Receiving disability compensation has become a complicated process.

Capt. Cody Kirlin was deployed to Guam in 2019 when he woke one morning with severe neck pain. Examinations revealed the Louisiana Air National Guard F-15 pilot had two herniated discs in his spine, a relatively common injury among fighter aviators, given their high-G maneuvers.

What began as a painful injury has driven a debilitating wedge between the Air Guardsman and the military he had faithfully served since joining the Air Force in 2014. Twice the National Guard Bureau has determined Kirlin’s injuries were sustained in the line of duty, yet even now, six years later, Kirlin has received no Defense Department disability compensation, and he and his civilian employer have had to pay thousands of dollars to cover his two spinal surgeries.

Kirlin is among hundreds of Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve members who apply for and are denied disability benefits each year, the military having determined that their injuries were not sustained in the line of duty and therefore not worthy of military compensation.

Inconsistent language and interpretations are an ongoing problem, … which has led to errors in LOD procedural accuracy.

Air Force and Defense Department regulations say a Reserve Component member hurt while on Active-duty for more than 30 days is presumed in the line of duty until “clear and unmistakable evidence” shows otherwise, but rarely do officials provide such evidence.

In Kirlin’s case, the National Guard Bureau has, since 2022, insisted without evidence that Kirlin’s injuries were not sustained in the line of duty, even though it has twice before determined those injuries were sustained in the line of duty.

“It just makes my blood boil,” Kirlin said. “All this takes is one person to be a good human and do the right thing. But instead they choose to battle on every single point, and with the goal of retaining me without benefits.”

An Air Force Inspector General report released in February portrayed a military disability health system where inadequate training, poor communication, and zero oversight leave Airmen confused, distrustful, and with few avenues for recourse when their service branch disputes their claims that their injuries were sustained in the line of duty (LOD).

“[Air Reserve Component] wing, NGB, AFRC, and DAF are lacking LOD program oversight. There is no current adequate oversight of the LOD program at any level,” the report said.

Line of Duty

The problems stem from gaps in health insurance coverage. Active-duty members are covered by Tricare, the military health insurance program. But members of the Reserve Component (RC)—comprised of the Guard and Reserve—are not necessarily covered by the same system. Those that choose may acquire Tricare coverage in exchange for paying a monthly premium and copayment, but once on Active-duty orders for more than 30 days, they are automatically covered by Tricare at no cost.

For RC members hurt in the line of duty to receive long-term medical care and disability compensation, they must receive an in line of duty (ILOD) determination, which certifies that the medical condition was incurred or aggravated during military service.

An ILOD is the key to Defense Department and VA disability benefits, including medical retirement, which includes lifetime medical care under Tricare. A VA disability rating entitles recipients to lifelong disability payments, which unlike military retired pay are not generally taxable.

If a condition is determined to have been ILOD, then the member may remain on Active-duty until the condition is resolved or the member completes the disability evaluation system (DES) process, which determines whether the member can continue to serve and, if not, whether disability benefits are in order. Extending Active-duty orders requires the Air Force to issue Medical Continuation (MEDCON) orders.

If the Air Force rules the condition is not in the line of duty (NILOD), it is almost impossible to receive a disability rating from either the DOD or VA systems, according to the Government Accountability Office.

To start the LOD process, service members file medical records and paperwork with the local military medical provider, who offers an opinion to the immediate commander, who makes an interim LOD determination. The commander also makes an initial recommendation whether the condition is ILOD or NILOD before it goes on to an Air Reserve Component (ARC) LOD determination board, a panel of medical and legal specialists and personnelists who make the final determination.

The Air Force Reserve and the National Guard Bureau each have ARC LOD determination boards, and the final decision authority for each board rests with the top personnel official for AFRC and NGB, respectively. Spokespeople for both components said the ARC LOD boards’ decision aligns with local commanders’ recommendations about 84 percent of the time. It is the local commander’s responsibility to brief the service member on the LOD determination.

