A new theater-level simulator is intended to help military and industry leaders gauge how platforms, weapons, and networks work together under fire—providing a chance to test out the systems behind Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2), the Pentagon’s sweeping plan to connect sensors and shooters across the globe.

Developed by Raytheon, the defense business unit of RTX, the Rapid Campaign Analysis and Demonstration Environment (RCADE) evaluates how an architecture of current or developing systems achieves campaign objectives, such as stalling an invasion by disabling a certain number of threats. The Air Force has similar programs such as Synthetic Theater Operations Research Model, or STORM, and the more recent Joint Simulation Environment, but RCADE is meant to run simulations at a much larger scale and deliver much faster results: from weeks or months to a few hours.

“We built it from the start to be agile, theater-scale, and flexible so that we could do airpower missions, Navy missions, and we can look at it all together in a joint, multi-domain battle,” George Blaha, principal tech fellow at Raytheon, told reporters at an Aug. 31 media event.

“Speed was an absolutely critical requirement … so we can get insights fast,” Blaha added. “And we cast a broad net with systems, so it’s not just ‘run one operations plan or battle and see what the results are,’ it’s dozens upon dozens of concepts for architectures, for red orders of battle, for red strategies, for blue strategies and so forth.”

It is also large-scale, with thousands of entities that can be plotted into a scenario. That could be especially useful for analysis at the planning and programming level.

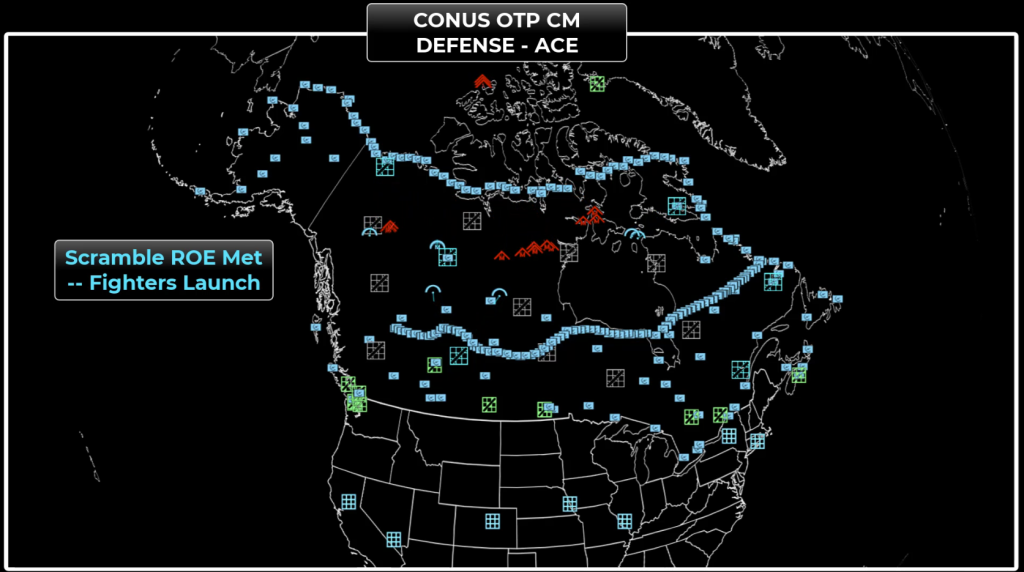

Blaha laid out an example where RCADE tested responses to enemy bombers and cruise missiles streaking south over the North Pole. In one run, defending U.S. and Canadian fighter jets took off from only military airfields, which limited their loiter time in the combat area and allowed several threats to reach the continental U.S. In a second run, fighters refueled at nearby civilian airfields—a move that would fall under the Air Force’s concept of Agile Combat Employment—boosting their loiter time and destroying 25 percent more threats as a result.

RCADE allows planners to compare such scenarios, as well as the effects of upgrades like over-the-horizon radar, longer-range air-to-air missiles, or improved command-and-control systems. The system can then display the results of hundreds of runs on a chart with metrics like percentage of cruise missiles destroyed on one axis and intercept distance from the continental U.S. on another.

“Many things can be varied in these simulations, everything from command and control behaviors to logistics behaviors, etc.,” Blaha said.

RCADE emerges at a time when RTX, the company recently known as Raytheon Technologies, wants to position itself as offering not just individual systems such as missiles and sensors, but also analysis of how those systems interact.

“Part of our role as a tier one prime is to understand mission priorities and evaluate architectures and scenarios in a way that informs the right decisions,” said Paul Ferraro, president of air power at Raytheon.

That mindset aligns with the Air Force’s own efforts to strengthen its “kill chain,” the sequence of steps needed to spot, identify, track, and destroy particular targets. Since the 1991 Gulf War, China has studied the Air Force kill chain and worked at ways to block or disable it, Heather Penney, senior resident fellow at the Mitchell Institute, wrote in a study on the topic published in May.

Brig. Gen. Luke C.G. Cropsey, the Air Force’s integrating program executive officer for command, control, communications, and battle management, plays a key role in the branch’s response.

“Architecture wins over products,” he said at an industry event in August. “In order to win the long term, you actually have to have an architecture that’s relatively agnostic to the individual nodes or agents that you have in that architecture.”

Ferraro emphasized that RCADE is not for sale. Instead, the company and the government agree to share data that fuels the simulator under the Cooperative Research and Development Agreement.

“This is not what I would call a Raytheon product,” he said. “We’re not selling this, not leasing it, not licensing it. This facilitates thinking, it facilitates engagement with customers, it informs our understanding of where we can contribute.”

Raytheon has already used RCADE to test systems that could enable JADC2. A June 7 press release described how the Army tested a data-collecting ground station in RCADE for a year before performing a three-month field test. The Tactical Intelligence Targeting Access Node, another RTX product, is designed to better connect space, sea, and land sensors to make long-range precision fire more accurate.

“The ability to simulate quickly and accurately shows that RTX engineers not only build and field the technologies it takes to pull off the JADC2 initiative—they can also help military customers figure out what they need and predict how it will all work together,” the release said.

While it will carry implications for airpower, what eventually became RCADE first began in 2016 as the Cross-Domain Maritime Surveillance and Targeting program, which modeled how the Navy could target enemy ships and submarines over vast distances in contested environments. The program grew over time as the Army, Air Force, and Office of the Secretary of Defense expressed interest. After years of development, RCADE now has “really hit a stride,” Blaha said.

There are still some areas for improvement. Blaha said RCADE is robust in the air, land, and maritime domains but has room to grow in space. He also wants to make it more capable for artificial intelligence and a field of machine learning called reinforcement learning, which could help automate some of the simulator’s functions. Ferraro indicated the simulator’s growing capabilities will allow for increasingly complex battle scenarios—for example, including large numbers of Combat Collaborative Aircraft and uncrewed underwater vehicles.

“When the threat is markedly changing, and the approach to combating that threat is markedly changing, this gives you a way of objectively analyzing various architectures, various ways of engaging in this evolving mission set,” he said.