How Robotics and AI Will Transform Warfare and the Future of Human Conflict.

The first wave of the robotic revolution is underway: smart, precision-guided weapons are proliferating into every corner of war. The big cruise missiles and laser-guided smart bombs that revolutionized air campaigns in operation Desert Storm and thereafter were only a prelude. Today, precision is rapidly migrating to smaller, cheaper, and more plentiful classes of weapons and may soon be practically universal. The idea of “one shot, one kill” will become the standard for almost every class of weapon, large and small. By understanding the consequences of universal precision, we can see how this first wave of the robotic revolution will cause all the changes that follow.

Robotics and artificial intelligence are accelerating the rate of change and the lethality of military weapons. In “Beast in the Machine,” author George Dougherty traces both the history and future of autonomy on the battlefield. This excerpt is reprinted by permission of the author and his publisher, Ben Bella Books. Buy the book from your favorite bookseller.

When one missile, shell, or bullet produces the intended effect that previously required hundreds or thousands, weapon lethality increases by a hundred or even a thousand times. Such a huge increase not only offers tremendous advantages in combat, it alters the power relationship between weapons and targets and the fundamental dynamics of battle. The battlefield becomes a vastly more lethal place. The proliferation of precision robotic weapons will have major consequences for the shape of future forces, the tempo of battle, the role of information, and the need for combat AI. This first wave of robotic change, already rising, will drive and shape the subsequent waves, because the traditional military tactics and systems that worked in the past cannot survive on a battlefield ruled by universal precision.

