Space long has been critical to USAF’s intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance power. Because of this, the Air Force traditionally has sought top-of-the-line ISR space satellites, developed in-house at great cost in time and money.

Now, though, the service has come to realize that some of its space-based ISR could be provided by simpler satellites. USAF is hoping—and planning—to seek “good enough” capabilities that can be fielded faster and possibly at less expense.

The concept is deceptively simple: The military service would concentrate on fielding systems for only the most demanding and advanced requirements. For lower- and medium-level needs, it might rely on commercial satellite systems.

By addressing a narrower set of goals, USAF could reduce the complexity of its own work in the enormously difficult realm of designing and fielding advanced ISR satellites. Senior Air Force space leaders believe this approach might eliminate the problems inherent in building one-size-fits-all surveillance satellites, and yet still allow USAF to gain the benefits of the most advanced capabilities.

|

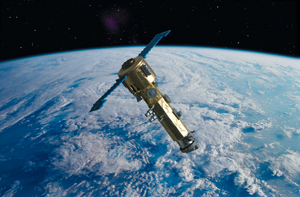

An artist’s conception of the SBIRS satellite. (Illustration by Erik Simonsen) |

The Air Force is also finding ways to use existing satellites in new ways, through software upgrades, new purposes for the data the spacecraft provide, and other adjustments.

Finally, some space-based ISR programs that were already well along in their development—such as the Space Based Infrared System—are performing beyond expectations.

It is enormously difficult to develop space-based ISR platforms, but the Air Force’s new approach should help mitigate some of the development problems seen over the past decade.

The Air Force recently boosted its ISR capabilities through two new SBIRS payloads carried aboard classified satellites. These early warning spacecraft scan the globe looking for ballistic missile launches—a mission important to protect the US homeland and American troops deployed overseas.

USAF has operated Northrop Grumman’s Defense Support Program satellites for the early warning mission over the past four decades. The next generation SBIRS was a long time coming, but is already starting to pay dividends.

Revolutionary Performance

The SBIRS program has been plagued by technical difficulties, driving up its cost by billions of dollars and delaying the launches of the dedicated satellites by at least seven years. Col. Roger W. Teague, commander of the SBIRS Wing at Space and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles, recognizes this but adds that the payloads in space today are performing better than expected.

“The performance has been revolutionary,” said Teague, who noted that the feedback from commanders who have used the data from the sensors has been strongly positive.

Raymond Yelle, command lead for ISR and ballistic missile defense at Air Force Space Command in Colorado Springs, Colo., said ground testing with the sensors indicated that they would be three times as sensitive as their specifications required. This was proved out in the operational trials.

|

Gen. C. Robert Kehler (l), AFSPC commander, and Col. Steve Tanous, 30th Space Wing commander, at Vandenberg AFB, Calif., site of USAF’s western launch range. (USAF photo by A1C Matthew Plew) |

The early warning satellites also monitor for other heat-generating events in the battlefield and elsewhere around the world. They can spot events as varied as exploding munitions and erupting volcanoes.

This gives the Air Force added confidence that the forthcoming SBIRS satellites will also perform as well on orbit as they have during ground testing.

The SBIRS payloads in space today pass over the Earth in highly elliptical orbits. The first of two SBIRS payloads, built by Lockheed Martin, was accepted by Air Force Space Command in November following initial checkout and operational trials.

Teague said the second payload is already providing useful data, and he expects Air Force Space Command to formally accept control of that bird in the spring. USAF plans to launch its own, dedicated, SBIRS satellites into geosynchronous orbits beginning in late 2009.

