Air Force Reveals Range and Inventory Goals for F-47, CCAs

By John A. Tirpak

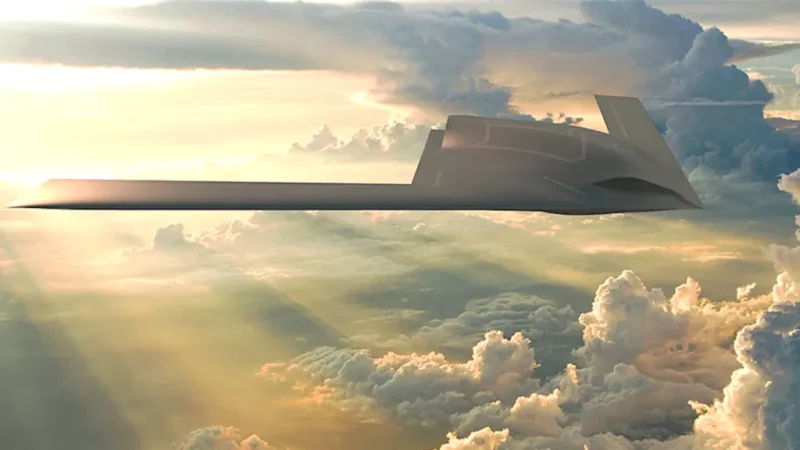

The F-47 Next-Generation Air Dominance fighter will have a combat radius greater than 1,000 miles—nearly double that of the F-22—and the Air Force plans to acquire more than 185 of them, Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin revealed in May.

Alongside the F-47, the first Collaborative Combat Aircraft, dubbed Increment 1, will have a combat radius of more than 700 miles, greater than both the F-22 and F-35. The Air Force plans to acquire more than 1,000 of the autonomous drones.

“Our [Air Force] will continue to be the world’s best example of speed, agility, and lethality,” Allvin wrote on social media. “Modernization means fielding a collection of assets that provide unique dilemmas for adversaries—matching capabilities to threats—while keeping us on the right side of the cost curve.”

The revelations came in a graphic accompanying Allvin’s post, which shows the F-15E/EX, F-16, F-22, F-35, F-47, and the two CCAs—the YFQ-42A and YFQ-44A. Each is labeled with the date of their entry into operational service, combat radius, speed, and a very basic description of their stealth capabilities. The graphic indicates a later entry for the CCAs than anticipated.

While the F-47’s 1,000-mile combat radius is impressive, it falls short of what would be needed to take off from Guam and reach mainland China or Taiwan using only internal fuel. Aerial refueling would be necessary to extend its reach, although fewer tankings would be needed.

With a combat radius of 700 nautical miles, the CCAs would be able to fly out ahead of the F-22 and F-35.

While former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said at AFA’s 2023 Air Warfare Symposium that 200 F-47s was the acquisition target, the graphic mentioned “185+”, revealing that the Air Force now plans the F-47 to be a virtual one-for-one replacement for the F-22, of which there are also 185. Cost is undoubtedly a factor: Estimates run as high as $300 million per copy.

Both the F-47 and the CCAs were labeled as planned to enter service between 2025 and 2029. The F-47’s maximum speed was labeled as being “Mach 2+,” less than the F-15, which was rated at Mach 2.5.

The graphic offered a rudimentary assessment of each aircraft’s observability: The F-35 and CCAs were described as “stealth” aircraft, the F-22 was described as “Stealth+” and the F-47 as “Stealth ++.”

The F-22’s combat radius was described as 590 nautical miles, above the 470 nm more commonly reported. Combat radius, however, is a fungible figure, dependent on the flight profile to the target, and whether the aircraft is expected to perform aggressive combat maneuvers along the way. The Air Force’s official F-22 fact sheet doesn’t provide a combat radius, but the figure in Allvin’s graphic suggests a range augmented by external fuel tanks.

To be “stealth ++” though, it’s likely that the F-47’s range does not count any external fuel tanks, which would increase its radar signature.