A REVOLUTION IN LETHALITY

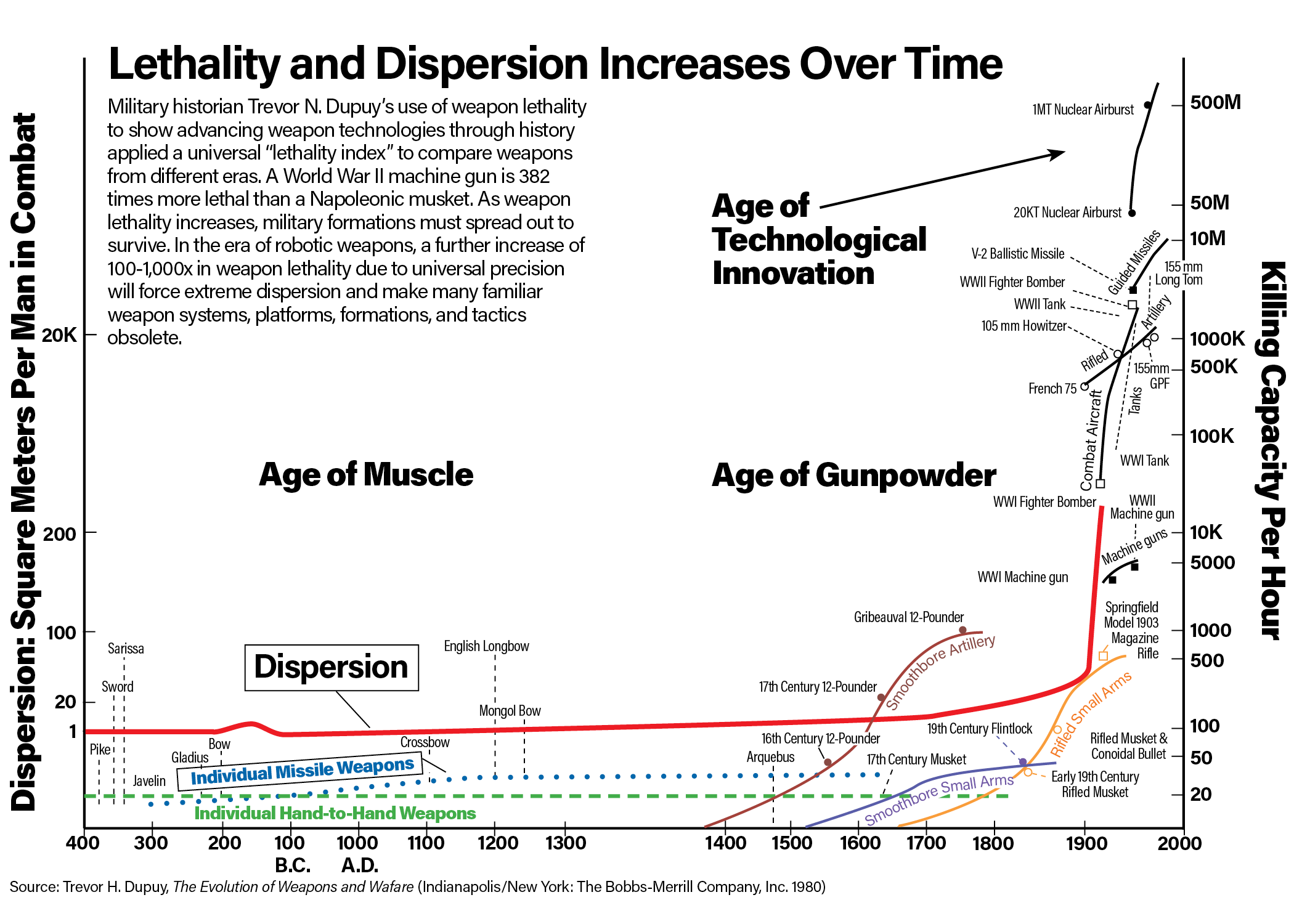

How significant will the consequences of this transition be? In 1964, military historian Trevor N. Dupuy introduced the concept of weapon lethality as a means for analyzing the effects of advancing weapon technologies through history. At the time, most military thinkers measured weapons by firepower, which was their output in terms such as rounds per minute, or by the throw weight of artillery shells per hour. Instead, Dupuy focused on their effects on the enemy. He defined weapon lethality as “the inherent capability of a given weapon to kill personnel or make materiel ineffective in a given period of time.” He proposed a universal “lethality index” that allowed weapons from different periods to be compared against each other. The smoothbore musket of the Napoleonic period received a lethality index score of 47. The late 1800s breech-loading rifle received a 229. The World War II-era machine gun received a lethality score of 17,980, due to its high rate of fire. The World War II 155 mm howitzer scored approximately half a million.

According to Dupuy’s index, a World War II-era machine gun was 382 times as lethal as a Napoleonic musket, and the World War II 155 mm howitzer about 125 times as lethal as a Napoleonic field gun. There is no doubt that a Napoleonic regiment would have been cut down in minutes on a World War II battlefield. Due to the tremendous increase in weapon lethality, the shape of military units and their tactics had to change dramatically between those periods. In particular, Dupuy noted that greater weapon lethality forced greater dispersion of military formations. He even proposed a mathematical relationship between weapon lethality and dispersion. World War II forces fought in much more dispersed formations, used low-visibility colors and camouflage, and emphasized mobility.

In the past, short ranges and low weapon lethality required the massing of forces. In the era of robotic weapons, long effective ranges and high lethality replace mass with “effective mass,” which is the massing of effects. The tightly packed formations of the Napoleonic period helped units to mass the firepower of their low-lethality muskets. However, those formations would be serious liabilities when facing the more lethal weapons of World War II.

Dupuy didn’t anticipate modern precision-guided weapons. He assumed that accuracy or precision was always about the same. As we have seen, a further increase in lethality of one hundred to one thousand times is reasonable in going from unguided munitions to “one shot, one kill” precision. That’s similar to the increase between the Napoleonic Wars and World War II. We can expect similarly dramatic changes to forces and tactics as a result. We can expect that a present-day force such as an armored battalion would be cut down in minutes on a future robotic battlefield. Many other features of today’s forces that made sense in the past may also become liabilities in the age of universal precision.

WEAPON-TARGET ASYMMETRY

Size itself may become a liability. The increasing lethality of smaller weapons due to precision is breaking the centuries-old symmetry between weapons and targets. Since the days when individual Soldiers faced each other with hand weapons, a weapon system could only be reliably defeated by a weapon system of at least similar size. For example, small warships fared poorly against bigger ones. The only gun capable of penetrating a battleship’s armor was the heavy battleship gun, which required another battleship to carry it. Similarly, it was a truism of armored warfare that the best anti-tank weapon was another tank. As bigger tanks emerged that carried thicker armor, their opponents needed bigger tanks to carry the heavier guns used to penetrate that armor. Engineers strove to build weapons that were ever bigger and more powerful. In the aggregate, this meant that opposing forces tended to be symmetric with each other. If a fleet had a dozen battleships, an enemy fleet seeking to defeat it needed a similar number of battleships, and so on. Military leaders and statesmen compared the numbers of battleships, tanks, aircraft, and Soldiers that they possessed to those of their allies and adversaries to assess the balance of power.

