The United States has a new defense strategy, built around smaller forces and a different set of assumptions.

The threat of a short-warning, global war starting in Europe, the scenario that drove US defense planning for more than forty years, is no longer central.

In the new scheme of things, potential conflict in Europe assumes the status of a major regional contingency. In both Europe and the Pacific, the old concept of forward defense gives way to “forward presence” with fewer US troops stationed abroad.

The Air Force will keep a few tactical or composite wings in Europe and the Far East. Both the Army and the Air Force will rely heavily on National Guard and Reserve units for the reinforcement of Europe.

By the mid-1990s, US active-duty military strength will drop from 2.1 million to 1.6 million. Six Army divisions, ten fighter wings, and 110 Naval vessels go also.

“We are planning to eliminate those forces–be they active or Reserve– whose justification has been based on the previous threat of short-notice global war,” Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney told Congress.

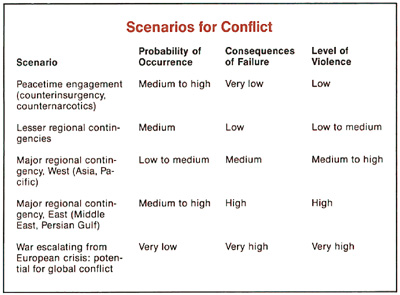

The big changes affect mainly the general-purpose forces and the planning for conventional conflict. The armed forces will be restructured for response to five general scenarios in which they might plausibly be required to deploy and fight. (See chart below.)

Fortunately, the most dangerous and difficult scenarios are the ones least likely to occur, but the Pentagon says that plans must take them into account because “the consequences of failure are so grave they cannot be ignored.”

Fewer adjustments have been possible in strategic nuclear aspects of US strategy because the Soviet buildup of strategic nuclear forces continues relentlessly. Five or six new long-range ballistic missiles are under development, and the prospect is that Soviet strategic forces will have been fully modernized by the mid-1990s.

The Pentagon estimates, however, that Soviet ability to project conventional power beyond its borders will continue to decline, whether by intent or as a by-product of economic troubles.

“We believe we will have sufficient warning of the redevelopment of a Soviet threat of global war so that we could reconstitute forces over time if needed,” Secretary Cheney says.

That concept-reconstitution of forces-is pivotal in the new strategy. Crisis response forces, reaching far and hitting fast, are supposed to handle “urgent” threats in “compelling” locales. Anything bigger would depend on mobilization, reinforcement, and other measures.

Global change is only part of the motivation for the new strategy. Bowing to the inevitability of deep budget reductions, the Pentagon devised the best plan it could with the limited funding and forces that will be available.

Delayed Debut

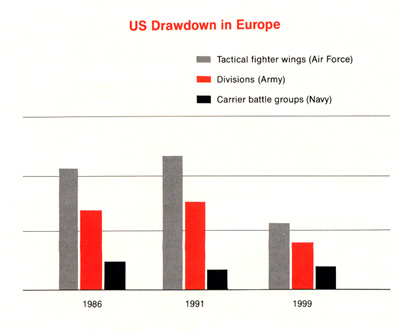

The Bush Administration was all set to begin telling the public about the new strategy last August. In fact, the President outlined it in a speech August 2, but the news that day was dominated by Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. The Gulf War over, Secretary Cheney and others have re-begun their explanation of a defense program that has been cut steadily since 1986 and will be reduced further by about twenty-five percent over the next five years or so.

The Pentagon declares that the new strategy represents its best judgment of threats and requirements, but at the same time, remains wary about how well this approach will work.

Secretary Cheney calls the outlook through Fiscal Year 1993 “a reasonably safe proposition.” Depending on how circumstances develop beyond then, he holds open the possibility of asking the President and Congress to reconsider the reduction plans.

In an unclassified version of the 1991 Joint Military Net Assessment, made public in April, the Joint Chiefs of Staff conclude that the revised defense program “provides minimum capability to accomplish national security objectives.” It has a number of weak spots, leading to “an overall assessment of moderately high, but acceptable, risk.”

Although the threat from the Soviet Union has lessened appreciably, the Joint Chiefs warn that “risk in the defense program is increasing because of key vulnerabilities emerging in the defense industrial base, underfunded R&D, sustainment shortcomings, strategic mobility shortfalls, and strategic defense deficiencies.”

If the United States had to fight two regional contingencies at the same time or back-to-back, there would be shortages in airlift, sealift, prepositioned equipment, and supplies.

When the Pentagon gamed its scenario for a major crisis in the Middle East, the results were disturbing. Once the Desert Storm forces pull out, it would take forty-nine days–a week longer than the time line allowed in the scenario–to put in all of the forces, equipment, and materiel required to handle the contingency.

“The continued erosion of defense capability, left unchecked, will undermine the foundations of the US force structure and preclude the fostering of US interests,” the Joint Chiefs conclude. “We are moving rapidly toward unacceptable risk.”