The graphic also confirmed that the two CCAs have a primary mission of “air superiority,” meaning they will largely serve as missile carriers for the fifth-generation crewed fighters they will escort into battle, expanding the number of shots each crewed fighter can take per sortie.

The Air Force and its CCA contractors Anduril Industries and General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, have been promoting speed in the CCA program, and have said the two aircraft will fly “this summer.” However, the Air Force said in response to a query that Anduril and General Atomics “will fly their production-representative test aircraft by the end of the calendar year,” indicating a possible delay of three to five months.

It’s not clear if the inventory objective of 1,000 CCAs in the graphic refers to the Increment 1 aircraft now in ground testing, or CCAs of all increments. The Air Force has said it will launch Increment 2 next year, and service leaders have suggested that it could be a less sophisticated and less costly aircraft than in Increment 1. Senior Air Force officials have referred to future iterations known as Increment 3 and 4 without providing further details.

JetZero: Blended-Wing-Body Tanker is ‘Game-Changer’

By David Roza

When the last Air Force KC-10 tanker flew its final sortie in September 2024, Airmen mourned the loss of an aircraft that could haul a “staggering” amount of gas and nearly as much cargo as a C-17.

But a new aircraft under development in California could fill that void with a novel design that could fly even more gas even farther afield than anything in today’s fleet.

Aerospace startup JetZero’s Z4 is a blended-wing-body aircraft that its makers say will use 50 percent less fuel than conventional tube-and-wing designs. For tankers, that means fueling more aircraft at longer range. Its lift property also means the Z4 can use shorter runways, and its unusual cabin can accommodate taller pallets of cargo.

“The capability that the Z4 brings, for the tanker mission specifically, is a quantum leap,” said Brian Tighe, a retired B-52 pilot who is now executive vice president of the aviation consulting company Allied Defense Services International, a division of Consolidated Air Support Systems (CASS).

CASS helped JetZero refine its proposal to the Air Force, which in 2023 announced a $235 million contract to fly a full-scale commercial demonstrator in 2027. Nearly two years and many subscale demonstrator flights later, JetZero officials expect to deliver on schedule.

The full-scale fuel tanks are built, the cockpit tooling is complete, and a wing test article is being evaluated, said JetZero’s head of engineering, Florentina Viscotchi.

Nate Metzler, head of strategic programs and partnerships at JetZero, said a potential KC-Z4 could carry enough gas after 4,000 nautical miles (about the distance from Joint Base Pearl-Harbor Hickam, Hawaii, to 500 miles off Taiwan) to offload about 10,000 pounds each to six F-35s, compared to just one for a KC-46 flying the same mission.

“You could sit in a refueling track for 45 minutes as the F-35s fill up and go on to do their work,” Metzler said. “And then the Z4 could go back to base 4,000 miles and land without having to refuel.”

Running on Empty

When it comes to tankers, the Air Force is running out of gas. The KC-135 makes up the bulk of the tanker fleet, but the sexagenarian aircraft will soon be too difficult to keep flying.

“Over the next decade, the aging KC-135 aircraft fleet will be an ever-increasing readiness concern,” Gen. Randall Reed, the head of U.S. Transportation Command, wrote in a statement for Congress on March 5. The air refueling fleet, he added, is “the most stressed deployment, sustainment, and combat capability,” as well as “the lifeblood of the joint force’s ability to deploy forces.”

The new KC-46 brings fresh iron, but the Air Force has not ordered enough of them to replace every KC-135. Air Mobility Command is completing an analysis of alternatives for the Next-Generation Air refueling System (NGAS). Air Force officials previously said the performance of the blended-wing body would inform that work, and former Air Force pilots believe the Z4 could be revolutionary.

“This is the game-changer,” said retired Maj. Gen. Erich Novak, a former KC-135 and KC-10 pilot who is now chief financial officer at CASS. “Energy efficiency, payload, range, those are the brass rings for tanker aircraft.”

