The F-35 is the most advanced fighter yet built, but decisions and compromises imposed on it more than a decade ago continue to push up its cost, decrease its reliability, limit its performance, and constrain its ability to exploit new technologies. For fighter pilots of my generation who lived through similar challenges, it’s a current reminder that we ignore the lessons of the past at our peril. The U.S. Air Force has long held a qualitative advantage over potential and likely future adversaries. It achieved that through hard work, hard fought wars, and sobering Cold War experiences.

What are those lessons?

- Ongoing competition is essential, especially in fighter engines.

- Requirements must be defined by warfighters and should not be budget-constrained.

- In air dominance, “there are no points for second best,” as the old Grumman Corporation used to say about its F-14. That lesson holds today.

- Commonality across service and partner fleets adds cost and invariably leads to performance compromises and disappointing suboptimizations.

Last week’s Paris Air Show contretemps between Lockheed Martin, maker of the F-35, and Pratt & Whitney, maker of its F135 engines, is a case in point. Lockheed called short-sighted the recent Air Force decision to shelve for now the promising Adaptive Engine Technology Program (AETP) in favor of an engine core upgrade (ECU) and Power Thermal Management System (PTMS) enhancement to the existing F135 engine. Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall had previously expressed his own reservations about the decision.

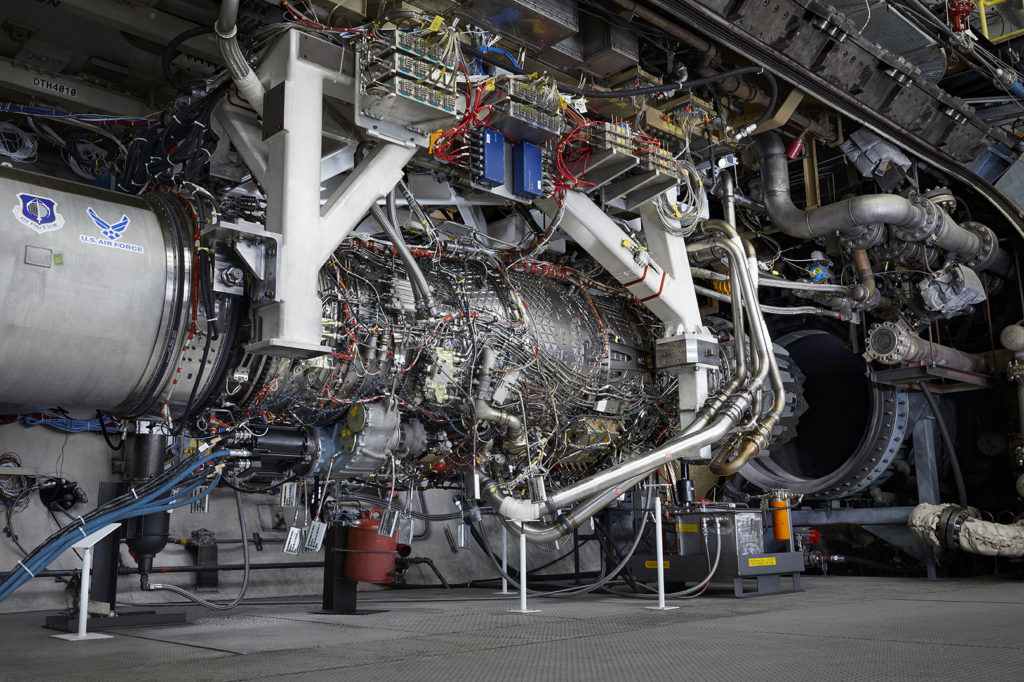

At issue is whether the F135 will ever produce the power and thermal management capabilities required by the ill-defined Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3) and Block 4 avionics enhancements. Pratt’s solution, which it admits offers limited potential upside but is theoretically least costly, is the ECU and improved PTMS. Pratt won the budget argument for inclusion of its answer in the Air Force’s 2024 budget submission.

At Paris, Pratt’s over-the-top reaction accused Lockheed of putting its wishes ahead of its customers, even as Pratt appeared to be doing precisely the same thing in protecting its perpetual lock on F-35 propulsion over acquiescing to an ongoing and open competition between Pratt and GE entries in the AETP.

Here, a historic review is instructive:

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the Air Force launched its fourth-generation fighters with a flawed sole-sourced engine. We bet the fleets on Pratt’s F100-PW-100 engine, only to find it not ready for prime time. Our provisioning plans were likewise inadequate. The result: USAF lagged requirements by 1.5 million turbine blades. Whole forming F-15 squadrons sat on the Langley Air Force Base ramp with empty holes where engines should have been. Meanwhile, F-16s risked stall-stagnations in fighter maneuvering, a problem that could only be cleared by inflight shutdown, if afterburner was selected below 250 knots and above 25,000 feet.

In Saudi Arabia, which had over-provisioned its F-15 engine spares against the day when the USAF might have to come from over the horizon to counter an existential threat to the Kingdom as in Desert Shield/Desert Storm, the initial provisioning of turbine modules was exhausted in 18 months, the result of turbine blade distress from the magnesium dust-laden air of desert operations. The “turkey feather” design of the F-15 nozzle fairings turned out to be a mistake, which resulted in the Eagles operating throughout their life without nozzle fairings.

Eventually, the consequences of sole-sourcing of our fleet’s engines to a single manufacturer were solved, of course, by competition. The F110-GE-100 and the common engine bays in later F-15s and F-16s made it possible to accommodate either Pratt or GE engines; continuing competition, in turn, met the evolving Air Force requirements for greater thrust and operational utility in the F100 with its -200, -220, and -229 variants. The GE Improved Performance Engine (IPE) -129 and -132 variants further pushed available thrust out from the F100-PW-100’s 24,000 pounds afterburning thrust to 32,000 pounds for the F110-GE-132.

