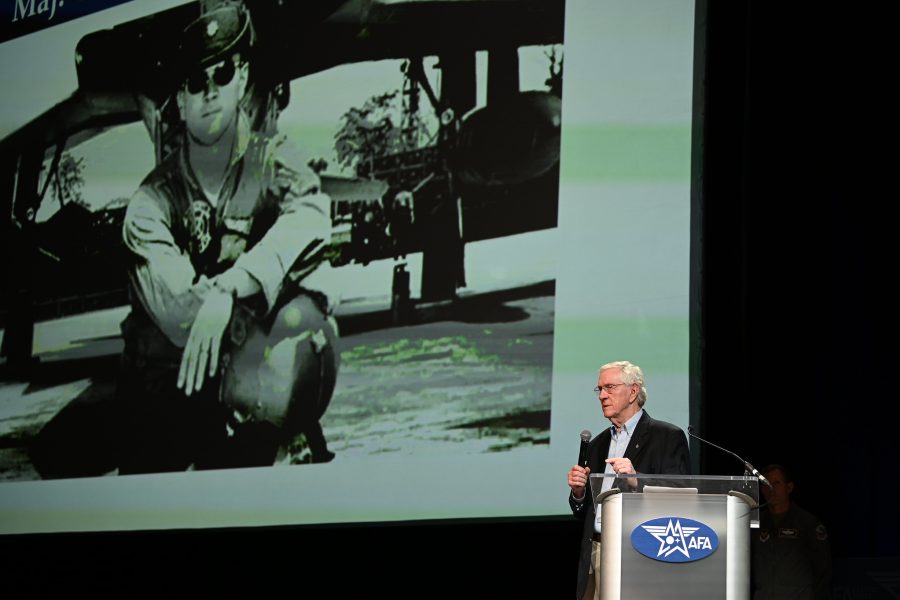

Lt. Col. Richard “Gene” Smith, who overcame five and a half years as a prisoner of war in the notorious Hanoi Hilton from 1967 until 1973, died Jan. 16. He was one day short of his 91st birthday.

“Gene Smith was an American hero, whose honor endured torture and who came home as a shining example of enduring selfless service,” said retired Lt. Gen. Burt Field, AFA’s President and CEO. “We celebrate a life well lived and mourn his loss.”

Smith was on his 33rd mission in the F-105 Thunderchief on Oct. 25, 1967, when he was redirected to strike the Paul Doumer Bridge over the Red River near Hanoi, North Vietnam. The bridge, built by the French and later renamed Long Biên Bridge, was a vital connection between Hanoi and the port of Haiphong.

“That’s the longest bridge in Southeast Asia [and] one of the most heavily defended positions in the history of aerial warfare,” he recalled in a 2017 Air Force interview. It was a beautiful day, visibility was 30 miles or better, but as they got close in, they came under heavy flak; he went into a 40-degree dive and descended to drop his load, and just as he pulled off, he felt the flak hit his aircraft.

“It sounded like someone hitting a wash tub. … Next thing I know the airplane tumbled,” he recalled.

In an interview with the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies recorded in 2022, Smith recalled telling himself, “I’m not going to die in this son-of-a-bitch,” and struggling to pull the ejection handle as his airplane tumbled through the sky. “And I started floating down, took inventory.”

He could see bone through a hole in his flight suit near his ankle. He could see people below him, and began to shed his gear: two radios and a service weapon. As soon as he hit the ground, a North Vietnamese soldier ripped two AK-47 rounds through his legs, the bullets miraculously tearing only flesh, not bones. “God had something else for me to do that day,” Smith recalled. “I’m a very lucky man.”

The people stripped him to his shorts, cutting his clothes off, hands wired together behind him, loaded on a truck, and taken to the infamous Hỏa Lò Prison, known today as the Hanoi Hilton. Smith had completed survival training in 1964, but that experience hadn’t really made a difference.