AFRL, Bets on Hybrid-Electric Drone From General Atomics to Replace U-2

By John A. Tirpak

Drone manufacturer General Atomics (GA) is developing a new autonomous, stealthy, ultra-long-endurance reconnaissance and strike platform for the Air Force under a $99.3 million Air Force Research Laboratory contract awarded May 27.

The aircraft will be powered by “hybrid-electric propulsion” using a ducted fan. The Air Force dubbed the program GHOST, but did not explain the acronym. The sole-source contract is a cost-plus-fixed-fee deal, and GA is to complete work by August 2028.

The Air Force plans to retire the venerable U-2 Dragon Lady, a crewed ISR aircraft, beginning in 2026. The new GHOST could fill that requirement. At one time, the U-2 was to have been replaced by the uncrewed RQ-4 Global Hawk, but USAF has been retiring those aircraft in recent years and plans to retire all variants by the end of 2027. The Air Force is believed to be operating an ultra-stealthy RQ-180 long-range ISR platform built by Northrop Grumman, but has repeatedly declined to comment on that program.

Neither the U-2 nor the RQ-4 ever had a kinetic strike mission, while GHOST seems slated to have that capability. GA had worked on an “MQ-X” program—a stealth version of the MQ-9 Reaper—something the Air Force has pulled in and out of its budget for at least 10 years.

General Atomics showed a photo of a flying-wing-type ISR aircraft at its booth at the 2022 AFA Air, Space & Cyber conference. GA Aeronautical Systems President David Alexander, in two appearances on the “Tomorrow’s World Today” podcast that year, said GA was working on a “game-changing” aircraft using ducted fan technology employing diesel fuel.

The flying-wing design is “not a ‘me too’ for us,” Alexander said, but a new concept that could expand the range of an aircraft of the size and weight of the company’s MQ-9 Reaper to “triple the endurance.”

The Reaper’s publicly acknowledged endurance is about 27 hours; tripling it would extend beyond 80 hours.

The hybrid electric ducted fan engine “will have three times the endurance of a buried turbofan” with “the same size and weight” of the MQ-9, Alexander said in one of the podcasts. “It’s highly efficient.”

Hybrid-electric motors save fuel and extend range by combining the benefits of powered combustion with batteries. They also run quieter than typical engines, and, combined with diffusive exhausts, can reduce infrared signature. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency announced last year that it had assigned the nomenclature XRQ-73 to an autonomous flying-wing reconnaissance aircraft, which it touted as offering “extra-quiet” propulsion. That aircraft was given the name SHEPARD, for Series Hybrid Electric Propulsion AiR Demonstration.

A very similar concept to what GA displayed at its 2022 ASC booth is part of its “Gambit” scheme—four different-planform autonomous aircraft that can share a common chassis consisting of an engine, processors and landing gear. The company describes Gambit’s flying-wing element as an “ultra-long-endurance, multi-domain sensing, persistent battlespace awareness” platform.

Netflix’ Thunderbirds Documentary Puts Viewers in the Pilot’s Seat

By David Roza

A new Netflix documentary about the Air Force’s Thunderbirds aerial demonstration team “wonderfully” captures the highs and lows of life on the air show circuit, where extraordinary is the norm, and anything less puts lives at risk.

“Watching it brought back all of those wonderful feelings of being on point with five other jets tucked in neatly right underneath my wings,” said retired Col. John “JV” Venable, who commanded the team from 2000 to 2001. Venable is now a senior resident fellow for airpower studies at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

“Air Force Elite: Thunderbirds,” The 91-minute documentary follows the 2023 Thunderbirds team through winter training at Spaceport America, deep in the desert of southern New Mexico. Six F-16 pilots, including three newcomers, come together to put on a demo that goes against nearly every safety instinct drilled into them as tactical fighter pilots.

“Flying aerobatics is just not something we train for,” said Lt. Col. Justin “Astro” Elliott, the team commander at the time. “You have to divorce yourself from your survival instincts to fly this demonstration.”

