Congress passed the Big Beautiful Bill. Now for the 2026 Budget.

By the time the 2026 defense budget request arrived on Capitol Hill in June, Congress was closing in on passage of the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act, a massive tax-and-spending bill that included some $150 billion for defense. The budget reconciliation measure narrowly passed the House on July 3 and was signed into law by President Donald Trump on the nation’s 249th birthday.

Now comes the hard part: The House and Senate are still hashing out their versions of the 2026 defense policy and spending bills. Those measures will spell out how much—and for what—the Department of the Air Force can spend in the next fiscal year, which begins Oct. 1.

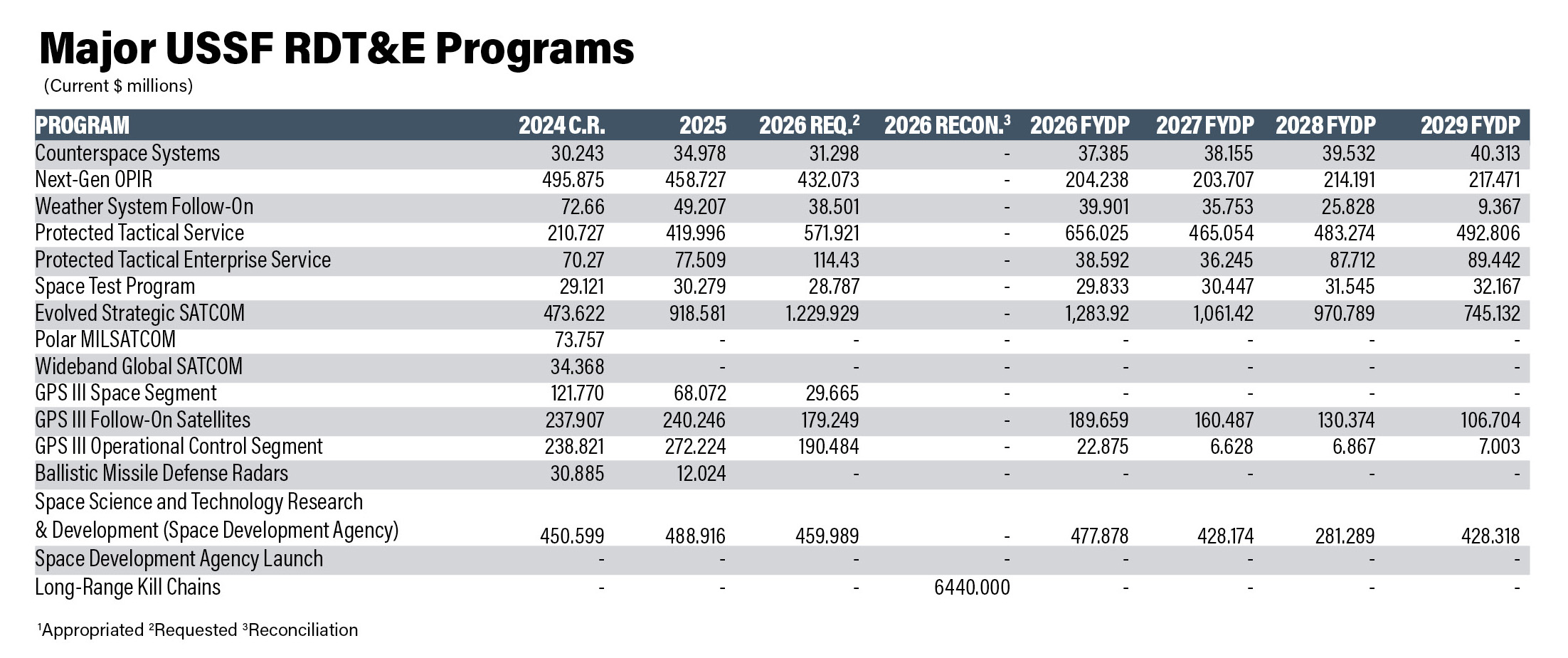

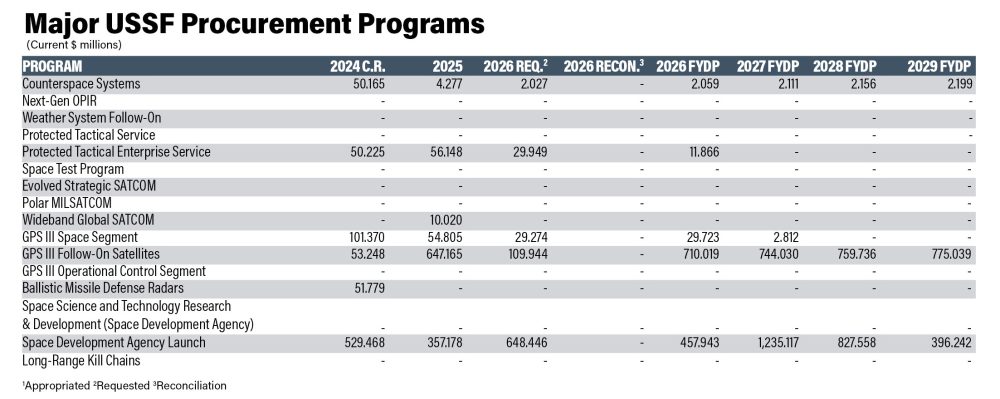

While the outcome of the annual legislation remains murky, this much is clear: The Air Force and Space Force go into the budget fight with Congress having lost ground compared to 2025. Observers say the Pentagon’s 2026 budget, if approved, would leave the Air Force smaller than today and with fewer new planes on order than a year ago. The Space Force, which will benefit from a piece of the $25 billion in spending for the Golden Dome missile defense initiative provided by the reconciliation bill, likewise sees no real growth in the base budget blueprint.

Whether funding is in the base budget or in a supplemental bill matters when it comes to building the next year’s financial picture, which is typically based on what was in the prior year’s budget alone.