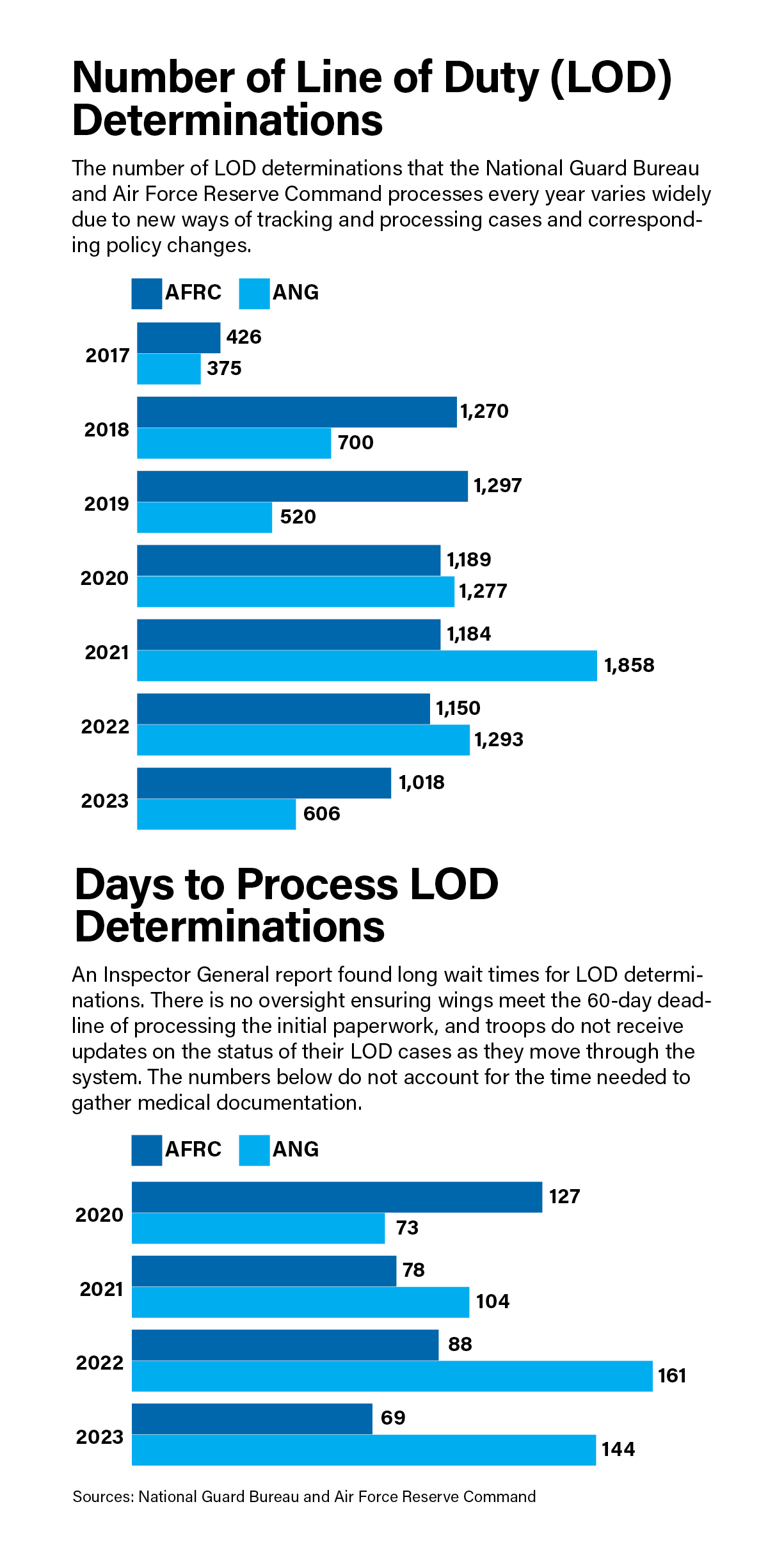

The number of LOD determinations that the National Guard Bureau and Air Force Reserve Command process every year varies wildly, according to data the two agencies sent to Air & Space Forces Magazine. Significant discrepancies were also identified in numbers provided pursuant to individual Freedom of Information Act requests.

An NGB spokesperson owed the wide range “to administrative changes—new ways of tracking and processing cases, and corresponding policy changes,” as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw a large number of activations.