This symmetry held across different weapon types because of poor precision. For instance, an antiaircraft shell could theoretically bring down a large bomber. However, the shell had to be fired from a large antiaircraft gun, and due to poor precision thousands of shells had to be fired to shoot down the bomber. Defeating a bomber reliably required a combination of antiaircraft guns and shells that was similar in magnitude to the bomber. In fact, analysts in World War II calculated that the average cost for German antiaircraft gunners to bring down a heavy bomber was $106,976, which was comparable to the cost of a B-17 bomber at the time.

When Gen. Billy Mitchell demonstrated in 1921 that early bomber aircraft could sink a battleship, U.S. Senator William Borah asked, “If a $30,000 airplane can sink a $40,000,000 dollar battleship,” why build battleships? The effects of poor precision made that idea premature, but it started to become real in World War II when the first precision-guided weapons such as Germany’s Fritz X really did allow single bombers to cripple large warships under wartime conditions. Battleships largely disappeared after the war. Some observers are asking today: If a Javelin missile or an even cheaper armed drone can destroy a multimillion-dollar tank, why build tanks?

Today, a single F-35 fighter costs over $80 million and requires over 40,000 man-hours of labor to build. Yet a small robotic weapon that can destroy it or another advanced warplane, particularly when the plane is sitting on the ground, costs a tiny fraction. As part of a U.S. Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) project back in 2006, students used a radio-controlled plane to build a simple remote-controlled “aerial IED” capable of attacking parked aircraft. As they reported, “not including the cost of an explosive payload, the midshipmen were able to build this aircraft for a little under $300. Imagine a terrorist or insurgent group trading a $300 guided aerial IED for a $200 million C-17,” according to a thesis paper by Jeffrey A. Vish and published by NPS in 2006. Recent Ukrainian attacks have destroyed Russian bombers and transports using that very method. Advances in autonomy enable those kinds of attacks in large numbers. When those kinds of exchange ratios occur due to weapon-target asymmetry, the staggering economic costs are nearly as powerful as battlefield losses in forcing change.

Weapon-target asymmetry describes the increasing ability of small, inexpensive weapons to reliably destroy large, expensive targets. It is a key consequence of the advance of precision weapons, and it’s a powerful tool for predicting future changes to the character of warfare and military forces. With so much of the precision revolution still to come, this asymmetry will be an increasingly visible factor on the battlefield.

SURGICAL FIRE: 100 PERCENT HITS IS NOT THE LIMIT

When the circular error probable, or CEP, of a weapon decreases to less than the size of the target, the probability of achieving a hit on the target approaches 100 percent. However, achieving 100 percent hits is not the ultimate limit. The trend can continue much further.

As weapon precision continues to improve, it enables a weapon not only to hit the target but to hit a specific aimpoint within that target. In Operation Desert Storm, laser-guided bombs demonstrated that capability against large buildings. In one famous example, an F-117 pilot directed a laser-guided bomb into the central ventilation shaft of the Iraqi Air Defense headquarters, devastating the building with a single hit. Precision munitions have often been used to strike specific parts of large structures, such as the structural supports of Vietnamese bridges or the access tunnels of al-Qaeda cave complexes. Now, next-generation anti-ship missiles are providing the capability for an operator to choose specific aimpoints within a ship. That allows a relatively small missile to damage critical systems such as a ship’s engine or radar. Some very precise U.S. drone strikes have hit an individual terrorist sitting in a specific seat within a motor vehicle while sparing the other occupants of the vehicle. Ukrainian drone operators have showcased their ability to drop small anti-tank grenades precisely onto the weak points of Russian armored vehicles, even into open hatches. That enables a small, cheap grenade to destroy a multimillion-dollar tank.