Ultimately, SBIRS will give the military advanced missile warning capabilities that include more accurate determination of an incoming missile’s impact point. This can help deployed forces limit the number of troops that need to take precautions to a smaller group actually threatened by the attack. (Protective measures, such as donning gear to protect against chemical and biological weapons can reduce productivity and slow work such as readying aircraft for takeoff.)

|

TacSat-2, already in orbit, features a variety of instruments, including a low-power imagery sensor and a signals intelligence payload. (Illustration by Erik Simonsen) |

SBIRS also offers improved sensitivity, which can help to spot mobile missile launchers like those used against the United States in Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom. That sensitivity can look for other things on the battlefield that generate heat, such as enemy tanks or trucks, and is useful for conducting bomb damage assessments.

The SBIRS sensors in space today employ an infrared sensor that scans the Earth looking for heat-generating events. The dedicated SBIRS satellites that are intended to follow those in orbit today will add a sensor that can stare at particular areas of interest for long periods of time.

Teague said that Gen. C. Robert Kehler, commander of Air Force Space Command, refers to this feature as USAF’s first space-based sensor for 24/7 persistent surveillance.

Leveraging Existing Assets

There is very little that can be said about how the staring sensor will be used for ISR purposes, but the ability to stare continuously at an area of interest, rather than scan the entire visible portion of the Earth, means that the dedicated SBIRS satellites will be able to spot targets—including those that generate less heat—much faster. This is an important improvement for missions such as finding and targeting mobile missile launchers.

Space Command is hoping to further exploit the SBIRS payloads that are on orbit today for battlespace awareness through the Operationally Responsive Space effort, Yelle said.

ORS is intended to find new ways to leverage existing assets to quickly meet urgent needs. The current wars have shown that traditional development cycles are much too slow to respond to emerging battlefield requirements.

In the case of the SBIRS payloads, Space Command would like to develop new software and other capabilities to work with their infrared data, Yelle said. There are “all kind of things” outside of ballistic missile launches that the Air Force may want to use the infrared sensors to look for, he said.

While roughly half of the ORS missions are ISR-related, responsive space capabilities are still a relatively small piece of the overall Air Force ISR workload. According to Lt. Col. Michael Grieco, deputy for the ORS division at Space Command, ORS’ role in providing surveillance capability is already significant and will likely grow over time.

When the ORS effort cannot leverage existing capabilities to meet emerging requirements, it develops satellites that can be launched on short notice.

To avoid the high cost and lengthy development time associated with most major space systems, satellites built under the ORS effort feature relatively mature technology, have a more narrow set of mission requirements, and are designed to operate on orbit for a relatively short period of time.

These parameters may not allow for a satellite as capable as standard systems such as SBIRS, but the Air Force is hoping that they can be good enough to fill in some capability gaps on short notice, or allow the military to reconstitute an existing constellation following an on-orbit failure or deliberate enemy attack.

Operationally Responsive Space advocates have high hopes for a number of upcoming efforts. ISR efforts under the ORS umbrella include ORS Sat-1, which will be built by Goodrich ISR Systems of Danbury, Conn., and is expected to launch in 2010.

|

An artist’s conception of the TacSat-3, which will feature a hyperspectral sensor capable of penetrating enemy efforts to camouflage potential targets. (Illustration by Erik Simonsen) |

ORS Sat-1, the first satellite developed under the ORS program for operational purposes, will feature an optical sensor based on a design that the company has used on the U-2 surveillance aircraft.

The Air Force is reluctant to talk about the details of ORS Sat-1 publicly, but has acknowledged that the satellite is intended to meet an urgent ISR requirement for US Central Command.

Air Force ISR capabilities could also be boosted by use of the experimental TacSat-3 spacecraft expected to ride into space in 2009. This launch date has already been postponed several times, however, for a variety of factors. These have included difficulty securing funding for the satellite platform and the need for additional work to protect the satellite’s sensor from vibration during launch.

TacSat-3 will feature a hyperspectral sensor built by Raytheon Space and Airborne Systems of El Segundo, Calif. This will give the Air Force the opportunity to experiment with the ability to use the vantage point of space to look down and penetrate enemy attempts to camouflage potential targets. The need for this capability emerged on commanders’ wish-lists following battles in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Some of the targets that could be uncovered with hyperspectral imaging include vehicles, buildings, and landmines.

