Experts Warn of Pacific Threats

By Matthew Cox

Ukraine’s drone strike on Russian bomber bases didn’t just shock Russia—it also raised alarm among U.S. officials concerned that American military installations could also be vulnerable to attack.

Nicknamed “Operation Spiderweb,” the daring June 1 operation prompted Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine to review U.S. base defenses and accelerate counter-drone technology for installations at home and abroad.

“Cheaper, attritable, commercially available drones with small explosives represent a new threat, as was exemplified in that operation,” Hegseth told Senate lawmakers June 11. “It’s a critical reality of the modern battlefield that we have a responsibility to address.”

Drones are only part of the problem: U.S. air bases in the Pacific are vulnerable to attack from long-range Chinese missiles, and cheap cruise missile technologies are proliferating around the globe.

Recent studies from AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, the Hudson Institute, and RAND, the federally funded research firm, have all recommended over the past year that the Air Force increase its passive and active defenses, from rapid runway repair and blast-resistant shelters to directed energy defenses against drones and new air defense systems to shoot down larger missiles.

The Army is responsible for base defense, and most missile interceptor systems, such as Patriot, belong to the Army. But force protection is in short supply compared to the potential threats. The Air Force has more control over what it spends to harden air bases than it does over when and where the Army deploys Patriot and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense, or THAAD, batteries.

Dispersing forces can decrease vulnerability to attack, but ACE locations won’t be invisible to China’s space-based targeting systems. China has placed hundreds of satellites in orbit to form a network designed to track U.S. and allied forces in the Pacific.

Former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall saw air base defense as a more glaring need for the Air Force than the future F-47 next-generation air dominance jet. “If we leave our bases vulnerable to attack, the F-22s, the F-35s, and the F-47s will never get off the ground,” Kendall said on the “Defense & Aerospace Report” podcast.

Tracking Foreign Stockpiles

China has poured resources into developing long-range cruise and ballistic missiles to hold at risk U.S. air bases in the Pacific. China has also demonstrated drone swarms and, according to RAND, aims to be the “preeminent producer and user of such systems.”

“China is capable of attacking all U.S. bases in the Indo-Pacific region,” researchers wrote. Yet “air base defense has not kept pace with the continued technological threats to air bases and other military installations.”

China’s stockpile of intermediate-range ballistic missiles, which can travel up to 3,500 miles, has increased from just 20 missiles in 2012 to 500 missiles in 2023—a 2,400 percent increase, according to RAND. Researchers also noted similar upticks in medium-range ballistic missile launchers and missiles, which can travel up to 2,100 miles. Those ranges also may have grown, RAND added.

U.S. bases are well within those ranges. Kunsan Air Base in South Korea sits less than 250 miles from China across the Yellow Sea; Kadena Air Base in Okinawa and Misawa Air Base in Japan are also within hundreds of miles. Andersen Air Force Base on Guam is now also in range of Chinese missiles, even though it is some 2,000 miles away.

Limits of Army Air Defenses

U.S. Army force-protection capabilities and capacity may not be aligned with the needs of air bases, said J. Michael Dahm, a retired Navy captain and China expert at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

“It appears that the Army has prioritized ground-based air defense for Army units, first and foremost,” said Dahm, who researches aerospace and China at the Mitchell Institute. Dahm authored a July 2024 report that concluded a lack of resources and funding caused air base protection in the Pacific to atrophy, even as threats grew in recent decades.

The Air Force’s primary defense is tactical redistribution, employing what it calls agile combat employment to “move aircraft around the theater to find places that they can operate from, probably for a short period of time, then pick up and move somewhere else,” Dahm said. “There could be greater investment in short-range air defenses,” Dahm added, suggesting the Army should invest in mobile systems that can be loaded onto a Humvee-sized vehicle.

But Daniel Karbler, a retired Army lieutenant general at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Missile Defense Project, disagreed that the Army had left the Air Force vulnerable. Karbler, who commanded the Army’s Space and Missile Defense Command in 2019 and the Pacific-focused 94th Army Air and Missile Defense Command from 2012 to 2014, said the Army has recently begun to funnel resources toward air defense to rebuild a huge gap in short-range defenses.