The capability to hit points within a target with surgical precision increases the lethality of small munitions against large targets. Even small weapons can be devastating if they are precisely directed against critical vulnerable points. There are many examples of powerful targets being disabled by “lucky hits.” For example, in 1940, Britain’s largest battlecruiser, HMS Hood , was destroyed by a single shell from the German battleship Bismarck. It pierced her deck in just the right spot to travel into an ammunition magazine and ignite an instantaneous secondary explosion that blew the Hood to pieces. Imagine that, soon, such “lucky hits” will not be improbable accidents but the normal result of any attack. Large targets will become only as strong as their weakest point. In the hands of the fictional assassin “John Wick,” even a pencil could be a lethal weapon when used to precisely strike an opponent’s critical points.

Surgical-level precision increases weapon-target asymmetry. It gives a potent attack capability to small platforms that might have been unable to carry effective weapons in the past, like small observation drones. It also means that a given combat platform can carry many more weapons. For instance, an aircraft that in the past might have carried four 500-pound bombs for use against armored vehicles could potentially carry up to eighty 25-pound surgical fire munitions, enabling the aircraft to disable 20 times as many vehicles during a single mission.

Today, the early examples of surgical fire attacks require manual selection of aimpoints, for instance by using a laser designator or the careful video-guided positioning of a small drone. Soon, active terminal guidance powered by AI could automate that process. Image-processing algorithms could automatically identify the type of target under attack, look up the vulnerable points associated with it, and steer the weapon into one of those vulnerable points. Hence, robotic weapons could automatically use surgical fire to ensure that every hit is a lucky hit.

THE ACCELERATION OF COMBAT

Universal precision also implies a dramatic acceleration in the speed of combat. When it takes only one shot instead of many to destroy a target, combat happens much faster. When large precision weapons were first used at scale in Desert Storm, the efficiency of precision-guided bombing meant that air forces could attack and hit many targets at the same time resulting in shock and paralysis. As Gen. Ronald Fogleman, the Air Force Chief of Staff, put it in 1995, when the transition to precision-guided attack is complete, U.S. air forces “may be able to engage 1,500 targets in the first hour, if not the first minutes, of a conflict.” The result could be a conventional attack with the speed and shock of a nuclear strike, but with much greater discrimination.

Those concepts became codified as a new airpower doctrine of effects-based operations, based on parallel attack. As precision guidance migrates to smaller weapons, the same dynamic of speed, shock, and paralysis will apply to tactical engagements on the ground. An increase of 100 to 1,000 times in weapon lethality due to precision may result in a similar increase in speed. Because it will only take a short time to hit every visible target, high-intensity battles or firefights may only last a few minutes, perhaps even a few seconds in many situations.

The traditional spectacles of massed forces moving into battle, such as columns of tanks or fleets of ships, will likely disappear. Instead of representing power, such displays will represent dangerous vulnerability. Visible forces may become like targets paraded in a shooting gallery. During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian armored battalion tactical groups advanced in concentrated formations. Ukrainian drones monitored their approach, and they fell into ambushes by Ukrainian infantry with modest numbers of precision-guided anti-tank missiles. Stinging losses forced the armored battalions to withdraw. In the future, similar forces that so brazenly expose themselves to observation will be attacked simultaneously and wiped out in moments.

Without a dramatic change in the form of military forces, this accelerating effect may create a crushing advantage of attack over defense. Consider that in the past, the opening shots of any large campaign or small-unit firefight served to commence the hostilities, but they were unlikely to change the situation dramatically because most of the weapons that were fired would miss. In contrast, in the era of “one shot, one kill,” the opening salvos could tip a battle or the campaign decisively. An initial strike such as the Pearl Harbor attack, but using precision weapons, would be much more lethal and crippling. If the forces of one side can be targeted by the other, surprise attack becomes a dangerous temptation. In this manner, the calculi of conventional engagements may come to resemble, in miniature, those of Cold War nuclear confrontations. To reduce the temptation to strike first lest one’s own forces be wiped out, dispersion, camouflage, and other arts of concealment will be critical.

COMBAT AS A CONTEST TO FIND AND FIX THE ENEMY

On the future battlefield ruled by precision weapons, anything that can be seen can be hit and killed. Therefore, we can expect future forces to strive not to be seen, while making maximum effort to locate the enemy. Combat may change from a struggle to hit the enemy into a struggle to find and target the enemy.

