Space Force Looks Beyond Earth’s Orbits

By Courtney Albon

The Space Force’s small size has limited its capacity to consider what role it will play in future operations on and around the moon. That needs to change, according to Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. Shawn Bratton.

The service is in the midst of distilling its future operating needs into an “objective force” that lays out what platforms, support structures, and manpower will be required to maintain space superiority between now and 2040. That document should be released sometime this year, and during a Jan. 21 event at Johns Hopkins University’s Bloomberg Center in Washington, D.C., Bratton said a plan for cislunar operations needs to be part of that discussion.

“We’re thinking about that a little bit, but we should be thinking about it a lot right now,” he said. “Some of that is capacity; we’re small, and we’re focused on first things first. … But we should be thinking about cislunar.”

Much of the U.S. government’s moon ambitions have centered on NASA and its Artemis program. The agency plans to launch a crewed lunar landing mission in mid-2027 as well as several moon-

orbiting missions in the meantime. The first of those is slated to launch in February and will send four astronauts on a 10-day flight around the moon.

The Defense Department and the Intelligence Community have largely focused their attention on developing domain awareness and navigation capabilities to better understand cislunar space, the vast region between geosynchronous orbit and the lunar surface. The Space Force’s Oracle program, run by the Air Force Research Lab, plans to launch several space situational awareness satellites in the coming years. And the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency is working with the Space Force and NASA to create the mapping infrastructure for a GPS-like capability to support lunar navigation.

Bratton said the Space Force should expand its cislunar planning and he challenged the companies supporting NASA and pursuing their own commercial moon endeavors to con-sider how DOD could leverage their work.

“There are a lot of companies going to the moon right now,” he said. “What is the national security implication of your work? And what do you need from the Space Force? Start to demand that, or at least help us think through that.”

AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, argued in a 2024 report, that cislunar space is akin to the first island chain in the Pacific—strategically relevant to securing space for all. “DOD must establish an infrastructure for the cislunar regime, extending the types of services and capabilities currently in operation closer to Earth, such as space domain awareness, high-bandwidth communications, and cislunar navigation technologies,” the report argued.

BEYOND CISLUNAR

Besides cislunar operations, Bratton highlighted two other areas the Space Force’s objective force will need to address: satellite refueling and the implications of Guardians one day operating in orbit.

The service has for years been weighing how to invest in refueling capabilities, and Bratton said it’s still having active discussions about whether the military should lead the way or lean on industry.

“We have a really good hand on the cost curve of when it becomes economically beneficial to start refueling a constellation,” he said. “It has to do with the size of the constellation and the cost of each spacecraft. And so, we’re getting really good information on when it makes sense for economic reasons. I don’t know that that’s the exact same thing as military advantage.”

The Space Force and other DOD agencies have four missions slated to launch this year to demonstrate satellite refueling, servicing, and repair capabilities that will inform the service’s ongoing analysis.

In contrast to refueling and mobility, USSF talks very little about when and if it may one day need to have Guardians operating in space. While there are “some corners where people are writing papers about it,” Bratton said there should be more open discussion within the service.

“Where are we going with that? I don’t have the answer to that,” he said. “It would be tragic if that didn’t happen someday. Is that day 2030, 2040, 2050? I don’t know. We owe work on that.

Space Force Activates SOUTHCOM Component

By Greg Hadley

The Space Force celebrated the activation of its component under U.S. Southern Command in a Jan. 21 ceremony—though it did reveal the organization became operational Dec. 1, 2025, presumably meaning it contributed to Operation Absolute Resolve, the Jan. 3 mission to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and take him to the U.S. for trial.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman, Air Force Undersecretary Matthew Lohmeier, and acting SOUTHCOM Commander Air Force Lt. Gen. Evan L. Pettus were all on hand for the activation ceremony at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz. Col. Brandon P. Alford leads the new organization, Space Forces Southern, which will be co-located alongside Air Forces Southern.

“This new organization reaffirms our commitment to address local threats of all shapes and sizes, ranging from malign state actors to violent extremist organizations and to transnational criminal organizations,” Saltzman said at the ceremony. “Space Forces Southern will continue to be a force for good in the

region, using space to maintain peace and stability, and defend the homeland.”

Components serve as organizational links between the services and combatant commands, presenting forces for operations.

