An F-35 drops a GBU-12 laser guided bomb over the Utah Test and Training Range in 2016. Laser guided munitions have increased accuracy, but more flexibility is needed. Photo: Jim Haseltine/USAF

America’s airpower arsenal is long overdue for a revolution in munition effects. Even as the US military’s combat aviation inventory continues to evolve into a robust fifth generation force with the steady employment of the F-35—and soon the new B-21—these aircraft are still delivering dated munitions with limited, fixed effects. Modernizing these munitions and the combat effects they produce is a growing, if under-appreciated, priority for the US Air Force and Department of Defense (DOD).

Modern airpower has never been more capable, yet the weapons they deploy have not kept pace. The basic aerial bomb body, a steel shell filled with explosive material, has hardly changed since its first use over a century ago.

Some 70 years after its initial deployment and use, the Mk 82 general-purpose bomb, a 500-pound, TNT-based explosive encased in steel, remains the air-to-ground workhorse munition of the Air Force and the other US military services.

To be sure, precision guidance technology has enabled a single B-2 to achieve the same effect as 1,000 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers in World War II. Yet in effect, the same “boom” from World War II-era bombs today is simply more precise. Aside from the addition of Global Positioning System kits and laser guidance capabilities to enhance the accuracy of those weapons, the actual munition effects—heat, blast, and fragmentation—are essentially unchanged.

Real-world requirements now demand a broader range of options for a given munition’s kinetic effect. Combat operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and beyond have repeatedly highlighted the need to limit collateral damage when attacking targets near friendly forces, innocent bystanders, or targets located in urban areas. At the same time, with near-peer military power competition on the rise, aircrews need the ability to bring extra kinetic power against aimpoints that may be hardened or buried underground. Moreover, the rise of real-time targeting in combat operations means aircrews today do not routinely know the kind of targets they will attack before bombs are loaded onto their aircraft. Without the ability to modify a munition’s explosive effect in flight, aircrews must often choose not to engage a target: Air component commanders tell us that as many as 70 percent of potential target opportunities go untouched for want of a suitable munition at a given time and place.

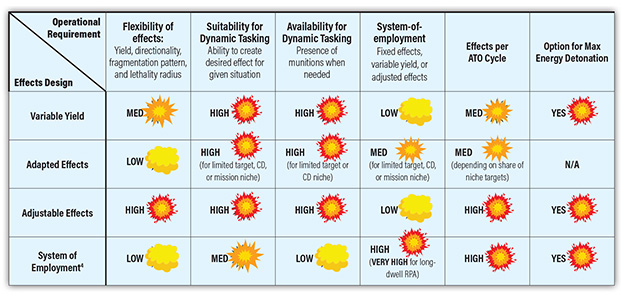

To address these challenges, we see four terms of reference for munition design:

- Variable yield effects—allows a real-time scaling of the power of the detonation, from a puff to the maximum possible yield.

- Adjustable effects—enables the shape and yield of the explosive envelope to be dynamically programmed for a broad range of targets and environments.

- Adapted effects—incorporates new concepts for addressing unique needs, such as targets in urban environments.

- System-of-employment effects—optimizes all aspects of the munition and its system of delivery. Examples of this methodology show that against certain target categories, a munition can yield the same kill effect as an Mk 82, but at a fraction of the size. Such design can add vastly more munition loadout to aircraft, such as the remotely piloted MQ-9 Reaper.

The Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) has translated warfighting priorities of the US combatant commands (COCOMs) into focus areas over the last several years. This effort yielded the carbon-fiber BLU-129 munition, an adapted-effects design for targets with high-collateral-damage potential or for supporting US troops in close proximity to adversary forces. The BLU-129 is a pathfinder for expanded development of munitions to meet greater warfighting needs through new design concepts.

Another key driver behind the need for enhanced munition effects options is that combat aircraft are increasingly high-demand, low-density assets. The Air Force is currently operating the smallest and oldest aircraft inventory in its history. Additionally, current mission capable rates on many aircraft are low, and pilots are in increasingly short supply. To best meet COCOM requirements amid these constraints, it is crucial that each sortie flown and every bomb dropped achieves maximum potential. The margins simply do not exist to repeat missions that could have been successfully executed the first time had there been a more flexible regime of munitions available. New munition effects could mitigate the results of a smaller US Air Force by increasing both munition flexibility and aircraft loadout.

