Brown’s A-B-C-Ds for Accelerating Change

The Air Force’s new Chief of Staff has an easy mnemonic of how he’ll move the service to “accelerate.” He calls it the “ABCDs” of change: a focus on Airmen, bureaucracy, competition, and design implementation. In pursuit of rapid change, though, he’s worried that a USAF “culture of consensus” is hampering top-level debate and decision-making.

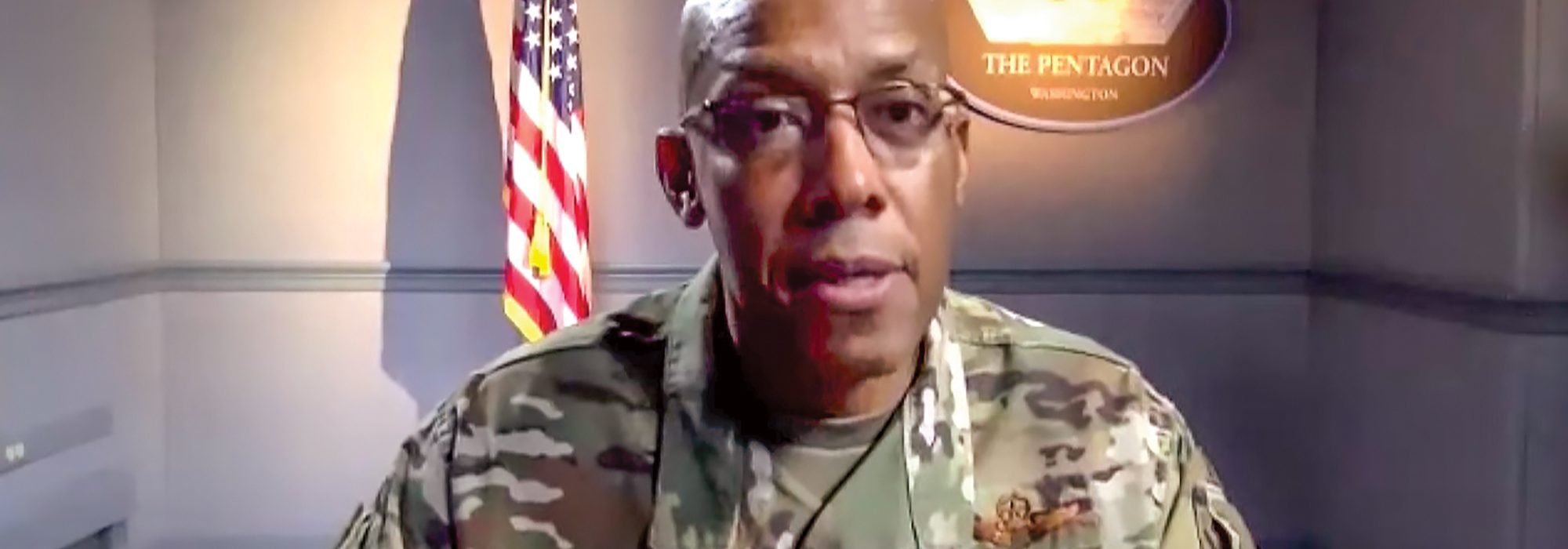

Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., in an October streaming event with AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies—his first extended public conversation about how he’s approaching his goals—said the ABCDs are the “what” to go with the “why” he outlined in his 14-page coming-in manifesto, “Accelerate Change or Lose.”

That document argued that USAF is facing “accelerants” in the form of rapidly advancing peer adversaries, the stand-up of Space Force, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racial disparities, to name just a few. The Air Force must speed up everything from command and control to how it buys hardware to keep up.

“This is about … taking a hard look at yourself,” Brown said. Part of that will be recognizing, “no matter what happens to our budget, we’re going to have to make tough decisions. We always have more requirements than money.”

The “A” is no surprise. Brown said the top priority must be taking care of Airmen and their families, and assuring their quality of life.

“They have to appreciate coming to work each day,” he said. Airmen need the right training and guidance, and should enjoy their jobs. “We have to take care of them in their off times,” and “retain the families,” who usually get the biggest vote on whether someone remains in the service, Brown observed. Airmen must also accept responsibility and take risks, and under his watch, “they can’t always wait and ask for permission” to do things that need to be done.