“Do you know when you start learning how to be a POW—if that ever happens to you?—it ain’t in survival school,” he said in the Mitchell interview. “It starts with your parents, or it starts with a coach, or it starts with a preacher, or a teacher, to instill in you what is right, and what America is all about. And you are very fortunate if you had a God-fearing family that exposed you to God. Because I can’t imagine going through that stuff and being in prison without God.”

The training he had received, such as giving no more information than name, rank, and serial number, went out the door in the first few seconds, Smith said. “They ask you what kind of airplane you were flying, and you say, ‘I can’t tell you that,’ and the next thing you know I was knocked all the way across the room. And then I was put in a ball, inspecting parts of my body that I’d never seen before, with my arms behind me and an iron bar with some cloth and some filings on it in my mouth, and they put a rope around it and just pulled tighter and tighter. And then he left, and I said, ‘Hell, maybe I’ll die.’”

But Smith did not give up. Enduring some 1,967 days in captivity, he learned to make up answers when interrogated, but also to remember those answers so he couldn’t be caught in a lie. Asked once who his commanding officer was, he offered “Bart Starr,” the star quarterback of the Green Bay Packers, whom Smith had known as a fellow ROTC cadet during their college days. The captors never caught on.

A friend and fellow POW, Lee Ellis, lived in the same camp and shared a cell with Smith for close to two years. They remained close with Smith in the decades after their incarceration.

“Gene was a great cellmate and has been a wonderful friend over the 52 years since we came home,” Ellis recalled. “He was tough and kind and a great example of how the Vietnam POWs resisted, survived, and returned with honor.”

Following his release in 1973, Smith became an instructor pilot for the 50th Flying Training Squadron at Columbus Air Force Base, Miss., beginning in November 1973. He held a series of jobs there before his final tour, as director of operations for the 14th Flying Training Wing. Smith retired from the Air Force in 1978.

For his exceptional bravery and leadership, Col. Smith was the recipient of two Purple Hearts, the Silver Star, the Distinguished Flying Cross with Valor, the Bronze Star with Valor, and the Air Medal.

Retired Maj. Gen. John Borling, who like Smith was shot down over North Vietnam and endured six-and-a-half years as a prisoner, paid tribute to his fellow Airman. “Gene Smith was a leader, during and after Vietnam, in two important groups,” Borling said. “The ‘never quits’ and the ‘keep marching’ gang. He attacked life to the utmost, no dress rehearsals required.”

Once back in civilian life, Smith was Executive Director of the Golden Triangle Regional Airport from 1979 to 1999. He was the volunteer National President of the Air Force Association from 1994 to 1996 and then AFA Chairman of the Board from September 1996 to September 1998. In those days, the day-to-day operations of the association were managed by a full-time executive director, and the President and Chairman were volunteer roles.

Richard E. “Gene” Smith was born in 1935 in Marks, Miss., and grew up in Tunica, Miss., where he made Eagle Scout at the age of 13. He was commissioned through the Air Force ROTC program at Mississippi State University on July 13, 1956, and two months later went on Active duty, completing Navigator Training in December 1957 and the Radar Intercept Officer Course in July 1958.

He was a Radar Intercept Officer on F-89 Scorpions and F-101B Voodoos with the 445th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Wurtsmith Air Force Base, Mich., from then until October 1961, then went to Undergraduate Pilot Training at Williams Air Force Base, Ariz., where he earned his pilot wings in October 1962. After completing F-102 Delta Dagger Combat Crew Training, Smith served 30 months with the 82nd Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Travis Air Force Base, Calif., and then two years with the 496th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Hahn Air Base, West Germany. He asked to fly F-4s but was turned down and assigned to fly F-105s.

Smith’s wife of 45 years, Rae, preceded him in death in 2003. He later remarried and is survived by his wife, Lynn, three children from his first marriage—Kelly Lucas, Rick Smith, and Stacy Kellum—and two stepdaughters—Stacey Miears and Erin Holland—along with 10 grandchildren and seven great grandchildren. Funeral services will be in West Point, Miss., on Jan. 23.