To fully realize the potential of a munition-attained revolution, investment will be required in several key areas: advanced energetics, additive manufacturing (AM), and advanced developmental test and evaluation (DT&E) technology. Additive manufacturing is particularly important as an enabler of effects designs that were previously impossible to manufacture. It also promises to accelerate development and test cycles.

Col. Henry Rogers runs a pre-flight inspection on an F-16 carrying a BLU-129 before a sortie at Bagram Airfield in Afghanistan. The carbon-fiber munition was designed for targets with high-collateral-damage potential. Photo: TSgt. Robert Cloys

REALIZING NEXT GENERATION EFFECTS: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ACTION

Some efforts are already underway. Air Combat Command (ACC) and AFRL have rightly engaged with industry to ensure munitions research and development is aligned with warfighter requirements. Advancements will only occur if all stakeholders work together. Prioritization and coordination must also occur on the Air Staff; the Air Force Warfighting Integration Capability (AFWIC) and others must incorporate the potential of advanced munitions development into the broader vision of aerospace power.

- Policymakers should consider the following recommendations and focus areas to advance the near-term development of enhanced munition effects:

- Research and Development. First, incentives and resources must be prioritized to capitalize on developments in additive manufacturing. This technology must be stimulated through targeted investment, acquisition incentives, and adaptation of commercial innovations. The Air Force must craft a state-of-the-art template for weapons DT&E infrastructure, in order to support more rapid deployment of advanced munitions. While the service should protect and accelerate current resourcing for modernization at key facilities, such as Eglin AFB, Fla., more funding is needed. AFRL should set up a cross-functional infrastructure and capability design team that will be geared toward producing a next generation template for munitions DT&E activities.

- Culture. High performance munitions that afford flexible effects will not take hold culturally in military operational planning unless the Air Force first changes the way weaponeers and aircrews execute planning. This will require forethought, as these munitions enter service and eventually become routine tools in modern warfare. Training will undoubtedly be necessary, and Air Combat Command should begin experimenting with the value of flexible-effects munitions and prepare resources needed to adapt training and planning to exploit the value of these new designs to the fullest extent.

- Education. Top-level commanders and decision makers must learn the value potential new effects could offer, how they could be employed in combat, and how they could help close important capability gaps. Numbered Air Force commanders, who are tapped as combatant command air component leaders, should work with the Air Staff, AFRL, and COCOM officials, who otherwise may not understand the potential of these effects designs enough to factor them in when assembling priority lists to send to the Pentagon. COCOM staffs also should be informed about munition improvements that could answer the call for challenging operations against near-peer adversaries and offer greater effects flexibility in lower-end operations.

In addition to educating the COCOMs about the potential of new munition effects, it should be emphasized to these commanders that new effects designs could also mitigate the shortage driven by inventory and force reductions the Air Force and other services have faced since the passage of the 2011 Budget Control Act. Within the Air Force, especially ACC, the service is grappling with what is being dubbed an “effects crisis”—expected to last years—as not only the overall inventory has shrunk but buys of modern fifth generation aircraft are now under threat of being pared back. Fifth generation aircraft, such as the F-35 and F-22, have limited internal weapons carriage capacity, and any reduction in the force structure or planned buy of these aircraft exacerbates the effects crisis—fewer aircraft mean fewer weapons, and fewer actions that can be brought to bear on adversaries. The development of lighter, more compact, and more flexible weapons that can approximate or improve upon the effects of existing bombs (not just building smaller munitions) will assist in mitigating the shortage of overall munitions carriage capacity. While increased investment is important to meet COCOM needs for small munitions (in lieu of half-filled bombs as temporary solutions to collateral damage concerns, such as in Operation Inherent Resolve), this approach does not address the air combat effects shortage as it relates to more high-end scenarios, such as a conflict with a near-peer adversary such as Russia or China.

BALANCING PRESENT NEEDS, FOSTERING FUTURE CAPABILITIES

The demands of current operations in the Middle East and Afghanistan have understandably driven mandates to replenish existing munition stockpiles but, as a result, current Air Force resourcing for new munitions development is at a dangerously low level. Some key technologies that hold great promise for new and tailorable effects are now essentially on “life-support-level” funding. Yet, at the same time, potential adversaries continue to make significant gains in developing and testing their own new weapons. Funding must enable the Air Force to refill today’s weapons stockpile, while also investing in new munition-effects design concepts that can offset key capability gaps. Absent a deeper level of investment, these capability gaps could worsen over the coming decades.