“Yes, we protect our Army forces, but not every infantry platoon or armored platoon, or even company, is going to have an air defense branch element,” Karbler said. “We have really pushed down counter-drone technology and capabilities, and we train these maneuver guys on using these systems, because we can’t do it all. … That’s part of what the Air Force needs to look at, too.”

Going it Alone?

RAND, however, recommends the Air Force “conduct a serious cost-benefit analysis of fielding its own active defense capabilities, ones that are tailored for air base defense in Pacific and European threat environments,” the report states. “‘Free’ defenses provided by the Army are understandably difficult to turn down but may simply be too limited in number and face too many compromises in capability to provide much real-world utility to a dispersed basing posture.”

Long-range systems are extremely expensive. A single Patriot missile costs $3.8 million, and THAAD missiles cost about $8.4 million each, Dahm wrote. The Air Force evaluated comparatively cheap air defenses and concluded that the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System could be a more cost-effective option. The NASAMS, which features repurposed AIM-9X and Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missiles, can deploy on C-130 cargo planes and consists of just three components: a radar, a fire control center, and a canister launcher.

Still, those are also pricey. Dahm said the Air Force probably should invest in technology with a lower cost per round, such as laser and microwave systems or even cannon-fired, maneuverable 30 mm to 155 mm projectiles.

“There is great promise in maneuvering projectiles,” he said. “The threat is coming from a particular direction, you fire the maneuvering projectile in that direction, and it can maneuver within certain parameters as the inbound cruise missile or threat maneuvers in front of it.”

An Army spokesperson told Air & Space Forces Magazine that the service’s integrated air and missile defense is “undergoing the most significant modernization in its history” by adding troops and fielding the Integrated Battle Command System. IBCS is designed to improve the way sensors and shooters are integrated across the battlefield to increase capacity and depth.

Over the next several years, the Army is planning significant fieldings of THAAD and IBCS-adapted Patriot batteries, the Mobile Short Range Air Defense System, counter-drone weapons and other air defense systems, the spokesperson said without elaborating.

Experts say the Air Force should also prioritize funding so-called passive defenses that make installations harder to destroy. The service has redirected hundreds of millions of dollars from passive defenses to higher-priority initiatives in recent years. It changed course to secure about $1.4 billion in fiscal 2024, researchers said.

While the uptick in funding is a good start, experts say it must continue. Air Force leaders should be taking advantage of the “significant momentum in Congress for increases and improvements to air base defense,” RAND recommended, adding that the service “should not be seen as dithering in air base defense investments, especially passive defenses.”

The RAND report was requested by Pacific Air Forces and the recommendations were presented to the Air Force last fall. The Air Force did not provide comment to Air & Space Forces Magazine by press time.

Hardened Shelters Needed

In 2004, Pacific Air Forces did begin to recognize the growing threat from China and advocated for hardened shelters at Andersen AFB, Guam, to protect stealthy B-2 bombers and F-22 fighters at a projected cost of $1.8 billion. But Air Force officials canceled the proposal due to a lack of funding, Dahm wrote in his policy paper.

Two decades later, China’s military has built hundreds of hardened aircraft shelters while the U.S. has built a handful, the Hudson Institute said in its own report earlier this year.

Hardened aircraft shelters cannot survive a direct missile strike, but they are capable of protecting against cluster munitions tucked into ballistic and cruise missiles, Dahm said.

“If I can build a really substantial, hardened concrete shelter with ventilation and plumbing and the whole nine yards for $4 million, that hardened aircraft shelter can sit there in the Pacific for decades,” he said. “But if I fire … two Patriots at every inbound ballistic missile, that is $8 million per engagement, and there is no guarantee that I am actually going to hit that.”

Keeping Runways Operational

Even if every aircraft survives an attack, cratered runways can still shut a base down, Dahm said.

The Air Force has been developing its Expeditionary Airfield Damage Repair program since 2021. Initial requirements called for the capability to deploy the equipment on four C-130s so a 16-member crew could resurface up to 18 craters in 24 to 36 hours, according to the Mitchell Institute paper, which added that the service should try to slash repair times.

That creates its own cost trade-offs, Dahm said.