From 2020 to 2023, about 80 percent of AFRC and ANG cases were found to be in the line of duty, with the most common cases being COVID-19 and acute musculoskeletal injuries such as sprains, strains, fractures, and lacerations. For NILOD cases, the most common included degenerative disc disease, osteoarthritis, hernias, and sleep apnea. Post-traumatic stress appeared among the top five conditions on both the ILOD and NILOD lists.

It takes a while to process a line of duty claim: the NGB ranged from 73 days in 2020 to 144 in 2023, while AFRC ranged from 127 days to 69 over the same period, though that does not count the time needed to gather medical documentation from members or providers.

There is no oversight ensuring wings meet the 60-day deadline of processing the initial paperwork, the Inspector General wrote. The Guard and Reserve components were “busting timelines left and right,” one Air Force personnel expert told the IG.

“Adjudications of LODs were going a year, two years almost,” the expert said. “And we needed a line of duty adjudicated much more quickly than 480 days, or 600 days, right? Because the line of duty is the key to everything.”

Missing the deadline by eight to 10 times the requirement became the norm due to: “Staffing resources, operational requirements, and insufficient documentation,” an AFRC spokesperson said.

Matthew Schwartzman, legislation and military policy director at the nonprofit Reserve Organization of America (formerly known as the Reserve Officers Association), said he’d spoken with about 20 members about their LOD. “Every single member that I spoke with encountered an issue with the line of duty determination process,” Schwartzman said.

‘Completely Baseless’

According to Air Force and Defense Department regulations, when a Reserve Component member is hurt while on active orders for more than 30 days, the condition must be considered ILOD unless the government shows through “clear and unmistakable evidence” that the condition existed prior to service and that it was not service aggravated. Clear and unmistakable means the evidence is undebatable.

But advocates and the IG report say the government almost never meets that standard.

“ARC service members are not provided sufficient feedback or evidence explaining why their medical conditions were found NILOD,” the report said. One senior enlisted LOD program manager (PM) told investigators that members are usually provided standard language out of medical literature that is very difficult to understand or explain.

In Kirlin’s case, the ARC LOD board had determined twice by August 2021 that the pilot’s injuries, cervicalgia and cervical radiculopathy, were ILOD; consistent with more than a dozen official Air Force records which also say that the injuries have not been resolved.

Kirlin was put on nonflying status and entered into the disability evaluation system. Kirlin retained his civilian job as an airline pilot, since flying airliners does not involve high G-forces, as flying fighters does.

But in December 2021, things went awry. An informal physical evaluation board (IPEB) compared an MRI taken in July 2021 with a made-up one from January 2021, one which the Air Force three years later admitted never existed.

The non-existent MRI found a new herniation in the July image indicating a new injury. That panel directed a review by the National Guard Bureau. One year later, in December 2022, the NGB determined that the original ILOD injury had been resolved and then aggravated by “an intervening event, i.e., bike ride and/or civilian flying activities.” The board concluded that the original injury had healed and the re-injury was not related to military service; they nixed Kirlin’s eligibility for medical retirement and benefits.

Col. (Dr.) Lisa Weeks, chief of NGB’s clinical case management, approved the NGB review, though she is an obstetrician/gynecologist and not a specialist in spine injuries.

Lt. Col. (Dr.) Wesley Vanderlan, the former senior medical examiner for the Louisiana Guard’s 159th Medical Group and a trauma surgeon who specializes in spinal surgery, also reviewed Kirlin’s record.

“I cannot emphasize enough that these conclusions from the IPEB are completely baseless,” Vanderlan wrote in a 22-page appeal of the NGB’s findings sent to the Air Force Personnel Council in 2023.

Able to perform only limited administrative duties since 2019, Kirlin is still required as a member of the Air National Guard to fly from his home in Colorado for monthly drill weekends in Louisiana, where he does computer-based training and other busy work before flying home. While the Guard covers lodging expenses, he receives no travel pay.

The NILOD determination means Kirlin does not receive Tricare Prime—which is health insurance without premiums or a co-pays—and loses possibly thousands of dollars a month in disability compensation.