Secretary Cheney reminded a gathering of former Congressmen April I? that the 1 st Tactical Fighter Wing from Langley AFB, Va., which responded splendidly when Operation Desert Storm opened last year, did not look nearly so good a decade ago.

“Within fourteen hours, we had the 1st Tactical Fighter Wing, a significant part of it, on the ground in Saudi Arabia, ready to go to war,” he said. “Ten years before, the 1st Tactical Fighter Wing flunked its operational readiness inspection. Out of seventy-two aircraft in the wing back in 1980, only twenty-seven were combat-ready. The rest were hangar queens because of the lack of spare parts. If we do not make the right decisions as we go through the period immediately ahead when we’re building down the force, we’re going to wind up with exactly that kind of capability in the future.”

Forward Presence

Compared to forward defense, the official explanation says, “forward presence is less intrusive in its deployments and more flexible in its response to unexpected requirements.”

The difference would show up sharply in Europe, with perhaps half of the US forces pulling out by 1999.

Adm. David E. Jeremiah, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told the Senate Armed Services Committee April 11 that the final decision had not been made, but that he expected “the active component of the Atlantic forces will eventually include a forward presence in Europe of a heavy Army corps with at least two divisions, a full-time Navy and Marine presence in the Mediterranean, and Air Force fighter wings possessing the full spectrum of tactical capability.”

A chart Admiral Jeremiah gave the committee shows three Air Force fighter wings in Europe, backed up by two active-duty and eleven reserve fighter wings in the United States. “The bulk of the reserve components of the services have been allocated to the Atlantic forces,” he said.

“We will keep a continuous Naval presence in the [Persian] Gulf, and we expect to exercise ground and air forces there regularly,” Admiral Jeremiah added.

In the Pacific, the Air Force will station a few wings of fighters forward in Korea and Japan. The Army will keep one division in Korea. Otherwise, US presence will be the Navy and the Marine Corps, with reinforcements available from ground and air units in Hawaii and Alaska.

Four Army divisions, seven Air Force fighter wings, intertheater airlift, Naval forces from the Atlantic and Pacific, and special operations forces from all services will be employed as contingency forces.

“Because the emphasis in contingency response is on timeliness, the forces are versatile, primarily light, and drawn from the active components,” Admiral Jeremiah said. In addition to the fighter wings and airlifters, the Air Force will contribute conventional strategic bombers, command and control aircraft, intelligence platforms, and other assets.

The Active-Reserve Mix

The Air Force, which has always used its Guard and Reserve components far more effectively than the other services have, will take most of its reduction in active-duty units. By the mid-1990s, the tactical forces will consist of fifteen active-duty and eleven reserve forces wings, a considerably closer ratio than at present.

Army Guard and Reserve components will be cut substantially. Two of the six Reserve divisions will be eliminated, and another two will convert to “cadre” status. Cadre units would have a full complement of equipment but greatly reduced manpower and training.

Air Guard and Reserve forces performed very well in the Gulf War, as did many reserve units from the other services, but their overall image was shaken when some Army National Guard roundout brigades reported in sorry shape and could not be sent to the war zone without remedial preparations.

Secretary Cheney points out that a quarter million Guardsmen and Reservists were called up and “performed absolutely magnificently.” The only real problems, he says, were in three National Guard units.

“It’s not any condemnation by any means of the Total Force concept or for the role of the reserves at all,” he says. “What it does require is a minor adjustment in our assumptions about the readiness level of those ground combat brigades.” Among the early adjustments was firing the commander of one of the problem units.

The annual report of the Joint Chiefs states flatly that “our assessment concludes that Army RC (reserve component) round out brigades are not responsive to no-notice or short-notice contingencies.”

Reconstitution and Sustainment

In many ways, the success of the new strategy hangs on two big assumptions: that there will be adequate warning time to reconstitute forces if required and that the reconstitution concept will work.

The Joint Military Net Assessment says that “reconstitution may well prove to be the linchpin of America’s long-term security.”

The report says that US forces “are potentially inadequate in the long-warning, global-war scenario because of mobilization shortfalls in personnel, training, and the industrial base.” It cites sustainment shortages that include munitions, petroleum reserves, medical supplies, chemical-biological defense equipment, and various kinds of prepositioned stocks.

In an escalating European crisis, the Joint Chiefs project that “it would likely be six to twenty-four months before industrial base mobilization or surge production could begin to deliver critical items.”

With the defense industry in general decline, the Joint Chiefs are concerned that sources for some products “may shrink to unacceptably low levels.” The Pentagon relies on a dwindling handful of suppliers for such commodities as aircraft engines, radars, gun mounts, aluminum tubing, and optic coatings.

The Joint Chiefs estimate that by the end of 1997, “it would take two to four years to restore production capability to 1990 levels for items whose lines have gone cold.”

