The U.S. cannot wait for a crisis moment to address China’s pacing threat.

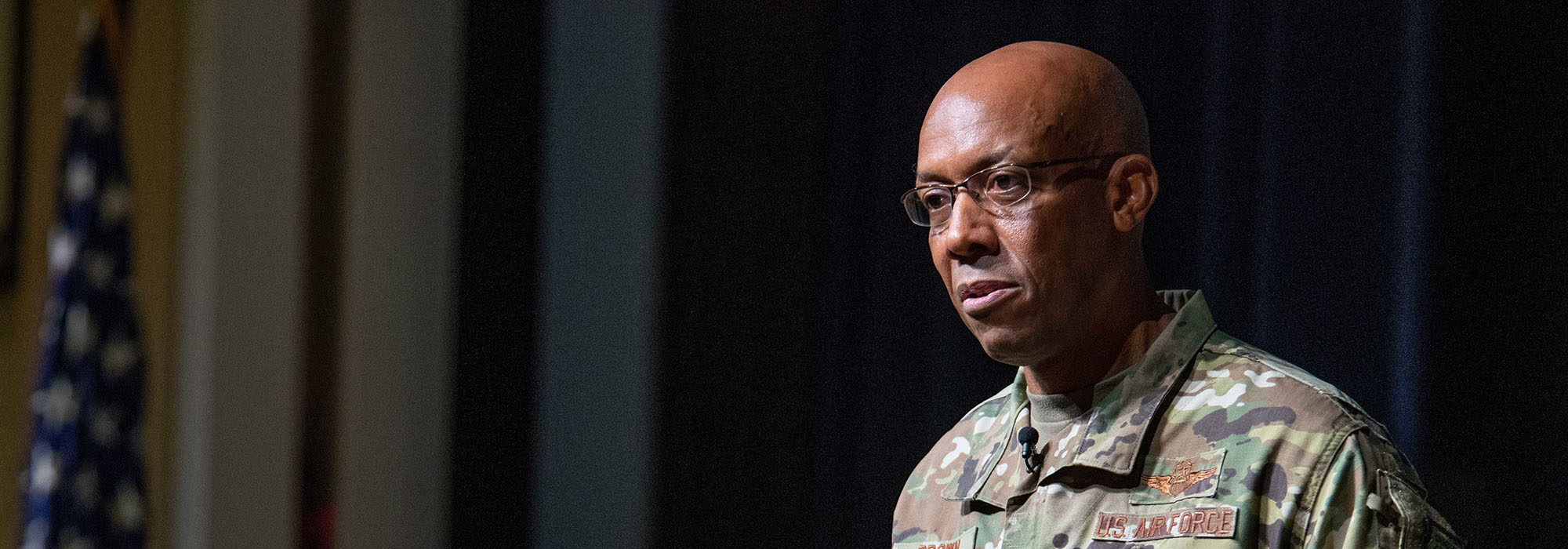

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. began his tenure as the service’s top officer with an order and a warning: Accelerate change—or lose (ACOL).

One year later, Brown sees a modicum of progress and a tightening timeline to achieve that imperative. Airmen and commanders must break from the status quo, as must lawmakers on Capitol Hill who have been unwilling to let the Air Force retire older aircraft.

“I think FY23 is the year. If we, as a department and as an Air Force, don’t make a big shift in ’23, then I’m concerned,” Brown said in an interview. “That’s the time we’ve got to make a shift.”

The Air Force faces mounting bills for a host of new aircraft: KC-46 tankers, F-35A, and F-15EX fighters, T-7A trainers, the B-21 bomber, the Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) aircraft, and an all-new nuclear ballistic missile, all at once. Brown needs bill payers and he and others are looking to jettison aircraft that are costly to maintain and that deliver less than optimum utility. Lawmakers, however, are hesitant.

It’s not just a hodgepodge. … You’ve got to step back from this and look at it a bit more strategically.USAF Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Brown Jr.

“You hear the discussion,” Brown says, eyes darting between his interviewers. “China’s a pacing threat … our adversaries are moving at a pace, and we’ve got to make sure we’re moving as well. That’s why I wrote ‘Accelerate Change or Lose.’ That’s why I’m doing all this engagement. Because if you don’t fully appreciate what the future is going to look like—or what the future threat [is], or where our adversaries are going—it’s hard to make that shift. You don’t want to wait until you have a crisis moment to go, ‘God, I wish we had done something.’ ”

ROADBLOCKS TO CHANGE

The Air Force has muddled its message over the years, laying out a priority and then changing its tune. Though there can be wisdom in changing one’s mind, the lack of a clear, consistent and coherent message raises doubts among those who can’t keep up with the changes.