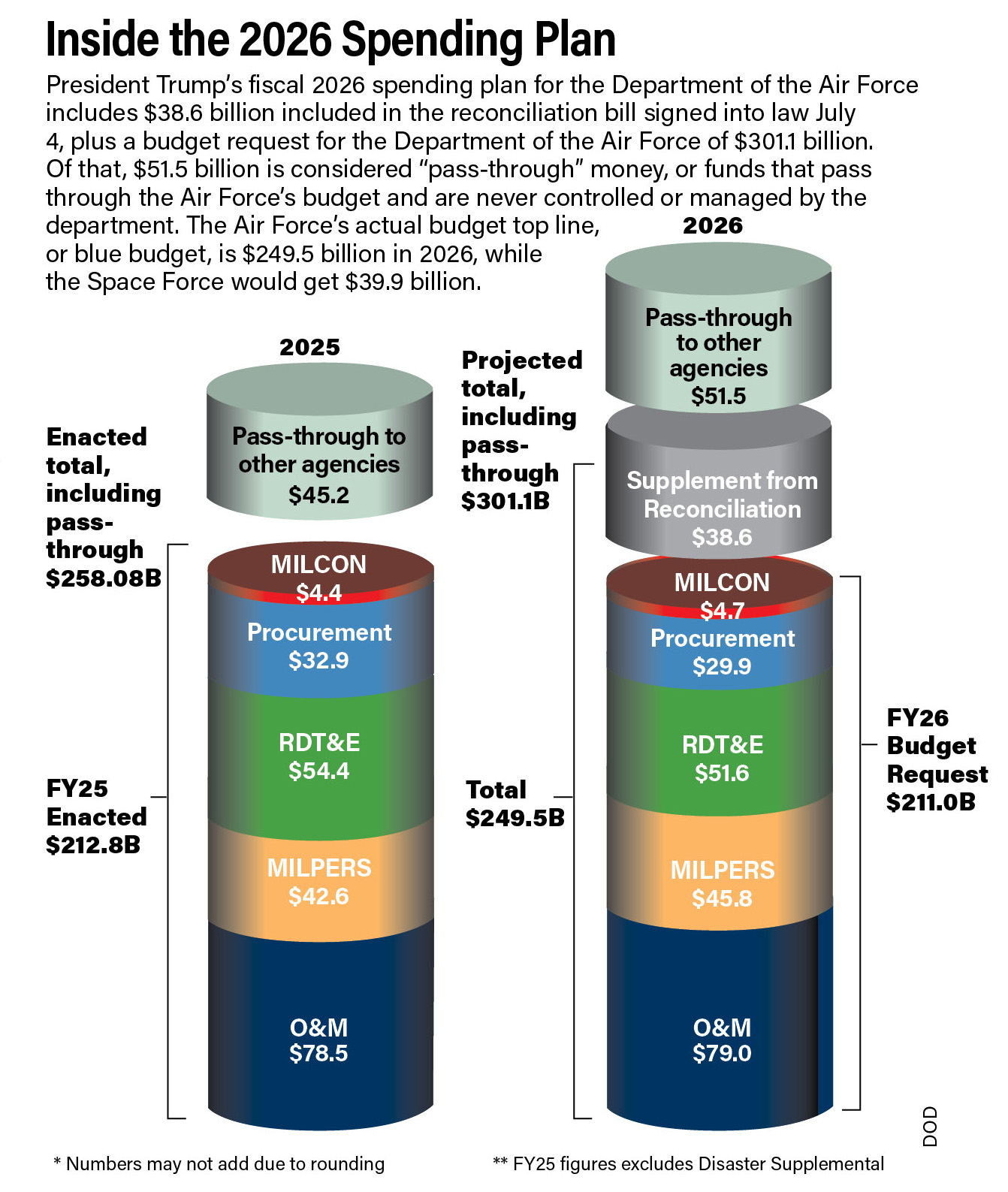

The President’s budget request seeks $249.5 billion for the Department of the Air Force in fiscal 2026. It funds a slight increase in military end strength, to 505,700, and a reduction of aircraft to a total of 4,600. Almost $210 billion would go to the Air Force and its 495,300 Airmen. The Space Force wants about $40 billion and 10,400 Guardians.

Another $51.5 billion known as “pass-through” funding is part of the Department of the Air Force request but funds outside organizations like the National Reconnaissance Office.