In late 2022, the Space Force made a point of establishing its first component under U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, reflecting the strategic focus on the “pacing challenge” of China. Since then, the service has established components for sub-unified combatant commands in Korea and Japan, a component for

U.S. Central Command, and a combined component for U.S. European Command and U.S. Africa Command.

Plans have been in the works to create Space Forces Southern for some time now, but they likely gained new urgency after the release of the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy in November, which places a greater priority on the Western Hemisphere.

“The activation of Space Forces Southern affirms a simple and powerful idea: we are one hemisphere, stronger together,” Alford said at the ceremony. “Bound together by geography, values, and a shared future above us—connected by shared challenges and shared opportunity.”

U.S. Southern Command as a whole has seen a major increase in activity in recent months as part of Operation Southern Spear, the mission to combat drug trafficking and pressure the regime of Maduro, and Operation Absolute Resolve.

Space assets have played a role in all this; according to photos taken Dec. 4 and released a few weeks later, Guardians deployed to Puerto Rico during the buildup of U.S. military forces in the Caribbean. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Dan Caine specifically noted that U.S. Space Command contributed to Operation Absolute Resolve. He did not explain how, exactly, and officials have largely declined to elaborate, citing operational security. “Space-based capabilities such as Positioning, Navigation and Timing and satellite communications are foundational to all modern military activities. As such, to protect the Joint Force from space-enabled attack and ensure their freedom of movement, U.S. Space Command possesses the means and willingness to employ combat-credible capabilities that deter and counter our opponents and project power in all warfighting domains,” a SPACECOM spokesperson previously told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Saltzman also referenced recent events in South America and the Caribbean.

“As we clearly saw in recent operations in the SOUTHCOM [area of responsibility], without space, kill chains don’t close, our strategic advantage evaporates, and we can’t complete our joint missions,” Saltzman said.

While SPACECOM is responsible for providing effects from orbit, it still needs to coordinate with SOUTHCOM and Space Forces Southern.

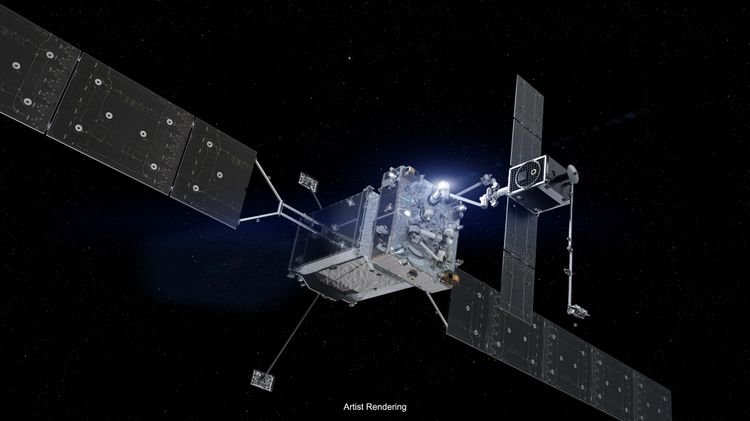

On-Orbit Satellite Servicing—4 Missions in 2026

By Shaun Waterman

Four satellite missions will launch in the coming year to demonstrate on-orbit refueling, servicing, and repair capabilities to extend the lives of military satellites. Funded by different Department of Defense entities, each will also entail commercial efforts.

The missions are critical for the Space Force, according to officials and industry executives, which sees dynamic space operations—the ability to maneuver satellites as needed to either approach or avoid adversary space systems—as crucial to its ability to fight and win a space conflict. Without that

ability, every maneuver that expends a satellite’s fuel effectively shortens its life.

China, which operates a smaller space fleet, appears a step ahead in this regard. In June, two Chinese satellites docked in geosynchronous Earth orbit, performing the first-ever on-orbit refueling mission in GEO. The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) demonstrated on-orbit years ago with satellites in low-Earth orbit and special refueling equipment in 2007. But standards for refueling satellites have changed little since then.

The Space Force is betting the private sector can provide these capabilities, and all four missions scheduled for 2026 aim to demonstrate not just the technology but the business case, as well.

The four planned operations will all be in GEO, more than 22,000 miles above the Earth’s surface. Operating from a fixed point in the sky relative to the ground, GEO offers consistent communications and coverage, with more than 500 high-end, large satellites performing crucial telecommunications and broadcasting functions. These highly engineered spacecraft, developed at great expense and intended to have a useful life measured in decades for both government and commercial customers, are prime opportunities for life-extending services.

