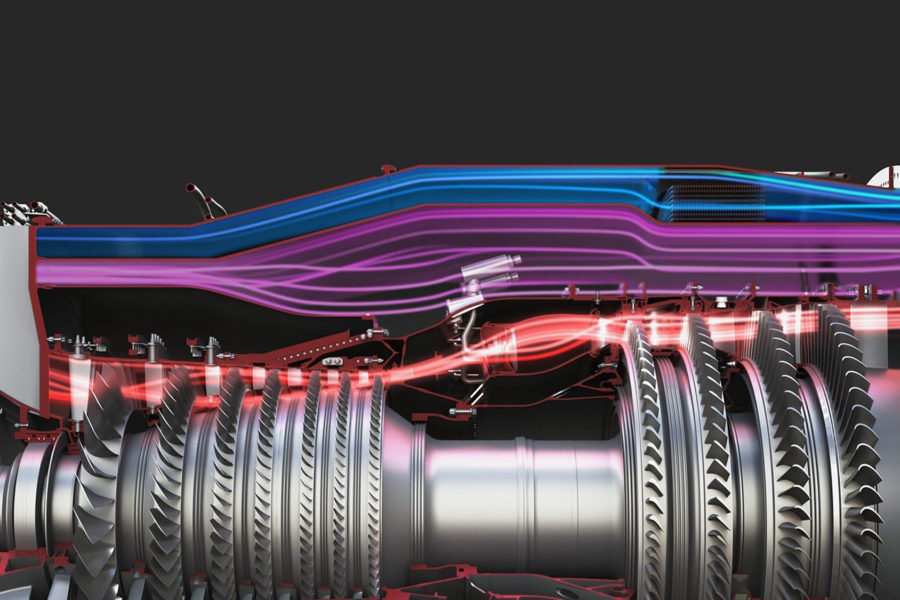

The upgrades to the F135, deemed the “Engine Core Upgrade” by contractor Pratt & Whitney, will deliver improvements to the engine necessary to meet the demand for additional power and cooling on advanced Block 4 versions of the F-35. Those specific Block 4 requirements have not been made public.

GE Aerospace and Pratt both developed competing powerplants under the $4 billion-plus AETP program—GE the XA100 and Pratt the XA101. The two engines achieved improvements of 30 percent in fuel efficiency and at least 10 percent in thrust compared to the stock F135.

However, both powerplants used a bypass air system to achieve the gains, increasing their diameter. While the new engines would fit comfortably in the F-35A used by the Air Force, they would be more challenging to adapt to the Navy’s F-35C and very difficult to fit to the Marine Corps’ F-35Bs, which use a unique short takeoff/vertical landing system with swiveling exhaust nozzles and a shaft connected to a vertical lift fan behind the cockpit.

While GE insisted the AETP could be made to work with the F-35B, Pratt said it could not. And while GE claimed that the new engine would ultimately provide savings of up to $10 billion due to fuel savings and less maintenance, Pratt argued its analysis found the development and integration of the AETP engines with the F-35, along with changes to the worldwide F-35 engine sustainment system, would cost $40 billion over the life of the program.

“We’re pleased to see the President’s Budget includes funding for the Engine Core Upgrade,” a Pratt spokesperson said. “All F-35 variants need fully-enabled Block 4 capabilities as soon as possible, and with this funding, we can deliver upgraded engines starting in 2028.”

The ECU “saves billions, which ensures a record quantity of F-35s can be procured,” the spokesperson added. “It also ensures funding will be available to develop 6th generation propulsion for the Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance Platform.”

GE Aerospace was—predictably—unhappy with the choice, saying through its spokesman that “this budget fails to consider rising geopolitical tensions and the need for revolutionary capabilities that only the XA100 engine can provide by 2028.”

“Nearly 50 bipartisan members of Congress wrote in support of advanced engine programs like ours because they recognize these needs, in addition to the role competition can play in reducing past cost overruns,” the spokesman added. “The XA100 engine is ready to power U.S. warfighters today and in the future.”

The company also claimed the $4 billion invested in AETP technology thus far “risks being wasted if the program is ended so close to completion.” Congress, the company said, will ultimately decide whether the AETP is funded or not—the legislature previously directed preliminary work to take place ensuring that F-35 engines could be upgraded with AETP technology by 2028.

GE also said it is continuing to test and develop the XA100 “while pursuing funding support for 2024.”

The engine maker derided the ECU as “an incremental upgrade to the current F135 engines” that would “still cost billions, without providing the same capability improvements as the XA100. Other so-called savings you might see are cost avoidance numbers disguising an increased baseline cost.”

However, given that within the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program, partners have to “pay to be different,” the Air Force would likely have born the entire cost of a new engine—leading to the decision to not proceed with AETP.

“This was based on the fact that the requirements were … applicable only to the Air Force,” and not “spread across the entire fleet of joint F-35s,” said Kristyn E. Jones, assistant secretary of the Air Force for financial management and acting service undersecretary.

“We’ve decided to move forward with the Engine Core Upgrade. We have $254 million in this year’s budget for that particular effort,” she added.

However, Jones said the money spent on AETP won’t go completely to waste.

“We do plan to leverage a lot of the capabilities that were part of the AETP prototype for efficiency, thrust … [and] thermal management, so it was not necessarily” a futile effort, she said.

“Those capabilities will be leveraged as we look at the next engines” under the NGAP program, which the Air Force seeks to fund at $595 million in fiscal 2024, up from $224 million enacted in the fiscal 2023 defense budget.

“We’ll be building on all the lessons learned” from AETP, Jones said, but she couldn’t offer a timeline of when test articles will be ready for that program.

The NGAP is intended to produce engines for the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter, the crewed centerpiece of a family of systems that is intended to provide air superiority in the 2030s. It isn’t clear how the NGAD development will proceed if its engines are being designed concurrently.

Deliveries of F-35s and F135 engines resumed recently after a two-month hiatus following an F-35B crash in December 2022. Pratt said it identified a “harmonic resonance” problem with the engine that only manifested after 600,000 hours of engine run time. The fleet has been directed to perform a retrofit in the field to correct the issue.