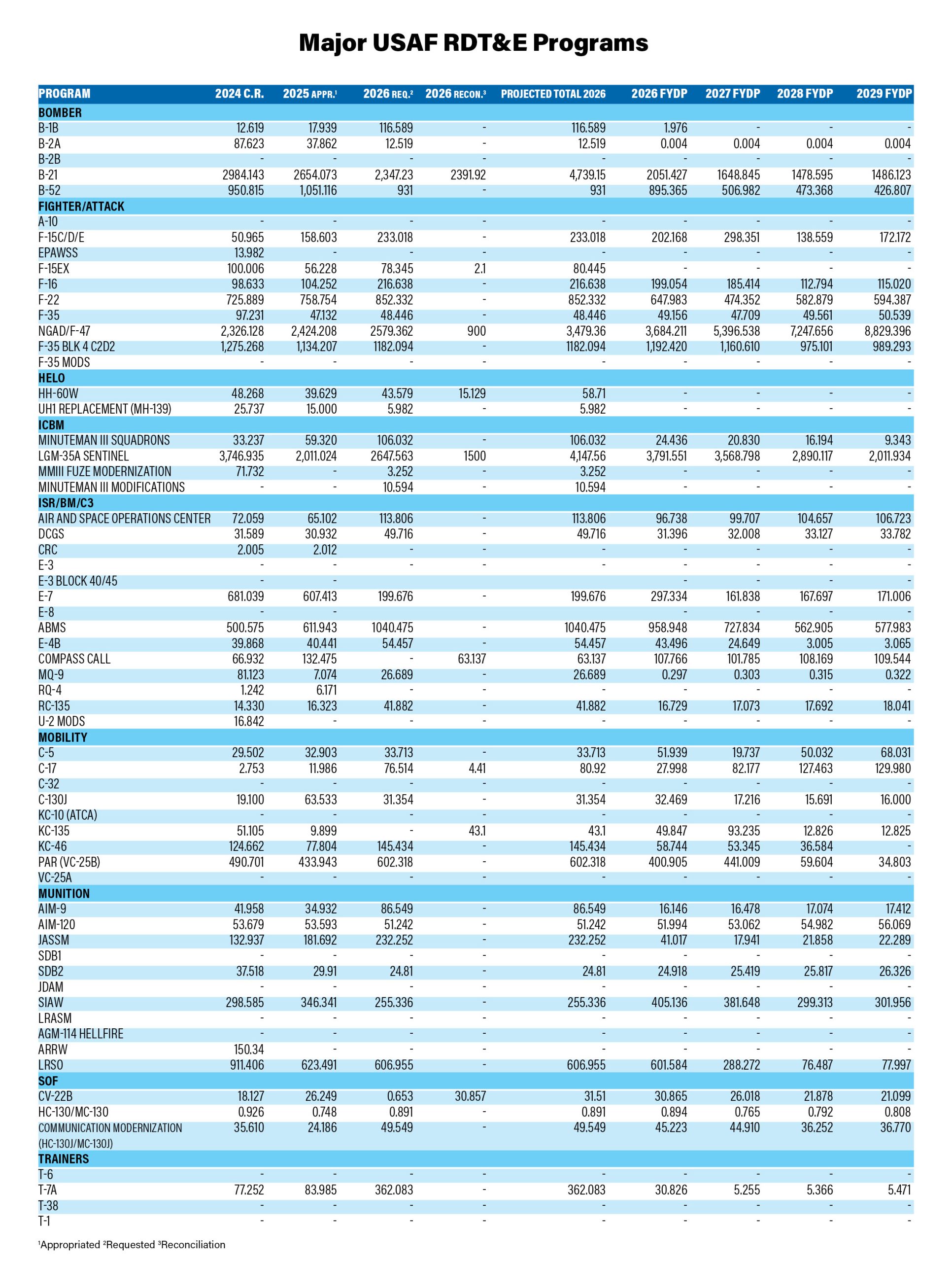

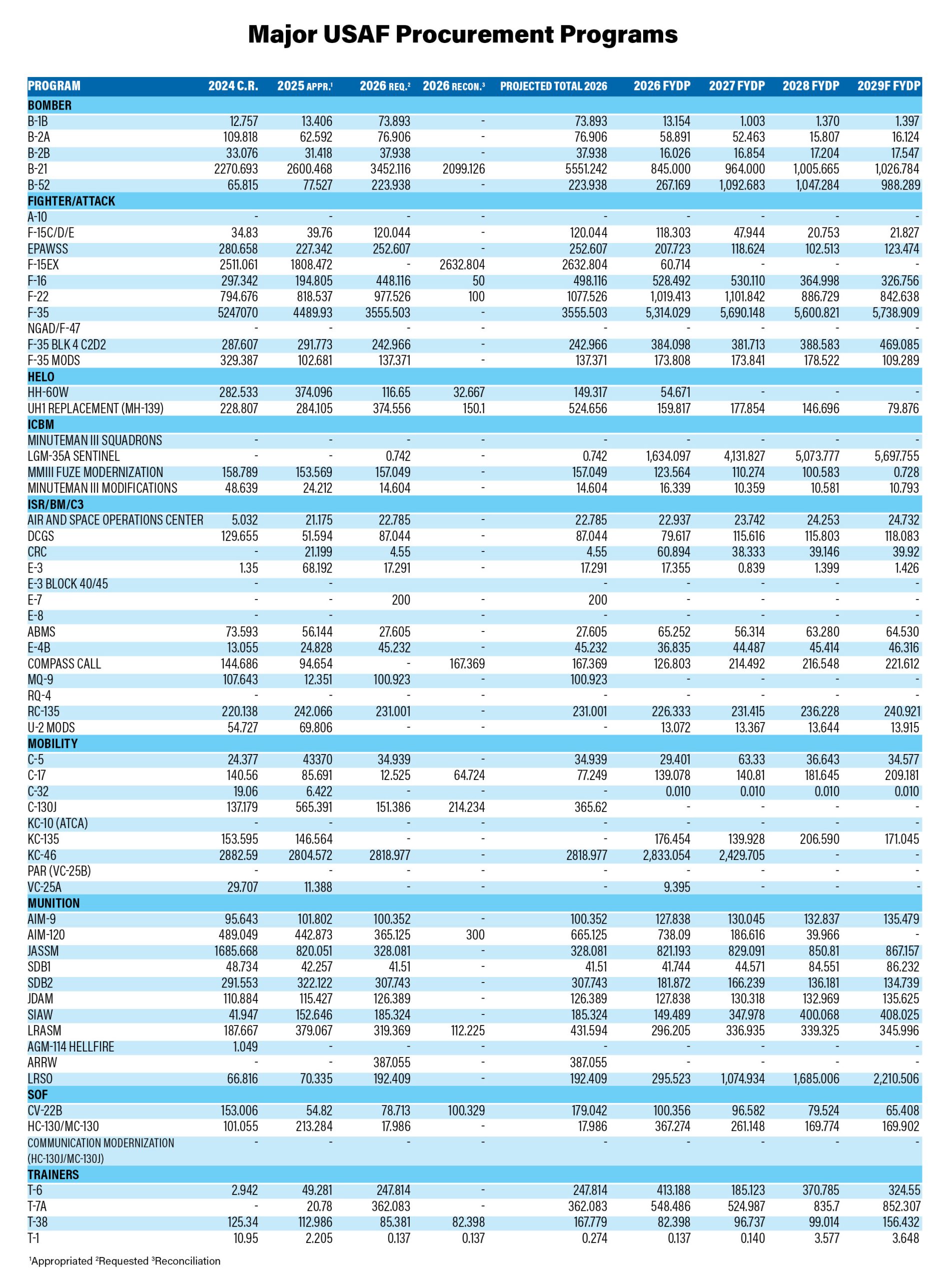

The budget plan accelerates production of the new B-21 Raider stealth bomber and funds development of the next-generation F-47 fighter and of the two Collaborative Combat Aircraft, the YFQ-42 and YFQ-44, which are competing to become the first high-end combat drones. Two