The torture process, known officially as the full-scale durability test, will discover if the F-16 fleet, already five years beyond its originally planned retirement date, can serve well into the 2020s. The Air Force is betting it can, and is preparing a series of upgrades intended to keep the Falcon credible and capable right up until it is withdrawn from service.

A similar fate awaits an F-15C and, later, an F-15E, which will both undergo full-scale fatigue testing (different name, same process) at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. A comparable A-10 stress test is already under way. The predicted longevity of these fighters will significantly shape USAF’s choices in the next couple of years.

Planning the golden years of the Air Force’s legacy fighter fleet has taken on great urgency, given the new realities of fighter modernization. Production of the F-22, which was to have completely replaced the F-15, was capped at 187 aircraft. The F-16’s replacement, the F-35, has seen schedule delays and cost jumps that have made it a target of various panels and think tanks offering deficit-cutting advice. Although the Air Force and Pentagon strongly back the fighter, budget pressures or test delays could further stretch out deliveries.

|

Two F-16s pass near the Grand Canyon on a training mission from Luke AFB, Ariz. How long the F-16—already five years beyond its original planned retirement date—will last is an important question USAF is attempting to answer. (Photo by Jim Haseltine) |

The Government Accountability Office, in a summer 2010 audit, said that even if the Air Force is able to buy F-35s at the rate of 80 per year—which the GAO found dubious at best—the service will fall further and further short of the 2,000 fighters necessary to fulfill the national military strategy. That means some of the old fighters will have to be kept in service simply to keep the Air Force in business.

Besides the F-15C, F-15E, and F-16s of various block numbers, the Air Force will also hold onto hundreds of A-10 attack aircraft, made in the 1970s and 1980s, for at least another 20 years.

“Should the F-35 not deliver on the anticipated schedule, … there are potential work-arounds,” said Gen. Norton A. Schwartz, Chief of Staff of the Air Force.

Speaking with defense reporters in November, Schwartz said, “Certainly we will look at sustaining F-16 aircraft—principally Block 40 and Block 50 aircraft—perhaps a bit longer than we had originally planned.” There would be structural modifications as well as avionics improvements, to include new, advanced radars, he said.

He emphasized that the Air Force is “fully committed” to buying the F-35A, the progress of which has been “the best of the lot” compared with the Marine Corps F-35B and Navy F-35C versions in flight test.

However, “you have to hit the ball where it lays, and if the airplanes aren’t ready to put on the ramp, we’ll work alternatives. … We’ll do what’s required.”

|

Two A-10s fly a two-ship formation during training at Moody AFB, Ga. The Air Force plans on holding on to hundreds of A-10s produced in the 1970s and 1980s for at least another 20 years. (USAF photo by A1C Benjamin Wiseman) |

Schwartz said that in the Fiscal 2012 budget, a “fighter force structure strategy” document would accompany information about the F-35’s progress.

The Air Force is trying to find the right balance in deciding how to fill out its fighter inventory, said Maj. Gen. Thomas K. Andersen, Air Combat Command’s director of requirements.

“We do have that struggle: Do you trade off capacity for capability?” he said. On the one hand, the Air Force must have enough aircraft to go around to meet field commander needs, which is capacity. On the other, the fighters must have technology relevant against adversaries with increasingly advanced aircraft—capability.

“Those are things that we try to inform every day,” Andersen said.

The Air Force’s “wish list” for improving its legacy fighters is specific to every aircraft, but some items are deemed essential to all.

To remain credible against modern, generation 4.5+ fighters, both the F-15 and the F-16 will need active electronically scanned array radars, better known as AESAs. The benefits of such radars are many. They can perform several different functions simultaneously, from searching the air for enemies to doing ground-mapping and detection of moving surface vehicles. Because the radar can rapidly hop frequencies, its emissions are less detectable and this improves aircraft survivability.

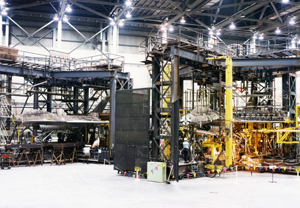

|

Two early F-16s undergo full-scale durability tests at a Lockheed Martin facility in Fort Worth, Tex. When something important finally breaks, USAF will have vital information about upgrades necesssary to keep the F-16 flying. (Lockheed Martin photo) |

Solid-state digital systems, AESAs have very high reliability. In fact, once installed, AESAs have a mean time between failure rate rivaling the life expectancy of the aircraft itself. So reliable are they—and so able to degrade gracefully even if some parts go bad—that the aircraft radome could potentially be sealed shut. The virtual elimination of service requirements on radars would dramatically reduce the man-hours needed for maintenance of fighters while dramatically enhancing their capability.