Iranian Missile Hits US Air Base in Qatar

By Chris Gordon

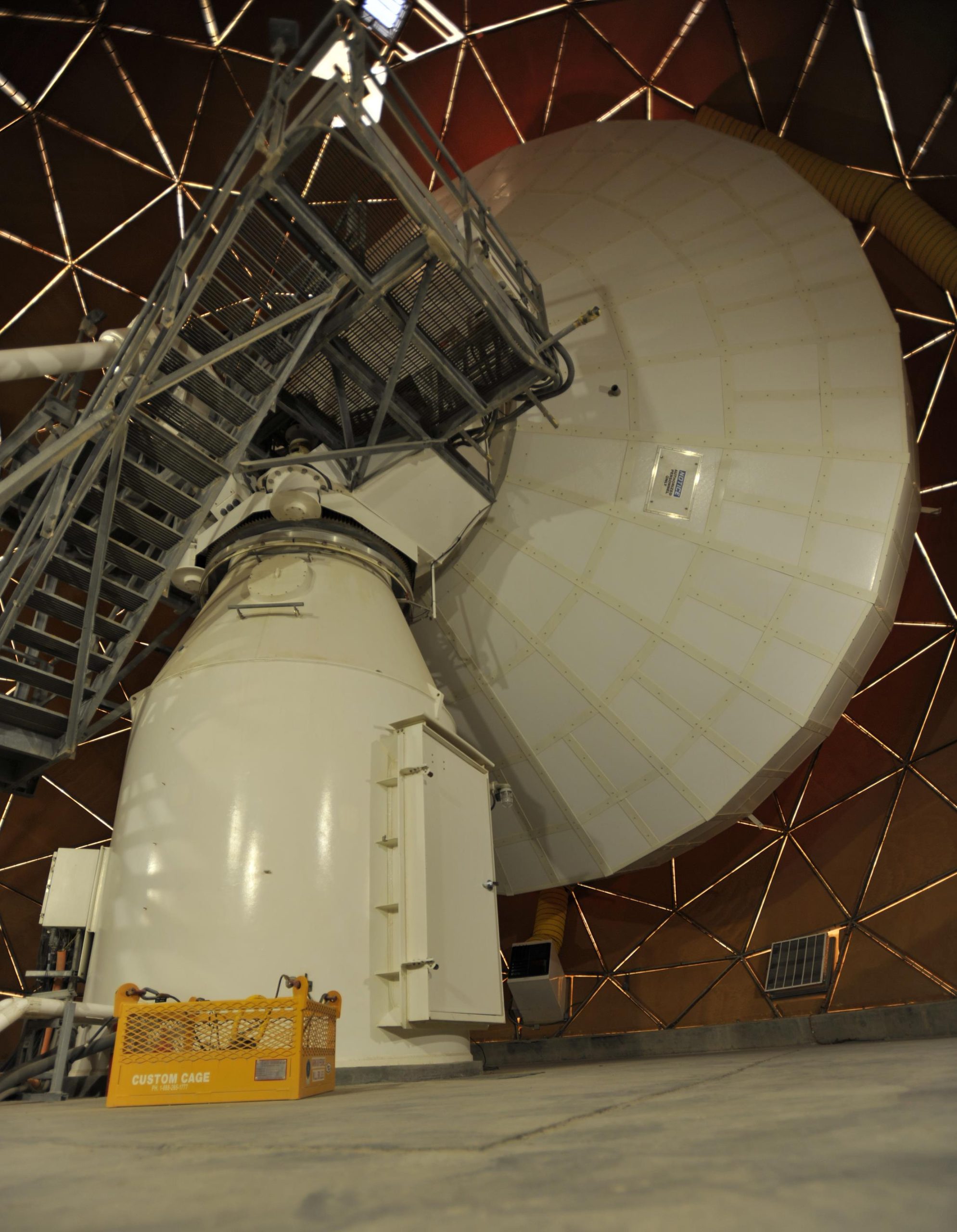

A ballistic missile fired at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar, part of a response to the U.S. bombing of Iranian missile sites days earlier, destroyed a radome on the base, the Pentagon told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

Al Udeid is the U.S. military’s largest base in the Middle East, and is also the closest to Iran, just across the Persian Gulf. Defense officials touted the success of U.S. and Qatari Patriot anti-missile systems in blunting the missile attack and initially did not acknowledge that one missile got through.

“One Iranian ballistic missile impacted Al Udeid Air Base June 23 while the remainder of the missiles were intercepted by U.S. and Qatari air defense systems,” Pentagon chief spokesman Sean Parnell said in a statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine. “The impact did minimal damage to equipment and structures on the base. There were no injuries. Al Udeid Air Base remains fully operational and capable of conducting its mission.”