hypersonic weapons programs, the Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon and Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile, would also move forward. So do new air- and ground-launched nuclear missiles.

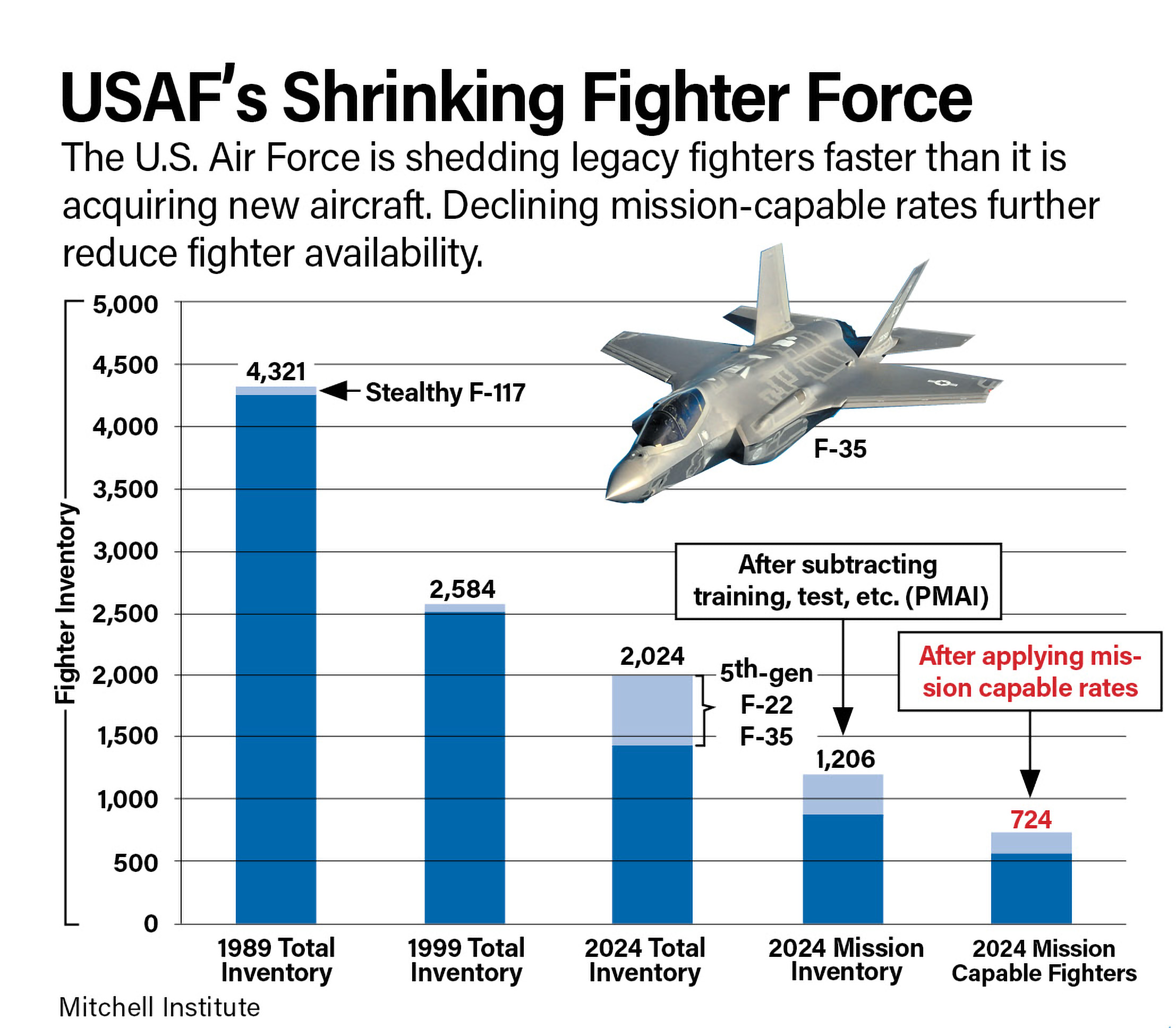

But other decisions raised alarm among Air Force advocates: The administration proposes slashing from 44 to 24 the number of new F-35A Lightning II jets the Air Force would buy and canceling outright the E-7 Wedgetail, a replacement for the aging E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System jets. The budget also slows pursuit of a stealthy aerial refueling plane and cuts flying time for Active-duty pilots to fewer than 1 million hours.

