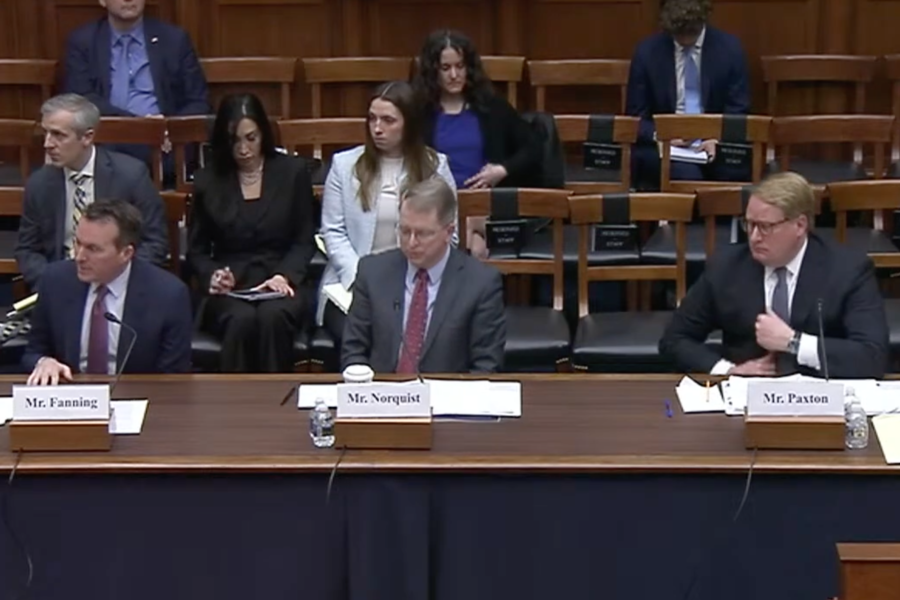

Rapidly supplying Ukraine with weapons is prompting calls to surge munitions production, but the defense industrial base can’t do it without contractual certainty and funding predictability from Congress, industry association leaders told the House Armed Services Committee on Feb. 8.

The companies comprising the defense industrial base—“DIB” for short—need “clear demand signals from Congress,” regulations that allow innovation, and action “at the speed of relevance,” Aerospace Industries Association president Eric Fanning told the HASC.

“Federal policy and investment in our national defense can be summed up in two words: unpredictable and inconsistent,” Fanning said.

Over the last 25 years, he noted, “Congress has passed more than 120 continuing resolutions instead of on-time appropriations bills.”

With continuing resolutions comes chronic uncertainty for companies on when or even if they will get paid in a timely manner or proceed to a new phase of development or production. That has deterred many companies from entering the business, driven others out, and deterred some from investing in capacity and long-lead items since they can’t predict when or whether the funding is coming, Fanning said.

The industry is also “still digging out from the effects of sequestration a decade ago,” which could “take years to unwind without a sense of urgency,” Fanning said.

Multiyear contracts, authorization for more long-lead materials purchases and a willingness to spend money on weapons that may not ever be used are the price of production capacity, he asserted.

The DIB has been optimized for peacetime needs, Fanning said, and so “excess capacity for surging is not … built into the system.”

David Norquist, head of the National Defense Industrial Association, said despite two consecutive National Defense Strategies declaring “the post-Cold War world is definitely over” and the need to prepare for military competition with China, “key industrial readiness indicators for great power competition are going in the wrong direction.”

For example, “we should expect the number of workers in the defense industrial base to be increasing. In 1985, the US had three million workers in the defense industry. In 2021, there were 1.1 million workers in the sector, and that number is remaining flat,” Norquist said.

The number of companies doing work in the defense sector has also declined, with some 17,000 companies having left the business in the last five years, he said.

“In particular, the Department of Defense recently estimated the number of small businesses participating in the defense industrial base has declined over 40 percent in the last decade,” he said. That’s likely related to the fact that “from 1985 to 2021, funding for national defense decreased from 5.8 percent to 3.2 percent” of the gross domestic product, and the Congressional Budget Office “projects a further decline to 2.7% by 2032,” he added.