Last summer, for example, the Air Force sought a modest cut to the A-10 fleet, then backtracked on some basing announcements after lawmakers moved to block the plan during the markup of the 2022 defense bill.

“The reason we announce things, and then pull it back, is all these things are interconnected,” Brown said. “Once you make one decision, it impacts the others. What we’re trying to lay out is: Actually, we do have a plan. … It’s not just a hodgepodge of looking at different bases and the like. You’ve got to step back from this and look at it a little bit more strategically, about how we look to the future.”

The A-10s are a good example. The Air Force wanted to cut one operational squadron at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz., and another in the Indiana Air National Guard. Indiana would get an F-16 unit, positioning Airmen there to shift to F-35s as they come on line. Davis-Monthan, meanwhile, would get A-10s and HH-60s from Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., and create “centers of excellence” for close air support and search and rescue, which in turn would open space at Nellis for newer aircraft. But if those A-10s stay, as expected, all those moves are on hold.

“Bringing on new systems … it’s not only the platform, but it’s the Airmen,” Brown said. “The Airmen that I have operating and maintaining this capability are the same Airmen that I have operating and maintaining these [other] capabilities in the future. I’ve got to make a transition. And so if they’re all tied up in this area, and we have things coming off the production line, I’ve still got to train those Airmen. It’s not a flip of a switch.”

Brown said he seizes every opportunity to engage with lawmakers, blowing up his schedule to be on hand for visits or meetings, and has “made due effort” to engage with Capitol Hill, and express that failing to give up some aircraft now will present “undue risk” later.

In these discussions, Brown said he lays out: 1. How the Air Force plans its future force; and 2. Here’s what the Air Force cannot do if it isn’t funded. “I don’t want to lay out a hollow force, right?”

“I’m not going to give up,” he said. “You hear rumors, but it’s not over until it’s over with the NDAA. I want to continue on with our plan. And will we have to adjust? I’m sure we will have to adjust. But I want to do it in collaboration with our key stakeholders.”

FUTURE FIGHTER FLEET

Brown made waves in May when he disclosed his “four plus-one” plan to narrow the fighter fleet from seven to five platforms, notably dropping the F-22 Raptor from the lineup. Too many aircraft, each with its own logistics tail, infrastructure, and personnel, is unsustainable for an Air Force desperately trying to modernize. Brown ticked off his long-term vision—F-35A, F-15EX, F-16 (or its eventual replacement), and the Next-Generation Air Dominance platform—plus a smaller fleet of re-winged and upgraded A-10s.

The F-22 will be replaced by NGAD in the 2030 time frame, he said. It may still have life left in it, but “it’s among our most expensive fleets to operate.” He committed to continue to modernize those jets for now, but added, “what we want to do is get to something that, across the board, is our sustainment to be able to operate at a reasonable rate.”

The secretive NGAD will then be able to directly fill the F-22’s air superiority role after the Raptor’s siren song, but not on a one-for-one basis. Just how many NGADs the Air Force wants is undetermined. “I don’t want to come out and say ‘Here’s what the number is,’” he said. “ Things might change. But I want to have a range of things that we can look at to go ‘OK, here’s roughly where we need to be.’”

The Air Force has a total of 186 Raptors; plans indicate thus far that NGAD might yield a rolling series of disparate aircraft, but no more than 100 or so each.

Additionally, Brown said the average age of the fighter fleet is 29 years and growing, with the F-22 becoming one of the older aircraft by 2030 as F-35s and F-15EXs come on line. New systems such as NGAD, developed with open architecture and agile software, can also be upgraded much faster using software updates as opposed to more hardware-driven upgrades for F-22 systems.

All these changes flow out of detailed analysis and wargaming in which the Air Force took tough losses against a high-end adversary. That’s what’s driving the need for rapid change.

“We’ve had strategy in the past of where we wanted to be, but I don’t know that it’s been to the level of depth and analysis and wargaming that we’ve been doing for the past couple years,” Brown said. “And so I feel pretty good about what we’ve laid out as a future Air Force design, that we’ve put some good thought into it.”

The budget discussion is driven by costs and impacts to individual bases in many cases, and Brown said he is worried these concerns aren’t taking into account—enough of—what the rest of the world is doing.

“You’ve got to do it through the lens of the threat. Realize we look at things from a budget, but you’ve also go to look at the threat. What’s the threat doing? And I don’t know that we do that as much as we probably should,” he said. “We could slow down, but you’ve got to take a look at what the adversary is doing. Are they speeding up? And is our slowing down, in some cases, is it going to compete, is it going to deter, and will it win?”

ACE?

One way the Air Force is accelerating its change is through the expanding adoption of Agile Combat Employment (ACE): The process of picking up aircraft quickly to operate from an austere location with a small footprint, a key capability if the Air Force needed to fight in an unpredictable way against a major power.