Other savings laid out in the spending plan include $1.7 billion from civilian staff cuts, $1 billion from canceled consulting contracts, $368 million in reduced travel expenses, $341 million for canceled climate initiatives, $39 million in savings from reduced security assistance to other countries, and $15 million in savings from canceled diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

Defense experts raised concerns that the Air Force and Space Force budgets lack a holistic view of what the U.S. needs to win future fights and diminishes airpower’s role in the joint force. J.J. Gertler, a longtime staffer at the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service who now works as an aerospace consultant, is most surprised by the decision to scale back certain future development programs, like the next-generation tanker and airlift initiatives.

“You’re seeing the next generation delayed, [and] also money coming out of procurement programs at the same time,” he said. “So you’re not building for the fight tonight and you’re not planning for the future fight.”

The Air Force is competing for funds with other programs that may be harder to nip and tuck. Building a ship is a more expensive, larger undertakings than producing airplanes, so it is harder to stretch out those programs, Gertler said.

“If you cut the annual procurement of an F-35, say, by 20 jets, you still get some F-35s and some useful combat power,” Gertler said. “If you cut a third out of a ship, it doesn’t float.”

Kari Bingen, who was deputy undersecretary of defense for intelligence and security during Trump’s first term, questioned the choice to cancel the Wedgetail and acquire a few Navy E-2D Hawkeye planes instead while waiting for a satellite-based moving air targeting system to materialize.

“I don’t see air and space as being an either/or,” she said. “I think you will need both, and each of them will have their strength to compensate for each other’s weaknesses. It starts to beg the question … where is the Air Force headed in its overall force design?”

Former top brass are pushing back on some of the proposed changes, too. Sixteen retired Air Force four-star generals, including six former Chiefs of Staff, have urged Congress to block the planned E-7 cancellation and to triple the number of F-35A fighters the Air Force will buy. In a media roundtable, they argued air superiority remains key to U.S. military strength and deterrence, and that investment is essential to correct a decades-long slump in air and space investment.

Gen. Kevin Chilton, a retired four-star who led U.S. Strategic Command and Air Force Space Command before becoming the spacepower chair at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, said it would be unwise to abandon the E-7 purchase even if a space-based solution were available today—which isn’t the case.

“We have to remember that the space domain today is arguably more vulnerable than any other domain,” Chilton said. Although “we have visions for ubiquitous, large numbers of satellites” doing reconnaissance and surveillance, that has yet to be proved in real-world operations, he said.

“Now we’re saying we’re going to throw [air moving target indication] into space. Well, maybe we will one day, but the challenges there are quite difficult,” Chilton said, noting that aircraft and enemy targets move in three axes and at different speeds.

The E-7 is “a priority” for House Armed Services Committee Chair Mike Rogers (R-Ala.) and Ranking Member Adam Smith (D-Wash.), a senior staffer said while briefing reporters on the committee’s budget bill. The draft added $600 million to the $200 million the Pentagon requested to wind down the E-7 program; the combined total of nearly $800 million is more than double the amount the Air Force projected last year it would need for the program in 2026.

An Atypical Year

Here’s how the annual budget process is supposed to work: Each branch of the military, led by their civilian secretaries, submits a spending plan for review by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the defense secretary and his deputies. The plan then goes to the White House Office of Management and Budget. Final decisions are made and the budget is submitted to Congress, with thousands of pages of justification outlining every program and plans for spending in future years. Budgets are supposed to get to Congress in February and be approved by the time the next fiscal year starts Oct. 1. It almost never happens that way.

This year’s piecemeal rollout started with broad-brush figures released May 2, followed by the bulk of the details on July 1. By then, all four congressional defense and appropriations panels had held hearings—without having seen the budgets they convened to review. The House defense appropriations subcommittee had already debated and advanced a defense spending bill on its own.