These days, thanks to competitive engine and avionics upgrades, the F-16 is expected to remain in the fleet well past the 50th anniversary of its initial operational capability (IOC). Competition lesson learned—again—for Generation Four, the hard way.

Even so, that lesson was subsequently disregarded when it came to funding or even supporting an alternative engine for the F-35. GE developed and offered its F136 alternative, but the Pentagon cancelled the program, saving $5 billion in what is now ruefully accepted as a false economy. With hindsight, it’s clear that was a consequential mistake with implications for fifth- and sixth-generation fighters. The Government Accountability Office recently noted the suboptimization of the planned fixes to the originally “under-specced” F135 engine, pointing out that its lack of inherent bleed air and electrical power capacity and growth potential is resulting in overheating at such a rate as to consume spares at substantially greater rates than can be logistically supported.

Pratt’s ECU and vendor Honeywell’s PTMS enhancement solutions were originally touted as readily available and preserving commonality among the consortium partners’ variants. But it turns out that neither is now likely to be suitable in a single form even for the U.S. variants, and not currently “specced” or available before the early 2030s.

So much for commonality.

Collins, an affiliate of Pratt’s under RTX, senses a free-for-all; it is challenging Honeywell’s PTMS vendor lock. Meanwhile, the brilliant Adaptive Engine Technology Program (AETP) has been deferred as unaffordable now, its assets likely transferred to the Next Generation Advanced Propulsion (NGAP) program for the secretive gray world Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) system of systems, which reportedly has prototype(s) already flying.

AETP itself has been redesignated a ‘demonstration’, not a program, with its $4 billion in cumulative funding squeezed off beginning in fiscal 2024. This current status of the AETP is reminiscent of Bill Clements’ (and John Boyd’s) YF-16 and YF-17 lightweight fighter ‘demonstrators’ which, while not originally intended for production, morphed into the successful and ubiquitous F-16 and F-18 programs.

Similarly, the XA100 (GE) and XA101 (Pratt) ‘demonstrators’ would seem, given funding, to offer a major leap forward in fighter engine technology. The numbers projected for the AETP are mind-boggling in terms of extra thrust, extra bleed air and utility output, and hugely reduced specific fuel consumption on the order of 30 percent over current fan technologies. We should all beware of engine manufacturers’ projections, which can only be kept honest through test and head-to-head competition, but it’s clear the potential for these new engines is tremendous.

It is not clear from the open sources whether the essential, more art-than-science engine/inlet matching to the F-35 was part of the AETP demonstration and those projections. (The initial fitment of the GE110 to the F-16 with its original inlet was mismatched and required enlargement of the F-16 engine inlet to capture the extra airflow needed by the GE110.) Our fighter engines’ performance and reliability have long been the strength of our fleets, while the Chinese continue to struggle with their indigenous WS-15 engine development for the J-20, and the Russians still produce fighter engines with times-between-overhauls measured in hundreds, rather than thousands of hours as USAF’s are.

We should be funding our strengths in the 2024 budgets and beyond, and vigorously protecting our secrets.

Secretary Kendall has focused on the unavailability of sufficient resources within the Air Force budget share to fund both the ECU and PTMS upgrades to the F135 and the AETP. Here, our Navy friends have reverted to their decades-old playbook of letting the Air Force pay the cost of engine improvements and were unwilling to help fund the exploitation of the AETP. (It took the USAF-provided GE110 option to turn the F-14B/D into the dogfighter the Navy wanted when it bailed from the F-111 program—but didn’t get because it initially used the off-the-shelf F-111 engine with its thermal cycle limitations.)

Rep. Rob Whitman, chair of the House Armed Services Committee tactical air and land forces subcommittee, managed to insert into the draft 2024 National Defense Authorization Act the continuation of the AETP. It’s unknowable how the issue will fare in Appropriations and in conference, and whether the DOD would reconsider its decision and spend any appropriations for AETP if so prodded by the Congress.

All the above are facts the Fighter Mafia in the bowels of the Pentagon have doubtless argued with greater specificity and accuracy than I have here. It’s time for the leadership to listen one more time, and to reconsider. The resolution of this debate should be based on service-written requirements and strategic imperatives, not political or budgetary considerations, or even profit driven contractor intramurals.

Why now? Because the burgeoning threat to our remaining an Indo-Pacific and, therefore a global, power is China and the Chinese Communist Part.

Western Pacific deterrence, or the outcome of the potential fight over Taiwan should deterrence fail, will turn heavily on our present and future ability to seize, project, and sustain air dominance.

We must fund adaptive engine technology through tough trades—AETP vs. interim and stealth tanker/multimission platform force sizing, for example—and externally from rebalanced land force’s budget shares to field quickly this breakout Adaptive Engine technology. Doing so will ensure the U.S. retains air dominance capability and capacity over the vast reaches of the Pacific and contains China from pursuing by force the CCP’s ambitions.

In the words of Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., it is time to “accelerate change” and revisit and revise our current second-best course of action.

The Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC) would be a good place to start for a tough-minded scrub focused on the weapons and capabilities most needed to contain China. It’s a budget battle no one wants, but one which our Air Force must fight.

Col. Leonard “Lucky” Ekman, USAF (Ret.) was a fighter and Wild Weasel pilot who flew three tours in Vietnam, including 1,066 combat hours in the F-105. In between Vietnam tours, he was an Olmsted Scholar in Geneva from 1969-71. He spent his last decade in uniform as a pol-mil officer.