Data from the TacSat-3 experiment will be used as the military weighs the possibility of launching a constellation of satellites with similar sensors. The experimentation is also intended to give commanders the opportunity to try new methods of tasking, processing, exploiting, and disseminating the data.

Once the experimentation with TacSat-3 concludes, the Air Force hopes the spacecraft will be able to do still more. Study work is going on now, investigating other possible uses for the satellite, Grieco said.

The Air Force has already launched one satellite—TacSat-2—under the ORS effort. TacSat-2 featured a variety of instruments, including a low-power imagery sensor that commanders could point at areas of interest and a signals intelligence payload.

In addition to demonstrating the utility of those payloads, TacSat-2 gave the military the chance to begin experimenting with the ability to task the small satellites and receive information within 90 minutes.

The Air Force could ease the ability for commanders to take a closer look at the ground as they prepare for battle by stockpiling ORS satellites and the small rockets needed to launch them in order to be better prepared for urgent needs that may arise.

Joint Ownership

The Air Force could further develop its space-based ISR muscles in the near term through taking a revised approach in the radar arena.

The Air Force has been working with the National Reconnaissance Office for the past decade in an effort to develop and field the Space Radar satellites, which would offer the ability to maintain surveillance regardless of time of day or weather conditions.

The Space Radar satellites were initially envisioned as a large constellation that could provide continuous tracking of moving targets on the ground as well as high-resolution imagery. However, the concept has been repeatedly scaled back, and little progress has been made in getting the satellites off the ground due to a lack of cooperation between the Air Force and its Intelligence Community partners and a struggle for funding on Capitol Hill. Space Radar, as originally conceived at least, appears to be dead after Congress eliminated all funding last year.

|

Kehler has called SBIRS the Air Force’s first space-based sensor for 24/7 persistent surveillance. (USAF photo by Duncan Wood ) |

Fed up spinning its wheels, the Air Force is now looking at ways to achieve at least some of the imagery goals hoped for with Space Radar by 2012 by relying on currently available technology.

This could come through a mix of government-owned satellites and commercial services such as those operated today by foreign partners.

Yelle said Space Command has examined foreign-owned capabilities in response to this directive, including the Canadian Radarsat-2 satellite. Other foreign commercial radar systems that experts say could help the Air Force meet its needs in this area include the German SAR-Lupe satellite constellation.

Space Command is also looking at how a small set of military-owned satellites could be developed to meet the needs of US forces that commercial systems cannot handle, Yelle said.

Whether those satellites would be built in partnership with the National Reconnaissance Office is still under discussion. Alden V. Munson Jr., the director of national intelligence’s top acquisition official, recently said, however, that if the Pentagon decides that its needs can be met with a “more modest” capability that lacks “exquisite” resolution, the Intelligence Community will go its own way.

“It’s a reasonable conclusion that we have capability, that we’re thinking of what to do next, and that we’re comfortable with those plans,” Munson said.

|

Watching the Weather The Space Based Infrared System payloads in space today have gathered data on a variety of heat-generating events, including missile launches, wildfires, and volcanoes. During the operational trials, the Air Force discovered that the SBIRS payloads can perform weather monitoring, a mission not envisioned for the program when it began in the late 1990s, said Col. Roger W. Teague, commander of the SBIRS Wing at the Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center at Los Angeles AFB, Calif. Weather prediction is an important component of ISR. The weather can be a deciding factor when commanders plan to launch a mission, or perhaps to hold off for several hours. Commanders may even abort missions if severe conditions could interfere with actions such as dropping bombs, said Raymond Yelle, command lead for ISR and ballistic missile defense at Air Force Space Command. The Air Force operates dedicated satellites for this purpose. The Defense Meteorological Satellite Program constellation was first launched in 1962 and is expected to be replaced in the next decade by the National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System. NPOESS is a joint effort with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. |