Nearly $39 billion—or 15.5 percent—of the money the Air Force and Space Force is on tap to receive in 2026 comes from the spending law enacted in early July. That includes more than one-third of the Space Force’s budget and 12 percent of the Air Force’s. The result could put both services in a precarious position in the future.

Though the defense portion of the reconciliation package was intended as a five-year investment in the Pentagon’s most pressing needs, the Defense Department plans to use 80 percent of that funding in 2026 to make up for an otherwise no-growth budget.

“This budget is a cut rather than a path to peace through strength,” said David Deptula, a retired lieutenant general who now runs AFA’s Mitchell Institute.

‘Shell Game’

The fragmented, atypical budget season has bewildered longtime defense watchers and left key players in the process searching for clarity.

Republicans and Democrats alike have criticized the administration’s reconciliation gambit as a “shell game” that presents the facade of a $1 trillion budget without a meaningful path to repeating it. Lawmakers’ frustration over not receiving the budget request by June was a constant refrain at hearings that were intended to delve into budget details.

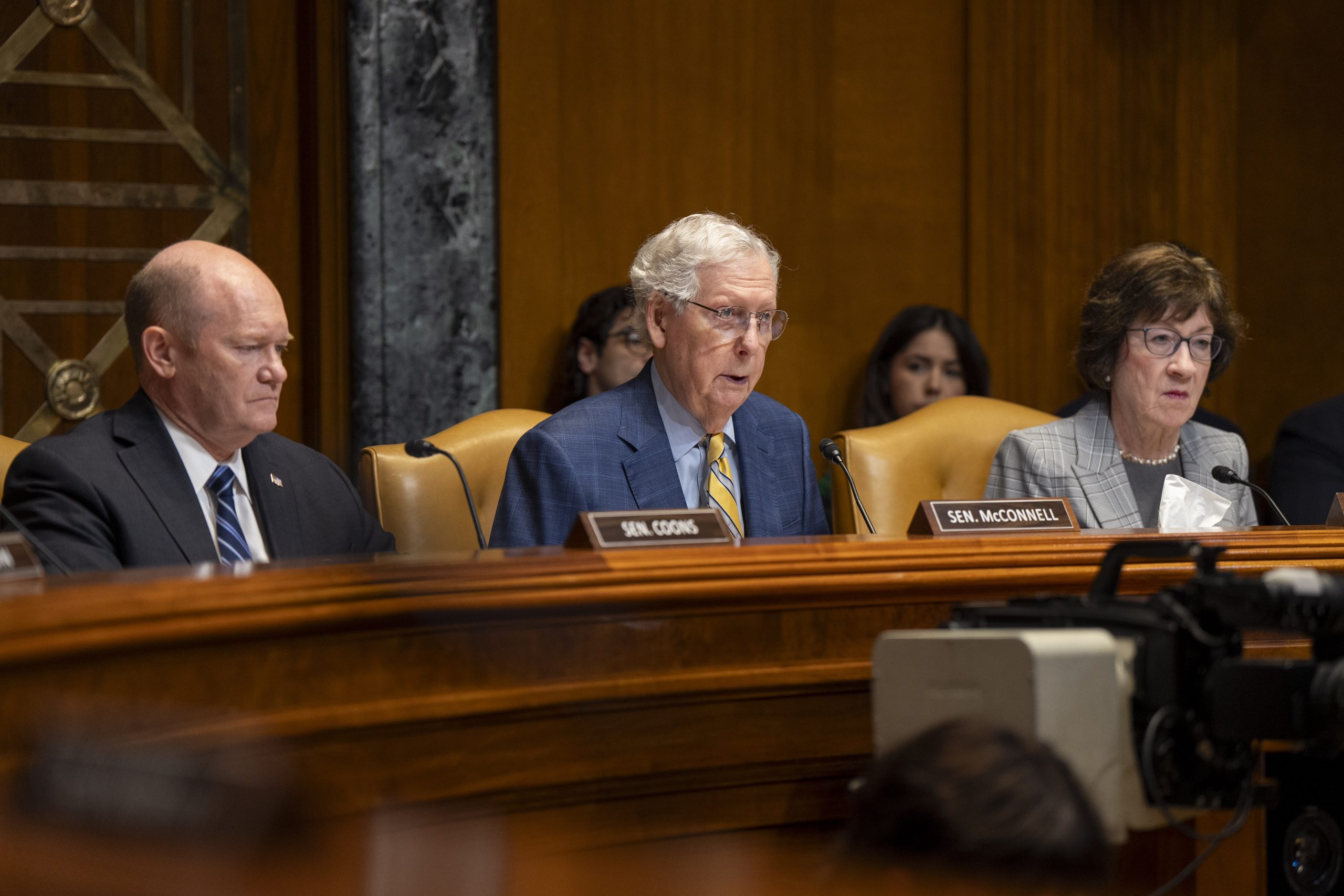

Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), the former Senate majority leader and defense hawk who chairs the Senate defense appropriations subcommittee, questioned Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David Allvin on why the Trump administration put programs with broad bipartisan support, like the B-21 bomber and Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, into the reconciliation bill rather than keep them in the base budget itself.

“I don’t fully understand all of the mechanisms,” Allvin answered, “but … a sustained topline to be able to continue our modernization and maintain readiness is going to be key, however that happens.”

Elaine McCusker, who was acting Pentagon comptroller during Trump’s first term and is now a defense budget analyst at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), said the unusual idea of using reconciliation to bolster defense was inspired by the supplemental spending bills that were nearly annual affairs through most of the 2000s. The move recognizes the long-term consequences of insufficient defense spending, she said, and was designed to get past the Senate filibuster rules and narrow vote margin.

“I think there’s goodness to it,” she said.

But she and others said offering top aerospace priorities a one-time bump is a risky maneuver that may not create the generational change the reconciliation bill sought to achieve.

Those programs need sustained funding through the base budget to succeed, observers said, especially new efforts trying to get off the ground.

“$25 billion … does a lot to get you started, but no one thinks you can build something [of] the magnitude Golden Dome is intended to be with $25 billion in one shot,” said Todd Harrison, a defense budget analyst, who works with McCusker at AEI.