Even now, the Defense Department must depend on foreign sources for machine tools, precision ball bearings, computer chips, optical components, and other products (see table below). The extent of dependence on foreign suppliers is increasing steadily.

The limiting factor in several contingency scenarios is a shortage of airlift and sealift. In 1990, for example, the US had less than a third the number of militarily useful dry-cargo ships it did as recently as 1970.

For years, the Defense Department’s nominal goal for airlift capability has been 66 million ton-miles per day. The current capability, counting the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, is 48 million. When the Air Force fields the C-17 airlifter, capacity will rise to 55 million, somewhat lower than previous projections because C-17 procurement has been cut from 210 aircraft to 120.

The Technology Revolution

“For some time, the Soviets have been writing about a military technological revolution that lies just ahead,” Secretary Cheney told Congress. “They liken it to the 1920s and 1930s, when revolutionary breakthroughs, such as the blitzkrieg, aircraft carriers, and amphibious operations, changed the shape and nature of warfare.

“We have already seen the early signs of this revolution in the recent breakthroughs in stealth, information, and other key technologies,” he said. “Whatever we do, the Soviets and others will be pursuing this revolution diligently. Revolutionary military capabilities are a reality with which our future strategy must deal.”

At present, no country is ahead of the United States in any overall area of technology, but Joint Military Net Assessment (see chart) shows the Soviet Union with significant leads in some areas of pulsed power and Japan significantly ahead in some areas of machine intelligence and robotics, photonics, semiconductors, microelectronic circuits, superconductivity, and biotechnology.

If the trend continues, the Joint Chiefs foresee that “many countries, including potential adversaries, may threaten US technological superiority in many areas of potential military significance.”

The Defense Department investment in science and technology has declined over the past twenty-five years, even when the defense budget was rising. “Private industry has not been able to make up the difference,” the Joint Chiefs say. “The result has been a serious erosion in US technological leadership in the international community.”

Historically, about sixty-one percent of the defense budget has gone for operations and support of forces and thirty-nine percent to the investment account (procurement and R&D). Of the investment share, approximately thirty percent has gone to R&D.

Over the next five years, Navy R&D spending will follow the historical averages, and the manpower-intensive Army will be well below them. The strongest push for R&D will be by the Air Force, which plans to pour 47.4 percent of its resources into the investment account, trading force structure for force modernization.

Secretary of the Air Force Donald B. Rice told the House Armed Services Committee February 26 that, in the near future, getting off an accurate first shot will no longer be enough to win a fighter engagement. “We are rapidly moving into an age in which the other guy will get his shot off before the missile impacts him, and the result of that engagement is that both of you are dead,” Secretary Rice said. “That is the box we are moving into in air-to-air combat with the fighters that are currently being produced–not with the projected new generation of fighters–and that, we think, is untenable.”

It is not yet certain, however, that a thrift-minded Congress will actually allow the Air Force to spend the amounts it has earmarked for a new fighter and other development and force modernization programs.

Meanwhile, some of the regional contingencies described in the new strategy are becoming more difficult propositions. In a prediction he repeats often, Secretary Cheney says that “by the year 2000, it is estimated that at least fifteen developing nations will have the ability to build ballistic missiles–eight of which either have or could be near to having nuclear capabilities. Perhaps thirty countries will have chemical weapons, and ten will be able to deploy biological weapons as well.”

Elaborating on that in his April 17 talk to former Congressmen, Secretary Cheney said that “nobody in the developing world is likely to be able to match our technical sophistication in terms of precision guided munitions and stealth in the future, but what they are likely to do, and what may turn out to be the poor man’s low-cost military option, will be a relatively crude ballistic missile with a relatively crude warhead on top, but that’s enough to create real problems.”

|

|

|

Where Supplies Are Short | |||

| Product or item | Number of Suppliers | ||

| Airborne radars | 2 | ||

| Aircraft engines | 2 | ||

| Aircraft landing gear | 3 | ||

| Aircraft navigation systems | 2 | ||

| Aluminum tubing | 2 | ||

| Doppler navigation systems | 2 | ||

| Gun mounts | 2 | ||

| Image converter tubes | 1 | ||

| Infrared systems | 2 | ||

| MILSPEC-qualified connectors | 3 | ||

| Needle bearings | 2 | ||

| Optic coatings | 1 | ||

| Radomes | 2 | ||

| RPV/missile/drone engines | 2 | ||

| Specialty lenses | 2 | ||

| Titanium extrusions | 1 | ||

| Titanium sheeting | 3 | ||

| Titanium wing skins | 2 | ||

|

Although reconstitution of forces is a major theme of the new strategy, the defense industrial base continues to decline. The armed forces depend on a handful of suppliers for the items listed here, and the 1991 Joint Military Net Assessment says, “We do not have either the authority or the resources to ensure that even this level of infrastructure will remain in the future.” | |||