“We have to … let them know we trust them to do their job, at the same time they trust their leadership.” He’ll be focused on making sure Airmen can reach their full potential, are empowered to handle complex situations, and have “all the tools” they need.

“I hate bureaucracy,” he said; “I like cutting to the chase and getting things done.” While some bureaucracy is necessary, he’s convinced “we can do things a little bit faster. There’s a bit of redundancy [in the process], things we could do differently.”

Brown is looking to flatten the organization, especially in Washington. “We have so many government structures,” each requiring its own decision chain, that “we may be … canceling ourselves out,” he stated. “We tend to try to blame it on someone else,” he added, but USAF is going to “get on a timeline” for changing the bureaucracy and speeding things up.

The National Defense Strategy spells out how USAF must confront peer competition, Brown noted, and while he thinks the service understands Russia, given residual knowledge from the Cold War, with “China, we don’t have the same depth of understanding. What makes them tick?” He plans to make deeper study of China—and competitors generally—a bigger feature of professional military education, especially at the upper levels. But “C” for competition will also mean scrutinizing every Air Force action, particularly procurement, through “the lens of what the threat is. It may change how we acquire … future investments.”

The “D,” for Design implementation, focuses on shaping the future Air Force, and following through with the plan. The service is moving to develop a strategy “and then figure out how you fund it, versus the other way around.” It also stood up the Air Force Warfighting Integration Capability to manage the merging of USAF capabilities.

“That has been helpful,” he observed: to “lay out the future design and … focus” on it. Now it will be up to Brown to implement that design “so that when we get to 2030, and beyond, we have the Air Force we need.” But that will “drive us to some tough decisions.”

The “Air Force We Need” statement of requirements the Air Force provided at Congress’ request two years ago remains a good benchmark, but Brown said that budgets may dictate that he find ways to provide the called-for 386 combat squadrons of capability with a smaller footprint.

Corona Choices

During the Air Force Association’s virtual Air, Space & Cyber Conference in September, service leaders waved off questions about new directions in the fiscal 2022 budget, saying those choices would come at a major Corona meeting of top service leaders in October. But, Brown said the Corona produced few of those decisions.

“This is a process. I like to iterate things,” Brown explained, saying he’ll engage separately with the Major Command commanders and other stakeholders to “move the ball forward.”

The Majcoms need to be adaptable, he said.

As the former top Airman in Central Command and later in charge of Pacific Air Forces, Brown said he understands the pressure on field commanders “to make sure your capability is fully resourced.” But “we can’t do that for all the good ideas we have, so we have to figure out how to provide the best for the dollars we have available, and make those tough decisions.”

Under budget plans discussed at the Corona, not all Majcoms would get their No. 1 budget request, Brown said, but “we’ve got to look at the entire Air Force.” Some of their top priorities, “may not be the Air Force’s,” he added. He didn’t specify any of the systems or capabilities the service may have to give up to afford new investments.

How to minimize the bureaucracy on the Air Staff, and “how we engage” with Majcom chiefs, was another main discussion at the meeting.

Culture of Consensus

Brown expressed concern about the Air Force way of doing things “from the bottom-up,” saying its “culture of consensus” may be a brake on the system.

“It’s amazing, at this level, how many things come to you, and it’s already been decided” in the staff work already done. “I’m not even sure why I’m signing off on the piece of paper because they’ve already come up with the answer.” But he worries, “Is it the right answer?”

This culture slows things down because “you can’t get everybody to agree, so you don’t agree, and you keep working it until you beat down your dissenters,” and only then does an issue go to the boss for approval.

“Sometimes I want to hear what the other side has to say,” Brown asserted. He frequently criticizes the “meeting after the meeting,” in which those with views varying with the rest of the group hold their comments until the meeting is over.

“If you disagree, speak up,” he urged. “Don’t go out in the hallway and then disagree, because I’m not going to hear that part. … The train’s leaving the station, and if you have a different view, let’s have that conversation.”

