President Donald Trump redubbed the Department of Defense “the Department of War” Sept. 5, adding to the ongoing questions about the limits of executive orders and lines between the White House’s legal authorities and those owned and controlled by Congress.

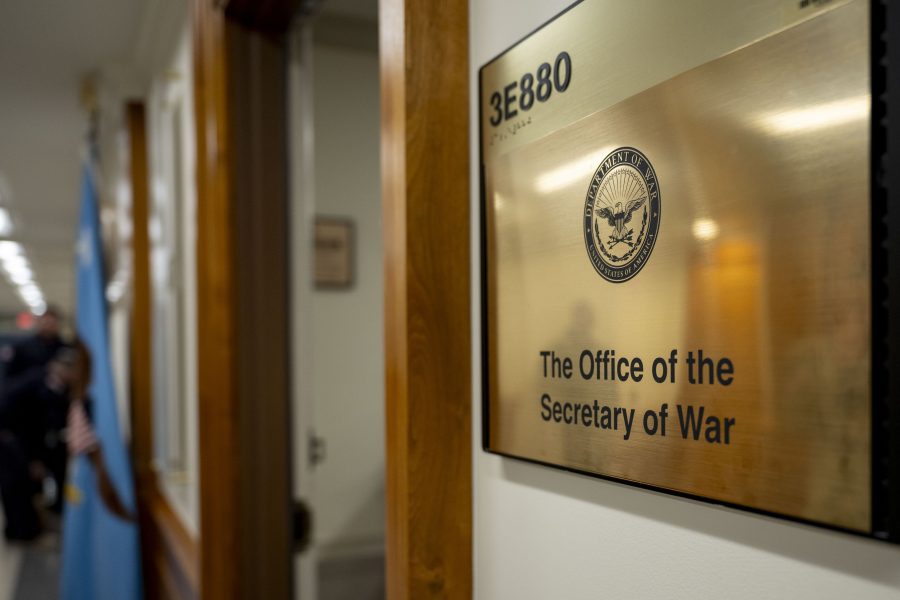

Minutes after the late Friday afternoon Oval Office announcement, workers changed the signs outside Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth’s office at the Pentagon, pulling off the letters that said “Office of the Secretary of Defense” and posting in their place “Secretary of War.”

Some lawmakers challenged the president’s authority to make the change by executive order and also questioned the rationale behind the change.

“It’s in statute that the department is the Department of Defense,” said Rep. Adam Smith, the ranking Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee, in an interview. “So if you’re going to change it, you have to change it in statute. You can’t do it by fiat. You can’t do it by executive order.”

The White House stipulated that “Department of War” is a “secondary title,” suggesting Congress need not be involved.

According to Trump’s executive order, Hegseth may use the Secretary of War title “in official correspondence, public communications, ceremonial contexts, and non-statutory documents within the executive branch.” The Pentagon may use “Department of War” in a similar fashion, Trump’s order notes, though the Department of Defense remains the title of the agency “until changed subsequently by the law.”

In business, this approach is called a DBA—”Doing Business As”—a common technique businesses use to operate under a name other than their official legal name. Google, the Internet search giant, is an example: The company is officially Alphabet Inc., but it does business under the Google name.

For the Pentagon, the heart of the debate over the department’s official name is what the new “secondary title” connotes. The change is a “nod to our proud heritage,” Chief Pentagon Spokesman Sean Parnell said in a statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine Sept. 6.

“[T]his change is essential because it reflects the Department’s core mission: winning wars,” wrote Parnell. “This has always been our mission, and while we hope for peace, we will prepare for war. Defense isn’t enough—we’ve got to be ready to strike and dominate our enemies.”

Trump made a similar point Sept. 5. “I think it sends a message of victory,” the president said, flanked by Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine. “We’re very strong. We’re much stronger than anyone would really understand.”

But critics in Congress said the new nomenclature reflects a narrow view of national security.

“Yes, we want to have the most lethal force in the world if we get into a conflict,” Smith said. “But what we decided after World War II is it was worth being strong enough to prevent the conflict in the first place.”

The current name for the Department of Defense dates back to 1949 and was directed by a Congressional amendment to a 1947 law. The Department of War ran the Army from 1789 until 1947, when the Air Force became a separate service and the Army, Navy, and Air Force were reorganized into a single department. After briefly calling the new department “the National Military Establishment,” Congress in 1949 changed the name to Department of Defense.

Smith said “defense” has a clear meaning: “’Peace through strength’ is what the Department of Defense means,” he said. “It means that you’re smart enough and strong enough so that people don’t attack you. That’s what defense is. I thought Trump was a ‘peace through strength’ guy, not a ‘war through war’ guy.”

Getting Congress to formally change the name of the Defense Department is politically and logistically challenging. Aside from convincing lawmakers, the sheer scale of the department makes such a change an expensive undertaking—buildings, passes, letterhead, and materiel throughout the world all bear the seal of the Department of Defense or reference the agency by that name.

The Pentagon said it could not provide an immediate cost estimate for such a change or even for the alterations that have already taken place, such as the replacement of signs around Hegseth’s office.

There is precedent and recent history about the cost of name changes, though. The Biden administration’s effort to rename military bases to remove the names of Civil War Confederate generals cost around $60 million, according to official accounts. Since taking office, Hegseth has largely restored the previous names, renaming the facilities after service members who bore similar names to the bases’ original namesakes.

“The cost estimate will fluctuate as we carry out President Trump’s directive to establish the Department of War’s name,” said a person who asked to be identified as a “War Department Official.” “We will have a clearer estimate to report at a later time.”

According to Trump’s executive order, Hegseth’s office has 60 days to provide the White House within “a recommendation on the actions required to permanently change the name of the Department of Defense to the Department of War.” Those actions “shall include the proposed legislative and executive actions necessary to accomplish this renaming.”

Republicans control both the House and the Senate. But some Republicans said the White House should be focusing on more substantial changes, especially regarding defense investment.

“If we call it the Dept. of War, we’d better equip the military to actually prevent and win wars,” Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky), the former Senate majority leader, in a statement on social media. “Can’t preserve American primacy if we’re unwilling to spend substantially more on our military than Carter or Biden. ‘Peace through strength’ requires investment, not just rebranding.”

In the meantime, the secondary branding goes on. The Pentagon rebranded many of its social media accounts and flooded social media with promotion of the change. As of 5 pm on Sept. 5, the official website for the Defense Department had become “war.gov.”