To bring that to life, the film focuses on Maj. Jake “Primo” Impellizzeri, who flew the right wing as Thunderbird 3. Impellizzeri had previously flown on the single-jet Pacific Air Forces F-16 demonstration team, but much of the film centers on his struggle to master the Thunderbirds’ “high bomb burst” maneuver.

The jet on the right wing has to rejoin the four-ship formation after the upward “burst,” a punishing move that requires pinpoint precision at high speeds and almost seven times the force of gravity.

“It’s the most frustrating thing I’ve ever done,” says Impellizzeri in the film, after missing the rejoin again. Retired Maj. Michelle “Mace” Curran, who flew with the Thunderbirds from 2019 to 2021, understands just what that means.

“Everyone who shows up is really excited that they were chosen to be part of this amazing organization, and then they go through their own struggle trying to learn their new job in this new place with new standards that are very high,” she told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “Those feelings that Primo had of ‘am I the right person for this job?’ and feeling like a bit of an impostor, every person on the team goes through that in a different way.”

Curran recalled her first time flying the show in the back of the two-seat F-16.

“I was flinching left and right, like, ‘That jet is so close to us, we’re about to hit him, this is it, this is how I die,’” she said.

The documentary’s breathtaking cockpit footage, frequently shows the Earth rising to meet viewers at incredible speed, helping viewers get that sense firsthand. Thunderbird pilots fly twice a day, five days a week, throughout the winter training season to develop the muscle memory needed to do their job. Pilots progressively build their skills, starting far from the ground and in pairs before switching to a looser diamond formation, then gradually move closer to each other and the ground as they improve.

By the end of the season, “it becomes almost like a flow state that you’re in. It just feels like second nature,” Curran said. “It’s really cool to experience that, and you trust each other at such an extreme level.”

Overseeing it all is Thunderbird 1, who—depending on the season—must learn in parallel not only how to fly an air show, but also how to command it. The story’s second main character is Elliott, who the rest of the formation can follow right into the ground if he isn’t careful.

“The wingmen don’t know where the ground and the sky are. They only know where the boss is,” air show announcer Rob Reider told Netflix. “They trust him without reservation.”

It was the same way when Venable commanded the team in the early 2000s. “Any time the formation was tucked underneath my wing … the guys are so fixated on my aircraft that they really can’t check their peripherals in time to save their own lives,” he said. “It’s up to me and the trust that I built, just like it was in the movie with Astro.”

When things go wrong, it’s deadly. Maj. Stephen “Cajun” Del Bagno died in training on April 4, 2018, after losing consciousness due to G-forces, doing the same rejoin maneuver Primo struggled with in the documentary. Del Bagno’s parents share their story in the film.

“I cannot overemphasize how much that crash shook the team,” said Curran, who had been stationed with Del Bagno in a prior assignment and who got to know his parents well during her show seasons. “I can’t imagine [Netflix] doing this documentary without telling his story, because he was really an exceptional person.”

Del Bagno’s death, plus the cancellation of shows during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, gave then-Thunderbird 1 Lt. Col. John “Brick” Caldwell the time and focus to rethink the performance routine. The new demonstration brought jets closer to each other, which counterintuitively made the show look better and fly safer by focusing the pilots’ attention, experts said in the documentary.

Replacing Caldwell required someone special: “Somebody who’s got the tactical sense of like, a weapons school graduate, the physics and the aerodynamics sense of a test pilot school graduate,” says then-Air Combat Command boss Gen. Mark Kelly in the documentary. “Those people don’t exist. Well, one existed.”

That was Elliott, who gave up a childhood dream of becoming an astronaut to complete the Thunderbirds’ transformation.

Taking the role also meant missing his family nearly every weekend for two years straight. “I think anyone in this position would question, ‘Am I doing damage here that I can’t recover from?’” Elliott said. “I hope I’m right, when I say, ‘No, we’re going to be just fine.’”

Elliott’s sacrifice, the impact of Del Bagno’s death, and Primo’s journey makes “Air Force Elite: Thunderbirds” more than remarkable airplane footage; it really is a compelling human story.

Curran’s only regret? That the film didn’t spend more time with the rest of the team.