Kirlin appealed the NILOD in November 2023 to the Secretary of the Air Force Personnel Council, submitting a 14-page legal memorandum with 33 exhibits in support, including Vanderlan’s 22-page statement. In January 2024, the council responded with a one-page memo. SAF/PC acknowledged “agency errors” in making a determination “based on a nonexistent [MRI].” But those errors did not prevent the review board “from making an informed decision.” SAF/PC acting Deputy Director Col. Selicia Mitchell concluded all of Kirlin’s spine injuries were incurred outside of military duty—overruling nearly every other official Air Force record.

Kirlin’s lawyers question those results: “It is entirely unclear how an abundance of objective, clear medical evidence, and highly favorable DOD guiding regulations, could have led to a one-page sweeping denial of the LOD appeal,” they wrote in a statement to the Air & Space Forces Association.

‘Canned Language’

Regulations let officials justify NILODs “through reference to medical literature,” and in most cases that is the only explanation members receive, said Brenda Gohr, an attorney who represents service members in LOD determination appeals. Gohr is a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve, but she spoke as a private attorney, not on behalf of the Air Force.

“They have moved from canned language that states ‘after consulting with authoritative medical literature’ to canned language that states ‘references include accepted medical principle, meta-analysis from UpToDate, along with guidelines from the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons,’” Gohr said. “That isn’t specific evidence that a service member can refute.”

Airmen and wing-level LOD program managers voiced the same critique in the Inspector General report. Members also cannot track the progress of their LOD, nor are they briefed on how the LOD process works.

“This lack of understanding is exacerbated by inadequate and, at times, non-existent methods of communication among service members, wing leadership, program managers, and the ARC LOD approval authorities,” the report found.

Master Sgt. Jim Buckley, a tactical air control party (TACP) Airman with the Mississippi Air National Guard, started suffering migraines following an airborne training injury. The ARC LOD board found the issue unrelated to his service. He has yet to be told why.

“At every level of appeal since then,” wrote Buckley’s lawyers, “… he has raised this issue, requesting the Air Force provide him the evidence purportedly relied on. Every time he has requested it, his requests have been rejected or ignored.”

Nor did the National Guard Bureau explain why it overturned an ILOD determination for Lt. Col. Christy Kjornes, a KC-135 tanker pilot in the Arizona Air National Guard. Kjornes requested not to publish the exact conditions to protect her privacy, and said she was initially hesitant to report her symptoms for fear of being grounded.

“Operators know on a professional level how to keep our mouth shut, so we can employ those skills when it comes to our personal health,” she said. “Once you suppress that long enough, then things really start to fall apart.”

While attending Air Command and Staff College at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., in 2020, Kjornes’ condition worsened. Her commanders and medical providers made an initial ILOD determination, which should have kept her on medical continuation (MEDCON) orders. But her Guard unit concluded otherwise.

When Kjornes returned to Arizona, her MEDCON orders were denied and the 161st Air Refueling Wing ordered an electronic version of the LOD determination form. It took nine months, and the resulting document left out one of her diagnosis codes and downgraded another to a less serious condition. The wing did not explain either action, and the NGB upheld the NILOD determination.

“There was zero evidence, just a generic reference to medical literature,” Kjornes said. “Nothing specific to me or my medical record.”

Now, however, suffering health issues and denied a line-of-duty determination, she was without pay and benefits and, lacking a civilian job, she had no income.

“I had no idea how long that was going to go on for, but the writing on the wall was that the appeal might not get approved,” she said. “So I thought I should probably offload my house and my mortgage before I completely depleted all of my savings.”

Lack of Training

In 2019, Buckley felt something give in his shoulder while carrying sandbags for a fitness test. “I thought I pulled a muscle,” the TACP said. But “from that point on, it just continued to get worse.”

Just like Kjornes, Buckley was taught to avoid reporting medical conditions. The reluctance to report medical issues is an added problem for members of the National Guard and Reserve, where “immediately reporting the health condition to command is the best way to obtain an affirmative LOD determination,” the Government Accountability Office wrote in a 2023 report.

“The more time that passes between the reserve component member developing a health condition and obtaining an LOD determination, the more difficult it becomes to demonstrate that the health condition developed during military service versus civilian life,” GAO wrote.