Rob Hauge, president of SpaceLogistics, a Northrop Grumman company, said the opportunity is huge. “Every year about 10 to 20 reach their end of life because they run out of fuel,” he said.

Without having been designed to take on additional fuel in flight, the question becomes how to retrofit that capability to an existing system. One solution: Add a new component to the existing satellite bus, a so-called “Mission Extension Pod (MEP).”

SpaceLogistics has developed its own Mission Robotic Vehicle (MRV) to bridge service satellites in GEO. Equipped with an autonomous robot arm developed by the Naval Research Laboratory, and funded with DARPA money, SpaceLogistics will launch an MRV next year to demonstrate Robotic Servicing of Geosynchronous Satellites (RSGS). Under that program, MRV will recover a satellite and reposition it in orbit, and then, using its robotic arm, capture and install a Mission Extension Pod, attaching it to the existing satellite and giving the satellite a new lease on life, with freedom to maneuver.

Hauge said once in space, the MRV can “do that again and again and again,” extending the profitable life of aging satellites. The MRV can also be used for “anomaly resolution,” said James Shoemaker, DARPA program manager for RSGS. In other words: it can repair systems.

About three times a year, something unknown goes wrong with a satellite in GEO, Shoemaker said. “You’ll have a partial deployment of a solar array where, perhaps the hinge just gets a little stuck,” or an antenna deployment doesn’t go as planned, he said. Operators on the ground can try various measures to resolve the problem, but as they “try to rock the satellite” to shake a stuck part loose, they also are expending some of its limited fuel. Often, when something goes wrong, operators are basically in the dark, Shoemaker said. MRV can maneuver near the satellite to provide “a picture and a close inspection of what exactly is wrong,” making it “a lot easier for them to figure out a solution.” It’s notable, Shoemaker said, that RSGS is the second DARPA program to demonstrate on-orbit refueling and servicing capabilities.

“Typically, DARPA does things first to prove you can do them, and then we hand them off and start doing something different,” he told Air & Space Forces Magazine. Revisiting a challenge is “somewhat unusual,” he said, but the earlier Orbital Express in 2007 was in LEO, where the economics of servicing and repair are very different. Satellites in LEO are typically smaller and less costly, making repair not necessarily worth the cost.

In GEO, where satellites operate in a single orbital plane above the equator, the satellites are larger and more costly, with much wider areas of coverage. And in GEO, Shoemaker explained, “changing your angle of inclination takes a lot of delta V, a lot of fuel.”

Greg Richardson, executive director of the Consortium for Space Mobility and In-Space Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing Capabilities, or COSMIC, a professional association that works to promote on-orbit capabilities, said the economics of on-orbit servicing just don’t add up in LEO.

So while 2007’s Orbital Express “was a great demonstration of technology—it showed what’s possible,” he said, “If we’re going to make on-orbit refueling routine, reliable, and safe, the primary place where that’s going to happen is where there are lots of clients: in the GEO orbit.”

In GEO, “refueling infrastructure can support many clients … and that’s the key to bringing down costs,” Richardson said.

Essentially, he sees solutions like MRV and MEPs as akin to the economics of a gas station compared to having to build out your own fueling infrastructure outside your home. “When you go and fill up, you don’t have to buy an entire gas station to fill up your car,” he explained. “You buy the gas that you need, and some fraction of that cost pays the overhead and fixed costs. … That’s what you want to do in orbit.”

The COSMIC community, which brings together representatives from government, industry, and academia, sees on-orbit refueling of satellites in GEO as the most commercially viable use case.

But the Pentagon is not limiting its research and development to that one regime. Its other three satellite mission-extending operations this year are:

- Astroscale U.S. Refueler. A commercial refueling satellite developed by the U.S. subsidiary of Tokyo-based Astroscale Holdings, this program is funded by the Space Force’s Space Systems Command. Scheduled to launch next summer, it will conduct the U.S.’s first hydrazine refueling operation in GEO, refueling a U.S. military satellite on orbit.

- Tetra-5. A Space Force partnership with the Air Force Research Laboratory, this program aims to demonstrate autonomous rendezvous, proximity operations and docking along with an on-orbit inspection and refueling operation.

- Kamino. Funded through the Defense Innovation Unit, this effort will put a satellite system on orbit carrying hydrazine fuel intended for transfer and delivery to refuel other satellites in GEO.