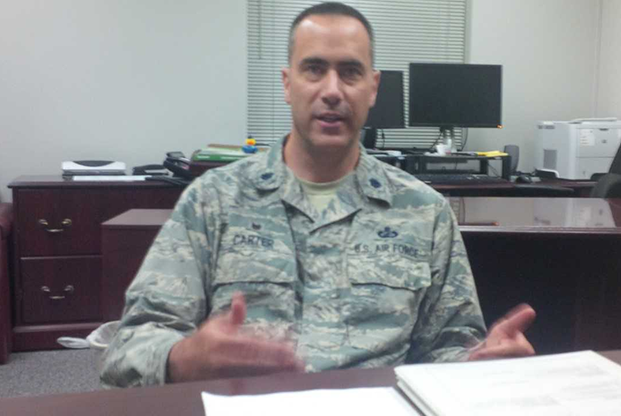

AF Lt. Col John Carter, commander of the 332nd Training Squadron, DLIELC, outlines the changes at the Defense Language Institute English Language Center at JBSA Lackland because of shifts in the international situation and US policies. Air Force Magazine photo by Steve Hirsch.

JBSA-LACKLAND, Texas — The curriculum and the makeup of the student body at the Defense Language Institute English Language Center here have evolved in recent years as a consequence of shifts in the international situation and US policies.

Air Force Lt. Col. John Carter, commander of the 332nd Training Squadron and dean of academics at the language center, outlined the changes in an interview here Wednesday. The center is the Pentagon’s hub for teaching English to foreign military officers who need to become proficient in the English language, for example, to be able to be trained on US military equipment. It also serves US service members who need to improve their language skills, such as Puerto Rican recruits, those who are green card holders, and for those who speak English as a second language. The school teaches both here and in other locations, such as Florida, Puerto Rico, Japan, and Qatar.

Increased reliance on coalitions means students must know terms and phrases the US military uses and how the US military operates.

“The military decision-making process is something unique to the US military,” he said, so terms like “end state” and “operational environment,” and “the way we plan and execute an operation” are things the school is trying to introduce to students, he said.

In addition, the last 20 years have produced new terms, such as “global war on terrorism.”

Carter said other shifts, including those to US policy, have required changes in the way English to the students.

“As we wake up one morning and we’re friends with some countries, and the next morning we may not be so friendly, that might change what we put into our curriculum,” he said.

For example, he said, earlier curricular might refer to “enemy” MiGs. “Well, today if you look across the world, there are still a lot of countries using and flying the MiG who are our allies and NATO partners.”

Those MiGs might be old and those countries might be trying to modernize, “but for us to identify a MiG as an enemy may not be politically correct or accurate,” he said.

The school must also accommodate technological changes students deal with, he said, such as pilots’ switch from paper and maps to digital devices, as the school’s specialized English courses deal with subjects ranging from medical topics to explosive ordnance disposal to diving to pilot training.

For pilot training alone, he said, “we have army helicopter pilots, we have fighter pilots, we have heavy pilots, all kinds,” so, “if you look at the way the United States instructs those specialties, there have been a lot of changes to the way we teach, just based upon technological changes.”

The student body has also changed since the school started in 1954, having started with Vietnamese and Iranian students. Now, he said, there are a lot of students from Saudi Arabia, for example, but fewer European students than before because more Europeans speak English and the Europeans also do their own military language training. Egypt and Japan also are becoming self-sufficient in teaching their military members English.

The school has increased interest, on the other hand from Vietnam, whose armed forces want to set up some of the school’s training sites at their bases there.

The school is also seeing rising interest from African countries, which Carter attributed to an interest in building their air forces. Though these countries may not have an air force or a military yet, they are building them and are starting to get equipment, and as such could be constituting a new market for the school, added Carter.