Reconciliation dollars are also intended to speed up production of the secretive B-21. Slated to eventually become the Air Force’s primary bomber, it is unclear how much faster the acquisition can actually move. The B-21 is “manufactured differently,” Allvin said in June. “We don’t want to be overly zealous.”

Relying on reconciliation is particularly risky for the Space Force, which will take about half of its nearly $29 billion research-and-development budget from that pot in 2026. The Space Force won with reconciliation, Bingen said, but may struggle to sustain that level of investment.

“We think about all of the money tagged in reconciliation for space sensors, space superiority, [air moving target indication] from space, space infrastructure, space-based interceptors related to Golden Dome—there’s a lot in there for the Space Force,” she said. “Don’t get me wrong, it’s good, but you have to see a follow-through.”

Reconciliation will make it harder for military officials to plan for the future, especially when that money makes up a chunk of funding a program would otherwise have gotten through the more predictable base budget, Gertler said: “This is a one-time budget gimmick with lasting effects over many years.”

But McCusker suggested the maneuver could have one lasting benefit. She argues reconciliation has opened the door to treating more defense spending as mandatory, meaning the funds can continue past the end of a fiscal year. Doing so in the future could insulate funding decisions from the whims of lawmakers seeking to re-litigate decisions from prior years.

“We’ve been needing to have some modernization of the way we do defense appropriations for quite a while,” she said.

One enduring problem she’d like to see ended for good is the near-annual ritual known as a continuing resolution (CR). Those are necessary to avoid a federal shutdown when Congress fails to pass a budget by the start of the new fiscal year.

“If we can, at the same time, get away from the annual, destructive, wasteful nature of normal CRs, that’s all a good thing,” McCusker said.

What’s Next?

With only two months until fiscal 2025 ends Sept. 30, the Pentagon is on track to begin its seventh-straight year without permanent funding in place. Lawmakers have already started discussing the prospect of another stopgap CR to allow federal agencies to operate at the same funding level as they received the prior year.

Congress could also turn a CR into a slimmer spending package, as it did with its full-year stopgap legislation enacted for fiscal 2025 in March. In addition, reconciliation funding could also provide a bridge between fiscal years, McCusker said.

In recent years, the House and Senate passed and reconciled their respective defense policy bills in December, and appropriators followed soon after. Meanwhile, summer means the Pentagon has begun crafting the fiscal 2027 budget, and the top-line figure is an open question. Will Trump put forward the America’s first $1 trillion base budget plan for defense? Will Congress and the Trump administration get the budget process back on track?

“We have been so far from the regular order for so long that eventually this was inevitable,” Gertler said. “I don’t see anything out of this year that I would hope would become a norm. But it is foolhardy to wish for the regular order of the past that is likely never to return.”