But the reserve components don’t often tell members this: All 15 stakeholders who the GAO interviewed said RC members do not always understand the importance of immediately reporting health conditions and documenting medical treatment. The Inspector General found the same problem, with all LOD program managers interviewed identifying an overall lack of understanding about the LOD and MEDCON programs.

Buckley tried to push through his shoulder issues, but within a year after the initial injury, he couldn’t even finish a pull-up. A personnel specialist told Buckley to report the time of the initial injury in a statement, but with more than 180 days having elapsed since the initial injury occurred, it was deemed a non-reported injury, and therefore not in the line of duty.

Buckley later learned the specialist had been wrong; the injury had to be reported within 180 days of the end of the orders covering the period when the injury occurred. Buckley had consecutive orders between the initial injury and reporting it, so he was still within the time limit. He also learned that a re-injury of an old injury is a new injury. So when he jumped on the pull-up bar and realized something was wrong, that should have reset the clock.

The IG found such mistakes common across the service. Two complainants told the IG they were improperly required to provide statements regarding their injuries that were then used against them; four others said their wings initially refused to submit LODs, despite an obligation to do so under Air Force regulations.

None of the PMs interviewed by the Inspector General received official training or instructions for their position, and there is no comprehensive, mandatory training program.

“Many reported feeling uncomfortable managing the program for many months to years before they could confidently fulfill their responsibilities,” the IG wrote. “LOD PMs report learning through on-the-job training, trial and error, and asking peers for advice.”

There is so little training that one of the IG’s recommendations was that ARC members “should be provided the rights advisement any time they are requested to provide a statement” about the origin or aggravation of their disease or injury. That is actually required under federal law, Gohr said.

“Why does it take an IG investigation to recommend ‘please comply with the law?’” she asked.

Workload

The Air Reserve Component Line-of-Duty Board for the National Guard consists of six medical providers, four judge advocates, and three staff from the Guard Bureau’s personnel directorate. Because of a backlog, the NGB recently added three additional lawyers to help. Reviewing LODs are just one of several primary duties for board members, NGB said.

On the Air Force Reserve side, the primary function of six medical providers is to provide medical case reviews as part of the LOD Board, with another three who can assist when needed. Up to five judge advocates provide legal reviews outside of their primary responsibilities, while two colonels from the personnel directorate review LOD cases as their primary duty.

Their workload is heavy: The Guard’s Board reviewed 10 to 36 LOD cases a week from 2018 to 2023, according to the Guard Bureau; while the Air Force Reserve reviewed another 20 to 25 cases a week over the same period. Files can contain hundreds of pages of medical records.

The Guard’s Board reviewed cases in 43 to 57 days between 2020 and 2023. For the Reserve’s Board, the average time to complete a review was slower, but improved from 266 days in 2018 to 69 days in 2023.

Inconsistent language and interpretations are an ongoing problem. Often, the determining factor is whether an injury was aggravated by time in service, but interpretations vary, which has led to errors in LOD procedural accuracy, AFRC told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

“Efforts have been made to clarify medical evidentiary standards, so they are applied consistently, particularly regarding service aggravation,” AFRC said. “Ultimately, human interpretation of complex legal and medical evidence is required to ensure LOD determinations comply with law and policy.”

The IG report agreed. “Chronic conditions that first exhibit themselves when the members are on orders are especially difficult to assess,” the IG said.

Specific medical expertise may be required, but that expertise cannot be guaranteed, as when an OB-GYN was assigned to review Kirlin’s spine injury.

The IG recommended the Surgeon General designate medical specialists to sit on and advise the LOD boards and appellate authorities. Whether that will happen remains to be seen, but no such directive has been made.

AFRC said physicians trained in aerospace medicine use their clinical judgment to recommend when to contact a specialist, and it is up to the LOD Board to decide when specialist consults are necessary. Similarly, the Guard has no formal criteria for when specialists should be consulted.

NILOD determinations do not identify the name or contact information for specialists if they are consulted.