Norquist’s statistics come from NDIA’s annual report on the health of the DIB, called “Warning Signs,” which was released the day of the hearing. It combined a survey of members with third-party data and analyses about the defense ecosystem. Most respondents said that despite “well-meaning” efforts to streamline defense work, most still find it “very hard” to work with the Pentagon, and that a key culprit is the long wait between winning a contract and actually getting it underway with money coming in the door. While big companies can usually ride that out, small businesses can’t.

“Those non-traditional industries … cannot afford the many regulatory barriers to entry along contracting timelines and the disruptive uncertainty with annual appropriations,” Norquist said.

He also noted that “in 13 of the last 14 years, we’ve had long continuing resolutions that specifically prevent new starts or increased production rates. These trends are not consistent with creating the defense industrial base required for great power competition.”

And while a “brittle” supply base is a “strategic vulnerability” a “resilient” one “is a powerful deterrent,” Norquist said, echoing recent remarks from William LaPlante, the Pentagon’s acquisition and sustainment chief.

“The condition of the industry today is not the result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but it’s successive decisions made over many years,” Fanning said.

He thanked the committee for authorities in recent years that can speed up some kinds of development and acquisition, but said the nation must “empower its workforce to move beyond a compliance culture to one that exercises existing flexibility.”

Witnesses also said they are struggling to attract and retain workforce, which Fanning called the “number one” issue among AIA members.

HASC chairman Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) said the war in Ukraine has “laid bare” the U.S.’s inability to surge weapons production, and he accused the Biden Administration of refusing “to use the authorities and resources Congress gave them last year to provide the necessary relief” from problems spurred by inflation, workforce shortages and bureaucracy.

Rogers and several other members also noted that the U.S. is dependent on China for a number of raw materials, such as rare Earth elements, that play a key role in many weapon systems. But Fanning said that while the aerospace industry can find other sources of the metals, “it’s the processing” of the ores that is largely monopolized by China.

Ranking member Adam Smith (D-Wash.) called the health of the industrial base “a growing … huge challenge” which “we were certainly aware of” before the war in Ukraine and the pandemic. The U.S. “suddenly found ourselves in desperate need of a lot more of certain production items” because of Ukraine “and discovered we did not have the surge capacity” necessary.

“We have heard consistently from our industrial partners, that they are not going to build a level of manufacturing capability necessary to produce stuff if they don’t know that someone’s going to buy it. … The cliché now is that ‘we need a demand signal,’ which basically means we need the government to promise [to] ‘pay us one way or another before we will make the investments to be able to make things quicker and faster.’ So we need to figure that out,” Smith said.

Smith said it won’t be possible to go into overdrive production of every defense article, as “we just do not have the resources … to be able to prepare for every conceivable contingency,” and the private sector won’t make the investment “on a wish and a promise.”

The situation is the result of China throughout the “late 1990s and early 2000s … [being] where you went to make stuff” without having to pay “huge labor costs [and] certainly no environmental regulations. It was cheap. It was easy.” But now, he said, “we are beginning to diversify in a bipartisan way.”

He added that the U.S. can’t meet this challenge on its own, “and I know people don’t like hearing that,” but the capacity situation will require efforts from U.S. allies and partners as well. As much as “people want America to be independent … that’s not the way the global economy works. We need to increase our capacity, absolutely. But we also need to work with trusted partners.”

Fixing the problem will take time, Fanning said, particularly the workforce issue and “building the ecosystem” of the industrial base to be more responsive and resilient.

Norquist said the industry needs “more than a signal” but “a contract” on a multiyear basis, and that will provide all the incentive necessary. Industry wants to “get ahead” of the contract, though, so it can lay in the workforce and infrastructure to compete well for work, so he urged the Pentagon and Congress to be direct in saying what they want and to then back it up with the money.