The need for new munition effects has been publicly highlighted as a pressing issue since at least 2011, when AFRL noted that munitions development was lagging behind advances in fifth generation aircraft and next generation systems, creating significant challenges and limitations to Air Force-wide capabilities. This problem can only be effectively corrected by direction from the top of the Air Force, where future plans and programs are crafted—namely the acquisition policy and force development guidance being developed under the auspices of AFWIC. Senior AFWIC and Air Staff officials must ensure aircraft and munition effects are fused programmatically and do not wind up as separate and sequential development efforts. The service must defend this principle vigorously as the budget process evolves, and the resultant pressure from modernization begins to increase in the years ahead—whether as a result of program changes, budget cuts, force-structure adjustment, or technological challenges. Transparency in planning and analysis must be put forward when force structure is adjusted (up or down) to make sure Air Force leaders can express the resulting impacts across the range of military operations to decision makers in DOD and in Congress.

All of this becomes even more pressing as the Air Force and US military embrace new warfighting paradigms such as the “combat cloud”—where information will be gathered and rapidly processed and disseminated to relevant aircraft, assets, and actors. An integrated intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance strike-and-maneuver complex will link all weapons systems on land, at sea, in air, space, and cyberspace. Such an environment will compress kill chains and require rapid action with little preplanning.

By employing the combat cloud’s operational design with older weapons, all future operations would be fundamentally limited. US forces using older weapons will be limited in their ability to pair compatible weapons from scheduled loadouts with vastly increased strike opportunities, as a result of the combat cloud’s rapidly expedited kill chain. New munitions for this type of warfare must be more flexible, in terms of shaping effects for a wider range of targets and potential operating environments. Hence, advanced munition effects must be co-developed at the same time as these operational concepts; they cannot become an afterthought or secondary priority.

Advancing the evolution of munitions effects must also be accompanied by a rethinking of how to calculate the costs of weapons. AFWIC, ACC, and AFRL should examine the metric of “cost per effect” in order to guide future munition program choices and development efforts. A new regime of munition effects will generate benefit beyond just pairing a more effective weapon with a desired impact point. Greater systems efficiencies, the flexibility of the kill chain, aircraft weapons loadouts, and the potential logistical benefits of these new munitions are all relevant to a full-value budgetary assessment, no matter the resulting acquisition strategy.

New munition effect designs, and the operational flexibility they afford, will reduce costs in both dollars and strategic impact across DOD’s portfolios. It is essential that Air Force leaders and spokespeople promote the operational advantages of developing new munition designs to Congress and the general public.

SSgt. Patrick Waters (l) and TSgt. Sherman Padgett install a JDAM GBU-54 tailfin guidance kit on a 500-lb bomb in Southwest Asia. With the JDAM guidance kit, the weapon has a target error of less than 40 feet. Photo: MSgt. Caycee Watson/ ANG

PRESERVING AIRPOWER AS A DECISIVE FORCE

In order for this effort to succeed, both Air Force and DOD officials need to follow through on their oft-cited desire to better engage the aerospace industry to explain modern warfighting requirements and solicit ideas to address capability gaps.

Some efforts are underway to better match up ideas with requirements at organizations such as ACC and US Special Operations Command, but often these efforts only succeed to the extent that the right personnel support them—especially those with requisite operational expertise and a realistic understanding of how new technology can enhance current operational concepts and lead to new ones. Industry needs more direction on where to focus limited independent research and development funds. The Air Force should establish an ongoing working group to fine tune the rules and structures that govern the cross-flow of information between the government and the defense industry, and recommend modifications where needed to eliminate barriers to effective communication from federal acquisition regulations and Air Force instructions. Ultimately, building a safe and secure means to exchange ideas between the defense industry, academia, the US Air Force, and DOD will do more to foster a revolution in munition effects than will funding of any single initiative.

Over the past century, America’s Air Force has become indispensable for all successful military operations, and it continues a strong tradition of affording unique policy options to commanders and decision makers that cannot be replicated through force projection in other domains. However, continuous deployment since the start of Operation Desert Storm in 1991, coupled with the costs of combat operations since 2001, has led to an Air Force increasingly defined by the gaps between its available capabilities and real-world demands.

The US will not be able to restore its Air Force overnight. It is critical that a lack of resources do not starve a potential revolution in munitions effects, which will greatly aid these efforts. New munition capabilities will increase airpower efficiency and expand the flexibility that combat aircraft can offer. If prioritized, a powerful era of precision munitions is feasible in the near- to medium-term. Failure to capitalize on this potential will result in a mismatch between present-day munitions and increasingly capable aircraft. As the United States now faces rapidly modernizing peer-level military threats, the time to act is now.