‘A Really Broken Process’

Appealing a NILOD determination is an uphill battle. Guardsmen must appeal through the commander of the Air National Guard Readiness Center and Reserve members must go through the deputy commander of the Air Force Reserve. But because the LOD Review Boards provide little in the way of evidence, appellants have little ground to work with in contesting the results.

“How do I combat the research you did if you don’t tell me what you did?” asked one Airman in the IG report.

An LOD program manager agreed. “When I have a case that I believe … ‘this is in the line of duty, you know, and we need to appeal this.’ … I have to phone a friend in AFRC and say ‘hey, can you read me the internal comments so I can see why they’re feeling this way?’” the program manager said. “So that is, I think, a really broken process.”

Most appeals are denied with a single sentence: “Your appeal is denied under DAFI 36-2910,’” with no further justification or explanation, Gohr said.

The Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records is the final appeal authority. AFBCMR considered 42 appeals from fiscal 2019 to fiscal 2024, and just 14 (33 percent) were successful.

Appealing is a glacial process. Kjornes, the KC-135 pilot, first reported her injury in November 2020 and started her appeals in June 2022. Not until August 2023 did the BCMR finally rule in her favor. It took until late 2024 for her records and pay to be corrected. According to The Veteran’s Advocate, which represents RC members in these issues, a typical BCMR appeal takes 18 to 24 months to resolve.

Kirlin’s case took even longer to resolve. After the initial denial, the F-15 pilot submitted a 14-page NILOD appeal in November 2023, receiving two months later a one-page reply that acknowledged the erroneous reference to a nonexistent MRI, but held to the original judgment. On Dec. 31, 2024—more than five years after Kirlin’s injury—the director of the Air Force Review Boards Agency signed a decision to overturn the pilot’s 2022 NILOD. Now Kirlin is going through the disability evaluation system, waiting for a determination on whether he is fit for duty and to what extent he will be compensated.

“That’s only after five years, tens of thousands of dollars in legal expenses, inspector general complaints, and advocacy work,” said Jeremy Sorenson, a retired Air National Guard fighter pilot and advocate for reforming the LOD process.

Even with an ILOD, staying on medical continuation orders is not a guarantee. Federal law requires that members hurt on Active duty be put on Active orders to receive medical care while they go through the disability evaluation system—unless the injury is the result of gross negligence or misconduct. But Air Force regulations empower the ARC Case Management Division Chief to terminate those medical continuation orders, or MEDCON, if the member’s treatment plan requires less than two health appointments a week.

“Anything less than that … I begin to question really, why does that person need to be on MEDCON,” the ARC CMD Division Chief told the IG.

But serious conditions can exist and not require frequent medical appointments. “If you have a broken leg, you’re not going to go in to the doctor twice a week,” one complainant said. “‘How can ARC CMD expect you to have two appointments per week to stay on MEDCON orders?’ This doesn’t make sense.”

An LOD program manager agreed: “We’ve had many cases cut off because of that two appointments,” the PM said. “That’s not always efficient or it’s not good for the taxpayer. … If the member doesn’t actually need that two appointments.”

The Definition of Insanity

The IG report made 12 recommendations to improve the LOD process, such as requiring a “thorough and comprehensible explanation” of NILOD determinations; standardizing LOD program manager responsibilities and training; developing ARC-wide awareness training for troops and leadership; and conducting an independent review of the ARC LOD determination board process, to include the staffing and expertise of board members.

But Sorenson and Gohr say the problems are so deeply seated that only new leadership and more oversight can solve the matter.

“It’s great to say this should all be re-done, but without better direction or putting new people in charge of it. … The definition of insanity is doing the same thing and expecting a different outcome,” Gohr said.

The advocates know the 11 complainants who were interviewed for the IG report, each of whom had filed inspector general complaints of their own. Complainants said their health conditions were incorrectly determined to be NILOD and their LOD submissions had been processed incorrectly, but the vast majority of their complaints were unsubstantiated.

“You have a big report that says there are flaws in the system, and it’s not transparent, and the standards are not being applied appropriately, and there’s a large variation in what counts as clear and unmistakable evidence,” Gohr said. “If your overall review of the LOD process comes to conclusions like that, how then do you not have substantiated claims for those individual cases?