Commercial satellite imagery reported on by Iranian media exposed the damage, which appears to have destroyed a radome that housed the modernization enterprise terminal (MET), a $15 million communications suite. MET “provides secure communication capabilities including voice, video and data services, linking service members in the U.S. Central Command area of responsibility with military leaders around the world,” the Air Force said in a 2016 release.

The base, which is normally defended by American and Qatari Patriot batteries, received additional U.S. Patriot systems that were relocated from Japan and Korea in advance of the attack.

In a briefing with reporters, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dan Caine said the base had been evacuated in advance of the attack. “There was a lot of metal flying around,” Caine said. “Between attacking missiles being hit by Patriots, boosters from attacking missiles being hit by Patriots, the Patriots themselves flying around and the debris from those Patriots hitting the ground, there was a lot of metal flying around, and yet our U.S. air defenders had only seconds to make complex decisions with strategic impact.”

Al Udeid typically houses approximately 10,000 military and civilian personnel. Iranian missiles, either fired directly from Iran or its proxy forces, have been a persistent concern for U.S. forces over the years.

The U.S. had taken steps to mitigate potential damage should Iran or its proxy forces attack U.S. forces in the region, moving most planes away from the base and evacuating it during the attack.

“Most folks had moved off the base to extend the security perimeter out away from what we assessed might be a target zone, except for a very few Army Soldiers at Al Udeid,” Caine said. “At that point, only two Patriot batteries remained on base, roughly 44 American Soldiers responsible for defending the entire base, to include CENTCOM’s forward headquarters in the Middle East, an entire air base, and all the U.S. forces there.”

Space Wing Honored for Missile Tracking

By Matthew Cox

The Guardians of the 11th Space Warning Squadron were honored as the top U.S. Space Force unit for 2024 for their role in thwarting Iranian missile barrages last year.

The Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies selected the 11th SWS for the first-ever General Atomics Space Force Unit of the Year largely for unit’s the precise early warning of incoming missiles, which helped Air Force fighter pilots thousands of miles away launch to destroy hundreds of incoming Iranian missiles aimed at Israel in April and October of 2024.

The new award follows the Mitchell Institute’s annual General Atomics Remotely Piloted Aircraft Squadron of the Year award and seeks to recognize the achievements of Space Force units that often operate in the shadows from bases in the U.S. to deliver critical capabilities to front-line warfighters.

When Iran began to launch missiles on April 13, alarms were set off at the 11th SWS and 2nd SWS operation centers. Just one missile will trigger an alarm that sounds “ding, ding, ding,” and before the attack was over, those alarms rang out 300 times.

Crews of a half dozen Guardians scurried to track each missile, verify the data, and pass it along as quickly as possible.

Capt. Abigail Flannery, weapons officer for the 11th, recalled how her teammates worked under extreme pressure in a recent episode of the Mitchell Institute’s “Aerospace Advantage” podcast.

“Those were both unprecedented attacks; we saw hundreds of missiles in a matter of minutes, and that really required us to look at how we’re doing our job,” Flannery said. “It really pushed our squadron to just figure out how [to] best tackle this new kind of threat … to make sure we’re providing that missile warning and missile defense that we need to be.”

Throughout 2024, the 11th SWS reported some 2,700 missile launches, evaluated game-changing battlefield technologies, and developed courses of action for responding to large-scale missile salvos. Their work that increased on-time warning by 69 percent, according to their awards package.

Based at Buckley Space Force Base, Colo., the 11th traces its roots to Operation Desert Storm, where it was first created to provide early warning of Iraqi Scud missile launches. Today, it operates the Space-Based Infrared Systems satellite constellation and the Overhead Persistent Infra-Red Battlespace Awareness Center.

During Iran’s April attack, the 11th was evaluating the next- generation ground architecture for space-based missile warning,known as the Future Operation Resilient Ground Evolution, or FORGE. That system will eventually replace the Space Awareness Global Exploitation, or SAGE, system, providing a scalable framework capable of handling greater volumes of missile launches more quickly, even while under cyberattack.

“We were actually in a trial period during the April attacks … and my team not only was trying to assess this new system, but put it to the test under literal fire,” the squadron’s commander Lt. Col. Amanda Manship said.