Lt. Col. George Edward Hardy, the last of the Tuskegee Airmen who flew combat missions in World War II died Sept. 25, at the age of 100, in Sarasota, Fla. Hardy also went on to have combat service in both Korea and Vietnam.

Born in Philadelphia on June 8, 1925, Hardy was a good student who excelled in math and graduated high school, meeting the requirements when the Army opened up the flying specialty to black troops. He enlisted in the then-segregated U.S. Army in 1943 at the age of 17 and began training at Tuskegee Army Airfield, Ala., soon after. He won his wings and commission in September 1944, after which he trained as a fighter pilot in South Carolina. Following graduation from single-engine fighter training in early 1945, he was sent to Europe; one of only 355 black pilots to serve overseas during the war, and at 19, one of the youngest.

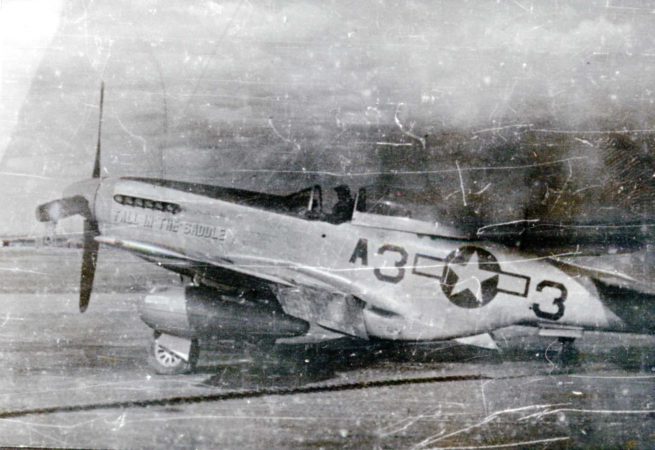

In the latter stages of the conflict, he flew the P-51D Lightning, flying 21 combat missions with the 99th Fighter Squadron, escorting bombers over Germany from bases in Italy. The 99th was much in demand from bomber groups because of its record in losing very few bombers to enemy fighter action. The unit decorated the tails of their aircraft with a red paint job to distinguish themselves, improve combat identification in group dogfights, and ensure that bomber crews knew who was protecting them. That gave them their nickname, the “Red Tails.”

Hardy also flew ground attack missions; strafing trains, trucks, boats, and other transportation targets. On one of these missions, he was hit by ground fire but was able to return to base.

After the war, Hardy returned to Tuskegee as an instructor pilot and remained with the Army Air Forces until Tuskegee closed in 1946. He enrolled in New York University and completed one term before being recalled to Active-duty in 1947, into the newly formed U.S. Air Force.

The Air Force was integrated in 1948. Hardy, who had been planning service as a maintenance officer—he specialized in radar and navigation systems—was permitted to train to fly bombers. He learned to fly the B-29, and when the Korean War came, flew with the 19th Bomb Group from their base at Okinawa, Japan, between 1950 and 1953. He faced discrimination during his time in bombers and was removed from his first mission because his commander did not approve of black pilots. He eventually flew 45 combat missions over Korea.

After Korea, he remained in the Air Force, earning a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a master’s in systems engineering from the Air Force Institute of Technology in 1957 and 1964, respectively. He continued to deal with prejudice, such as being denied on-base housing in Texas, but later said that as his rank increased, these kinds of problems diminished.

Into the 1960s, Hardy led maintenance units that worked on specialized electronic gear, and in 1966, he became a lieutenant colonel. In 1967, he returned to combat duty, piloting AC-119K gunships in the Vietnam War. He flew with the 18th Special Operation Squadron, attacking North Vietnamese supply routes in Laos and Cambodia, and along the Ho Chi Minh trail, using then-new infrared technology to see targets in the dark. He racked up 70 combat missions in the type.

He was one of a very few Tuskegee Airmen to have flown combat in three separate conflicts. His combat decorations included the Distinguished Flying Cross and 12 Air Medals.

In retirement, Hardy had a second career with GTE Corp., a telephone company in Massachusetts, where he worked for 18 years as a systems engineer and project manager. He also traveled the country recounting stories of the Tuskegee Airmen, and in 2024, accepted an award from the National World War II Museum on behalf of the group. The award recognized them for their patriotism and military achievement while also combatting domestic and institutional discrimination.

A P-51D restored with the markings of Hardy’s airplane—“Tall in the Saddle”—flies at airshows under the auspices of the Commemorative Air Force.