U.S. Central Command announced June 14 that Air Force F-22 stealth fighters have deployed to the Middle East, the latest action amid growing tensions between the U.S. and Russia in the skies over Syria—but also tied to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

“This is one place where combatant command [boundary] lines aren’t helpful,” Air Forces Central commander Lt. Gen. Alexus Grynkewich said at the Defense One Tech Summit. Grynkewich said he speaks with Gen. James Hecker, head of U.S. Air Forces in Europe-Air Force Africa and NATO Allied Air Command, more than any other air component commander “and it’s because of the confluence of Russian activity. … The center of gravity of what Russia is doing right now is of course in Ukraine, but we see that manifesting here.”

In particular, the U.S. has noted “increasingly unsafe and unprofessional behavior by Russian aircraft in the region,” according to a CENTCOM press release about the F-22 deployment. Grynkewich tied that behavior to the March 14 incident in which two Russian Su-27 fighters dumped fuel on and flew in front of a U.S. MQ-9 Reaper drone over the Black Sea. One of the fighters struck the drone’s propeller, forcing the U.S. to intentionally crash the drone, and the Russian pilots were honored by Moscow. That sets a precedent for Russian pilots elsewhere, Grynkewich argued.

“If you’re going to give medals to Russian fighter pilots for pouring gas on a UAV and then knocking it out of the sky by crashing into it while they’re operating over the Black Sea, then the Russian pilots that serve in other parts of the world such as Syria see that and that’s going to incentivize them,” he said. “Now we see similar aggressive behavior, not quite to that degree yet, but we see very aggressive behavior out of their pilots.”

In recent months, Grynkewich has spoken up about Russia upping its harassment of U.S. forces in Syria by overflying U.S. positions with armed fighters, closing within a few hundred feet of U.S. fighters. Air & Space Forces Magazine previously reported that in November, the Russians fired a surface-to-air missile that detonated within 40 feet of an MQ-9 and damaged the aircraft.

Grynkewich said the belligerent behavior could be driven by “a confluence of our adversaries.” As the Russian Air Force uses Iranian-made drones in Ukraine, the Russian government is compelled to act in Iran’s interests in a way which “has resulted in collusion, if you will, between the Russians and the Iranians, both of whom want to see us out of Syria,” he said.

That collusion gets in the way of the real mission in Syria, which is to ensure the enduring defeat of ISIS, Grynkewich added. Instead, Russia, Iran, and Syria seem to be focused on frustrating U.S. efforts there—though he claimed such attempts were fruitless.

“There’s no way they can actually push us out of the airspace,” he said. “I don’t think they want direct conflict with the United States, we certainly don’t want direct conflict with Russia. So to me it’s kind of akin to a gnat swirling around your head. It’s very frustrating and annoying sometimes, but in the end it doesn’t really matter.”

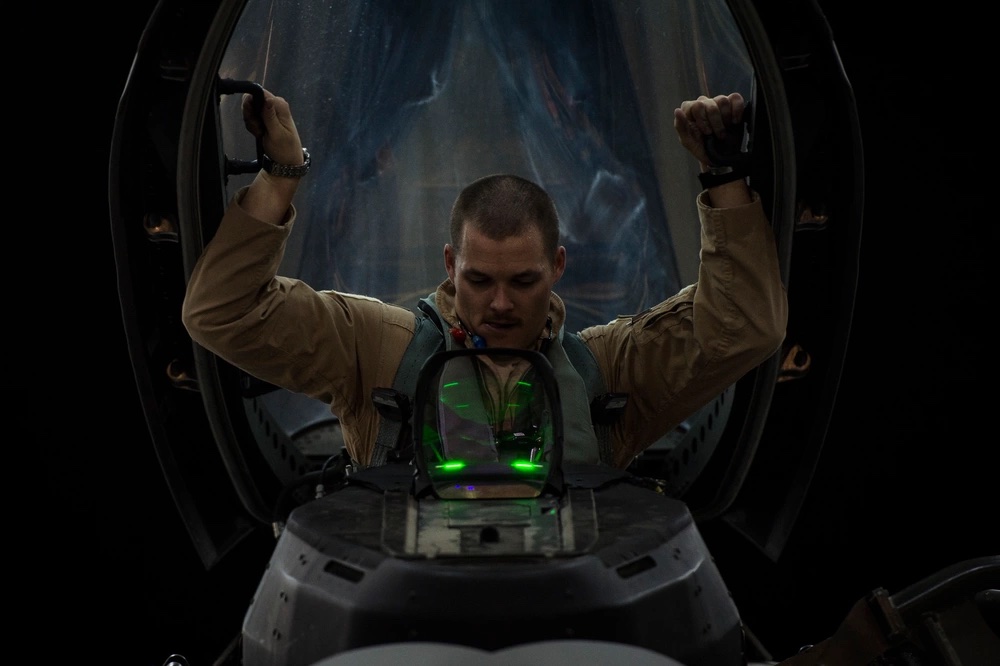

Even so, Central Command saw the need to bring in F-22s, as a reminder of America’s “ability to re-posture forces and deliver overwhelming power at a moment’s notice,” the command said in its press release. Still, Grynkewich said U.S. forces strive to maintain a “de-escalatory posture” in the region.

“We ought to all get back to focusing on ISIS and I hope they decide to do that,” he said.

Though U.S. military planners are increasingly focused on countering possible Chinese expansion in the Pacific, the competition with Russia in CENTCOM and China’s economic interests in the Middle East show that the region is still crucial, Grynkewich said. The Center for Strategic and International Studies reported that more than 45 percent of China’s oil imports pass through the Strait of Hormuz, and Grynkewich says China sees the Middle East in part as a gateway to the rare earth minerals located in Africa that are essential for both civilian and military electronic technology.

“Where the Chinese economic objectives begin, their military interests will follow,” said the general, who cautioned that if the Persian Gulf were to become “a Chinese lake,” it could severely limit U.S. options should war break out in the Indo-Pacific region.

At a tactical level, Grynkewich said many of the challenges U.S. troops face in CENTCOM are akin to what they may face against China in the Pacific. As China adopts an anti-access, area denial strategy using thousands of ballistic missiles and advanced air defenses in Pacific island chains, Iran is using a similar strategy in Southwest Asia, he said.

“The lessons that we learn here in AFCENT as we look at that tactical problem … after years of thinking just about violent extremist organizations, the lessons that we learn, I would posit are exportable across the entire globe,” he said.