On the other hand, he expressed impatience with those who offer dissent based only on judgment. “I get that, but there’s also got to be some data” backing up a contrary position,” he said.

Brown expressed frustration with decisions made before they reached the enterprise-level of debate. He wants to be “included in the conversation … earlier in the process.” If the Chief is not included until “the very end, I have very little wiggle room” to exercise enterprise-wide judgments.

By having more debate within the service, Brown said, “We can have a more consistent message of where the Air Force is headed,” for both the internal and external audience of stakeholders, “so we’re not fighting among ourselves, or competing among ourselves for dollars and capability all the way to the endgame.” This will “help us cut down the friction, maybe move a little bit faster.”

USAF must “figure out which [activities are] the most important, and where we take risk,” Brown said. He wants these conversations to happen “in front of me,” so he can see the impact of decisions on all parts of the force. Decisions for one part of the force, creating an “unfunded mandate” for another, creates problems, because then the “silos … fight among themselves because ‘the Chief said.’ I want to get them all in one room, as much as I can, to have these deeper discussions so we can make choices.”

Likewise, combatant commanders (COCOMs) will have to constrain their appetites for Air Force capabilities, so the service can invest in the future, Brown asserted.

He said he’ll have to “lay out risk” better with them, so they see the need for future capability as well as in the here-and-now.

“No one likes to lose anything,” he acknowledged, but COCOMs need to understand “here’s what the future looks like,” and “your successor is going to need” advanced capabilities. There needs to be “balanced risk,” he said. “I’m not asking the combatant commanders to take all the risk. I don’t think I should take zero risk. I think we both have to take a share of the risk.”

External Stakeholders

It’s a challenge convincing Capitol Hill and other stakeholders to think in terms of capabilities, which can be hard-to-visualize things such as networks, and not platforms, which have obvious constituencies, Brown said.

“We’ve got to get … our house in order to talk about capability, less about platforms, and really focus on mission areas,” he asserted.

Focusing on platforms is problematic, because each may have a suite of capabilities and requirements—sensors, weapons, manpower—that may not be obvious.

Changing a platform “may have some second or third-order impact on some new capabilities we’re trying to get done,” Brown said.

At an enterprise level, removing a capability here and there is “like a Jenga puzzle. You start pulling pieces out, that capability starts to go down. You may not see it for that particular platform,” but do it often enough, and a real deficit develops.

He pledged to engage “early and often” with Capitol Hill, the other services, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, industry, and others “so they have an idea of where we’re going.” He wants to know early if “I have a blind spot” or “if we’re talking past each other.”

He doesn’t want to “wait for the very end to find out we have a major issue with a key stakeholder … that we could have mitigated if we’d taken the time to engage with them early,” he noted.

Gaps and Seams

Brown said it will be essential for all the services to look at their combined capabilities under the Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC). If they don’t, they may not see “the gaps and seams, or the redundancies.” He has previously said he would push for more discussion of roles and missions, as the Army and Navy are pursuing long-range fires—an Air Force role—with hypersonic missiles.

The JWC will “give us an opportunity to look at how we are doing as a joint force, not just an Air Force,” Army, Navy, Marine Corps, or Space Force, Brown said.

Asked if there should be a roles and missions discussion on air defense—traditionally an Army role—Brown said, “We all have a responsibility for force protection,” and that it will be impractical to rely on Army Patriot and Theater High-Altitude Air Defense systems, because “there will not be enough [of those] to go around.”

“We need to have a conversation about who has responsibility for force protection … from the fence line to hypersonics,” inclusive of cruise missiles, ballistic missiles, and unmanned aerial systems.

The services also need to build into that thinking “the systems we’ll use in the future that are not the systems we have today,” Brown said. Those will include deceptive counter-C4ISR systems, “directed-energy, high-powered microwaves [and], high-velocity projectiles,” the latter of which, fired from a Paladin vehicle, shot down a cruise missile during the Advanced Battle Management System experiment in September.

Brown acknowledged his stated solution to most of the issues he raised in the event is to “have a lot of conversations,” but “that’s the way you get past some of the friction points … is to deepen your understanding. That’s the way I operate. … And that, to me, is going to help us accelerate.”