“They mentioned several times that the team is 135 people, and each of them is on their own version of Primo’s journey,” she said. The team’s maintainers get only a brief shoutout, where they describe working all night in the cold desert to fix a broken servo on an F-16’s right horizontal stabilizer.

“You’re tired, you’re cold, you’re hungry, you just want to go home and go to bed,” said Crew Chief Staff Sgt. Xavier Knapp. “But if we want that jet to fly tomorrow, it’s going to fly tomorrow.”

Venable and Curran were excited that the film might reach a wide, public audience through Netflix. “I’ve watched it once, and I’ll watch it several more times,” Venable said. “It is wonderful and well worth the time to see and see again.”

Hegseth Cuts DOD’s Test Enterprise; Critics Fear Loss of ‘Honest Broker’

By John A. Tirpak

The Pentagon will drastically reduce the staff and budget of the Director of Operational Test and Evaluation, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced in May. The move is intended to get weapons to the field more quickly but at the cost of removing what many consider a critical layer of independent oversight.

DOT&E performs “redundant, nonessential, non-statutory functions … that do not support agility or resource efficiency,” Hegseth’s order said. Citing a “comprehensive internal review,” he said the agency is a drag on “our ability to rapidly and effectively deploy the best systems to the warfighter.”

The order slashed staff from about 94 to 46, leaving 30 civilians, 15 uniformed personnel and a Senior Executive Service leader. All told, Hegseth said, the cuts will save about $300 million annually, mostly by cutting contract staff and support.

Much of that money funds contracts with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) and MITRE Corp., federally funded research-and-development corporations that provide contract engineering support. Defense contractor CACI and academic institutions including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are also agency contractors.

Greg Zacharias, who was chief scientist at DOT&E from 2018 to 2021, told Air & Space Forces Magazine that the cuts involve “maybe 250 testers who are the cream of the crop”—talent and expertise he called vital to ensuring new weapons work as advertised.

“We’re looking at an 80 percent reduction in manpower,” said Zacharias, bluntly adding: “They will unquestionably fail at their mission.”

Zacharias said DOD’s plans to field new weapons programs like the Golden Dome missile defense system on aggressive timelines are driving the push to cut testing. “No testers, no failures,” Zacharias said.

DOT&E’s contributions include designing tests, lending design expertise, and training the testers themselves. It “oversees that a test was designed correctly, was actually executed correctly, and then the analysis results are supported by the data,” Zacharias said.

William LaPlante, who was undersecretary of defense for acquisition and sustainment during the Biden administration, said DOT&E is uniquely valuable.

“You need that independent view,” he said. While the services have their own test organizations, DOT&E’s role in overseeing the design of test plans ensures neither the military services nor their contractors cut corners or game the system. “You need to keep people honest,” LaPlante said. “You need those checks and balances … a common interpretation of the facts. DOT&E really pays attention, and people really pay attention to what they say.”

The Air Force Operational Test and Evaluation Center, which does the bulk of Air Force testing, may not “have the clout … if something needs work, to get it fixed,” LaPlante said. “DOT&E puts out that annual report, the press picks it up, Congress pays attention to it.”

Former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall agreed that formulating the Test & Evaluation Master Plan is among DOT&E’s “primary values.” But he also said, “their scope expanded over the years and scaling it back might make some sense,” acknowledging that while DOT&E “is value-added … it is burdensome.”

DOT&E reports provide a counterpoint to service claims about how well their programs are progressing, Kendall said, and their message gets heard: “They’re seen as an honest broker on the Hill.”

Indeed, Sen. Jack Reed (D-R.I.), ranking member on the Senate Armed Services Committee, lashed out against the move. “Secretary Hegseth’s decision to gut the Pentagon’s Director of Operational Test and Evaluation office is reckless and damaging to military accountability and oversight,” Reed said in a release. Reducing DOT&E to “a skeleton crew and limited contractor backing,” he added, means the agency cannot provide “adequate oversight for critical military programs, risking operational readiness and taxpayer dollars.”