The process of ACE began with deputy commanders of Air Force major commands coming together, following the lead of Pacific Air Forces and U.S. Air Forces in Europe, who each started developing their concept of operations in 2017. Now, wings across all Majcoms are developing their ACE concepts along with an Air Force effort to create a “multi-capable Airmen” syllabus to train Airmen to be ready to do multiple jobs when needed.

This development is an embodiment of Brown’s ACOL order, but it is developing differently depending on each Majcom or wing.

“Part of ACE is being able to be agile, so what I want to do is provide the intent and the structure to do things, but each wing’s going to do things a little different,” Brown said.

It’s a change in mindset that needs to take hold in the ranks, because if the Air Force gets into a major conflict and there are casualties, “you can’t go well, ‘no, no one’s going to do this, and I’ve got a union card that says I’m not allowed to do things.’ Yeah, it’s a change in mindset. We’re all capable, if given the opportunity.”

Brown points to a December 2020 visit to Prince Sultan Air Base, Saudi Arabia, as an example. During a demonstration, the local F-16 unit put a Viper on the flight line, with Xs around it showing how many Airmen are needed to operate it. By having Airmen do multiple jobs, they told Brown they could still deploy and execute with two-thirds as many personnel.

“So what they had was empty Xs and two-thirds as many Airmen as they would normally take because we gave them an opportunity to kind of think and relook at how we do things,” he said.

CSAF Brown on Making USAF Look Like America

The Air Force is actively trying to make its rated career fields more diverse, by identifying and removing barriers that have blocked underrepresented communities from progressing in USAF cockpits, but also simply giving younger people more opportunities to see what the career could be like.

“People only aspire to be what they can see,” Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. said in an interview. “If they’ve never had the opportunity, then they’re not inclined to go, ‘I want to do that.’”

Brown is speaking from his own experience. He said he knew about the possibility of military pilot training, but never seriously considered it until a Reserve Officer Training Corps summer camp in Texas when he got a ride in a T-37.

“It changed everything I wanted to do,” Brown recalled. “I said OK, now I want to be a pilot.”

The Air Force in the past year has increased its outreach to give younger people, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, that sort of view at what a flying career in the service could be. Using resources like junior ROTC and summer camps as ways to provide “those opportunities to experience what it’s like to go fly. We’ve done it episodically, but we’re much more committed this past year to bringing young people in so they can see well before they get into college and have that opportunity.”

“Once they’ve had a chance to do this, I mean they fall in love with it,” Brown said.

For those who are in service, the Air Force is looking at identifying and removing barriers to make the service’s cockpits more diverse. Just 2 percent of USAF pilots are Black. About 6 percent are women.

Brown said recent reviews and studies into addressing these issues have brought to light barriers. For example, the Air Force’s process for assigning slots for rated officers would include a higher score for Airmen who had prior pilot time. This meant Airmen with the means to have flown privately before joining would be more likely to get a pilot slot.

“I knew that would actually make you better, but it would also increase your score. And so that is a socio-economic barrier,” Brown said. “I knew when I was coming through, I don’t know if I could have asked my parents for money to go get a private pilot’s license. I don’t know that we had the money to go do that, or I didn’t even think about that.”

Also, Air Education and Training Command is revising the old Air Force Officer Qualifying Test and the Test of Basic Aviation Skills because they have aspects that negatively impact minorities and women. For example, the height requirement for those interested in a flying career meant women did not qualify at the rate that men did. These changes don’t “decrease the quality … but it gives them more of a fair opportunity to compete.”

The Air Force in 2020 and early 2021 started two reviews aimed at determining disparities in career progression and military justice negatively impacting different racial groups. The first review, focused on disparities facing Black Airmen, wrapped in December with the second, focused on those facing other racial groups and genders, was scheduled to finish in August 2021.

The first review included 123,000 survey responses, along with 138 in-person sessions, and 27,000 pages of other written responses. The resulting 150-page report outlined widespread issues, with Black Airmen reporting distrust with their chain of command and military justice, and data showing Black Airmen are much more likely to face administrative and criminal punishment compared to white Airmen.

Brown said data in the reviews “validated the impressions of our Airmen … that there are some disparities.”

The reviews show the Air Force needs to improve how it looks at data sets “to have a better sense of how different groups are being represented, how their opportunities are brought forward, and how they’re treated from a discipline standpoint.”

The Air Force has also stood up “barrier analysis working groups” looking at issues facing women, African Americans, Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and the LGBTQ community. These groups “give really good feedback on approaches we can take to change things.” For example, recent changes to the dress and appearance regulations to allow different hairstyles came from these groups.

“One thing that I think our Airmen appreciate is that they have a voice,” Brown said. “They had a voice with these two reviews, but they [also] have a voice through these barrier analysis working groups.”