A strike using a precision weapon includes a sequence of steps called a “kill chain.” Most of the steps are about collecting and processing the necessary information to target the enemy. The simplest version of the kill chain is “find, fix, and finish.” “Find” means detect the presence of the target, “fix”means tag it precisely with an aimpoint, and “finish” means destroy it with a weapon. More detailed versions, which specify additional steps such as “track” and “assess,” have since become popular. In all cases, the actual weapon strike is just a culminating step.

The contest to find and fix the enemy will become more explicit and intense. The U.S. Air Force and other military services have built a colossal multilayered intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) information enterprise to provide the information to feed today’s kill chains. It encompasses sensors ranging from small tactical drones, to powerful airborne systems like the airliner-based Rivet Joint and E-7, to constellations of surveillance satellites. The U.S. even established a new military service, the Space Force, to operate the growing network of space systems to collect and move data.

All those are backed by armies of intelligence specialists analyzing ISR data and making it useful for battlefield commanders. Data networks bring all this data together to create a real-time picture of the battlespace and coordinate actions by friendly forces, a process sometimes called network-centric warfare. When there are many networked sensors and weapons, they form a kill web that lets a kill chain be completed using any combination of those networked forces.

Targeting decisions lie at the center of network-centric warfare. If warfare was about wholesale destruction, only nuclear weapons would be valued because they accomplish that far more effectively. To the contrary, in real war, choosing targets carefully is vital, and decisions involve a lot more than just pulling a trigger. The military understands targeting as a comprehensive process. Current U.S. joint doctrine describes targeting as “the process of selecting and prioritizing targets and matching the appropriate response to them, taking account of command objectives, operational requirements and capabilities.” This is a systematic and multidisciplinary process and a command responsibility that requires a commander’s oversight and involvement. The process involves different areas of expertise and internal checks, starting with intelligence gathering and including the designation of the aimpoint for the munition. It then includes the assessment of effects following the attack. The responsibilities of targeting place a tremendous burden on those overseeing the use of precision weapons.

AI TO ASSUME SOME TARGETING RESPONSIBILITIES

The flood of ISR data is rapidly outstripping the capacity of human analysts to absorb it. In 2019 the U.S. director of national intelligence stated that under current trends, American intelligence organizations will need more than 8 million imagery analysts, more than five times the number of individuals that hold top-secret clearances in the entire government. That’s before the rise of universal precision. That burden can’t be pushed onto warfighters. Modern warfighters are already saturated with demands. As history shows, successful robotic weapons use their “smarts” to take the burden off the warfighter.

The advance of AI is helping to address this barrier of complexity and burden. Analysts in intelligence centers can use AI to efficiently scan vast amounts of video to quickly find potential targets. Warfighters and decision-makers can use AI to help analyze complex and rapidly evolving pictures of the battlespace, to distinguish important changes from unimportant ones and make faster and better-informed decisions.

Unmanned systems can use AI to do some of their own analysis and lower-level decision-making without sending burdensome raw data. After all, this is what we expect of manned systems. For instance, the crews of patrol aircraft looking for enemy vessels don’t simply beam back video to headquarters for analysts to assess. They do their own assessment and send notice when they find something. Edge computing using AI will allow unmanned ISR systems to act in a similar way to build a real-time digital picture of the battlespace.

In addition, AI will enable the countless precision-guided weapons to find their targets without overburdening the human warfighters. While it might sound radical, early forms of AI have long provided capabilities that allow smart weapons to perform some targeting tasks. “Fire and forget” missiles are already common in air and naval combat. Such homing weapons must be able to distinguish their targets from background clutter or other noise. They also must reject interference from countermeasures like infrared flares or radar-reflecting chaff that is intended to confuse or spoof them. New weapons use high-definition imaging sensors and image processing software to assess which objects in view are real and which are flares, decoys, or the results of electronic interference or background noise, and they then decide which object to pursue. They examine scenes in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum, called “multispectral imaging,” and look for distinctive shape or movement.

It is only a short step from selecting the real target among fake ones to selecting the target from among other objects.

Col. George Dougherty has served as a senior leader in defense laboratories, military headquarters, and the Office of the Secretary of Defense. He co-authored the Department of the Air Force’s Science and Technology Strategy. He has served in the Active and Reserve forces and, as a civilian, is a business strategist who helps companies navigate disruptive change. Any opinions expressed here are his own.