“There is a lot of fault within the system,” she added, “but nobody’s being held at fault.”

A Better Way

Issues with the LOD process arose as the Reserve Component transformed from a strategic reserve to an operational force over the past few decades. The Active-duty force is not big enough to counter instability in the Middle East, deter Russia and China, and respond to natural disasters at home all at once, the RAND Corp. noted in a 2022 report. This creates an “inherent tension and contradiction” in having a part-time force held in reserve that is also ready for conflict at any time.

Gohr understands that contradiction every time she goes for a run to meet physical training requirements. “If I step off a curb and break my ankle, that’s not in the line of duty, even though the only reason I am running is because I have to maintain physical fitness standards all year long, even when I’m not in [active] status,” she said.

Steps to Better Support Airmen

Jeremy Sorenson, a retired Air National Guard fighter pilot who has worked with dozens of service members affected by these issues, recommends 12 steps to improve the Reserve Component medical compensation process.

1. Comply with Title 10 USC and properly apply the legal presumption that injuries, illnesses and diseases are incurred and/or aggravated in the line of duty (ILOD) for members on military orders over 30 days.

2. Apply the proper, legal T10 USC evidentiary standards for all LODs.

3. Strict compliance with DODI 1241.01, 1332.18, and DAFI 36-2910 for all ARC members when they report injuries/illnesses/diseases.

4. Align DAFI 36-2910 and 36-3212 with DODI 1241.01 and 1332.18, and ensure strict compliance.

5. Provide MEDCON orders immediately upon report of injury/illness/disease as is required by regulation and law and remove ARC CMD’s arbitrary termination criteria.

6. Delegate final LOD determination to wing commanders, because they know the service member’s situation better than higher-level ARC LOD boards.

7. Remove the ARC LOD review boards’ authority to overturn wing commanders’ determinations.

8. Delegate appeal authority to an appropriate level, independent of the ARC LOD Boards.

9. Remove contractors from LOD processing, because contractors cannot be held accountable to the UCMJ and contracts create conflicts of interest.

10. Abolish the “review in lieu of/initial review in lieu of” process, a pre-disability evaluation system screening for which there is no ability to appeal.

11. Objectively investigate outside of DAF/NGB of all ARC NILODs and return without action “RWOA” LODs for the previous 5 years.

12. Instate a SAF-level Review Board to provide recourse for unlawful denial of LODs/MEDCON/IDES processing, comprised of independent, knowledgeable personnel.

Some advocate that the same no-cost, full-time Tricare coverage Active-duty troops get should be extended to Reservists and Guardsmen. That was a priority for Army Gen. Daniel R. Hokanson during his tenure as NGB chief from 2020 to 2024. Guardsmen and Reservists deemed nonmedically ready were more likely to be uninsured, according to a 2021 report by the Institute for Defense Analysis.

Roughly 60,000 Guardsmen do not have health insurance, according to 2023 data from the National Guard Bureau, and the nonprofit National Guard Association of the United States reported as many as 130,000 Reserve Component personnel have no “consistent” health insurance. There are about 760,000 RC members in total, so about one in five lack consistent medical care.

The IDA report estimated it would cost $2.5 billion to extend premium-free Tricare Reserve Select to all Reserve Component troops and dependents.

Hokanson told Air & Space Forces Magazine shortly before retiring in August 2024 that free health care for RC troops could benefit retention and make them more attractive to employers, who wouldn’t have to pay for their insurance. He said business leaders had told him “that is probably one of the best things that we could do to encourage businesses to hire Guardsmen.”

Bipartisan bills supporting zero-cost Tricare coverage for Guardsmen and Reservists have been introduced in recent years, but thus far have not passed.

Sorenson said health insurance would help, but won’t solve the problem. If an RC member is hurt, they might not be able to work their civilian or military job, leaving them without income. And before the member receives any compensation, the disability evaluation system must wait for an ILOD determination.

After five years, Kirlin finally won his case, but two out of three appellants weren’t so lucky. It takes time, money, and determination for members to get what they deserve, advocates say. For those lacking in any one of the three, they are left with injuries and thanks for their service—but not a penny more.