Big Incentives

“There’s a lot of great [radar] technology we’ve been working on with the F-22 and F-35,” Andersen noted. “We’d love to pull some of that capability into an AESA radar for the F-16.” He said, “We’ve paid for that nonrecurring engineering” on AESA radars for the fifth generation fighters, and there are “a couple of offerings out there that are relatively inexpensive.”

Another improvement becoming more common in the fleet is helmet mounted cuing systems. These devices enable fighter pilots to simply look in the direction of a target and in so doing, tell a missile where to go once it leaves the launch rail. The system relieves the pilot of having to point his aircraft directly at an enemy fighter before firing, a valuable asset in a dogfight.

To deal with stealthy targets, the Air Force will likely put infrared search-and-track (IRST) devices on its fighters, so the aircraft can see the faint heat plumes of engines even when a target has reduced radar reflectivity.

Beyond sensors and targeting systems, the legacy fleet will need upgrades to its suite of electronic warfare equipment, as well as new air-to-air weapons that can target enemies at greater distances, are less prone to spoofing, and are more agile. The Air Force is counting on the latest version of the Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile, or AMRAAM, called the AIM-120D, for its future air superiority missile. For ground attack, fighters will need smaller munitions that can inflict extremely precise damage and destroy only what they’re supposed to. The Small Diameter Bomb Increments 1 and 2 are the principal munitions in this latter category.

|

Capt. Jim Parslow inspects a weapons carriage on an F-15E loaded with a GBU-39B Small Diameter Bomb. F-15Cs and, later, Es also will undergo full-scale durability tests at Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio. (USAF photo by SrA. Ricky Best) |

There’s a big incentive to fix up the older airplanes until new generation aircraft can be fielded. Schwartz has consistently and categorically said the Air Force will not spend scarce fighter dollars to buy new versions of older aircraft—i.e., to buy new-build F-15s and F-16s. The Air Force would rather stretch its existing equipment and wait for cutting-edge airplanes than buy new airplanes with 40 years of service life but only 10 years of survivability.

The GAO, in its summer 2010 report on fighter forces in all the services, said, “Recently, the Air Force provided Congress with a report titled ‘Procurement of 4.5 Generation Fighter Aircraft,’ which concluded that modernizing and extending the service life of current fighters would provide essentially the same capability of new 4.5 generation fighters at 10 to 15 percent of the cost.” The estimate was based on buying 300 new aircraft of the F-16 Block 50+, F-15E+, or F/A-18E/F vintage or performing a service life extension on a similar number of existing airplanes. The Air Force looked at doing structural improvements only, or structural and capability enhancements combined.

The estimates, however, don’t have the benefit of the fatigue testing to be done on the F-16, F-15C, and F-15E. While the Air Force thinks it has a pretty good idea how long the airframes can last, there could be considerable surprises in the destructive testing that radically alter estimates.

However, Andersen doesn’t think that will be the case. For the past few years, USAF has been monitoring fighters by tail number, keeping track not only of how many hours they have flown, but what kind of hours: An hour spent ferrying across the ocean is very different from an hour of hard-turning air combat maneuvering. This effort is known as the Aircraft Structural Integrity Program, or ASIP. Besides the severity of missions flown, basing has a lot to do with aircraft longevity. Andersen noted that aircraft operated for years in the dry Southwest have more potential life than those flown in humid, salty conditions.

“If you take the ASIP … and you put it together with the full-scale durability testing, we’re going to have a pretty good idea of what the life of the F-16 is going to be,” he said.

The “pre-blocks” of F-16s, he said—those early vintage Block 25s and 30s—will be allowed to age out of the inventory when they reach about “10,800 equivalent flying hours.” They were originally specified for 8,000 hours.

For the long term, he said, the Air Force is concentrating on the Block 40s, 42s, 50s, and 52s. All these aircraft have completed the Common Configuration Implementation Program, or CCIP, which largely standardized F-16s with a similar cockpit configuration, software, modular mission computer, helmet mounted cuing systems, and the Link 16 data link.

In addition to the AESA radar upgrade, F-16s would get new weapons: the AIM-120D, Small Diameter Bomb Increments 1 and 2, and potential future weapons such as the Joint Dual-Role Air Dominance Missile, or JDRADM.

Learning From Failure

The durability test will be done on a Block 50 considered to be representative of what the fleet has typically endured. It will be stressed to an equivalent of 24,000 hours of flying, assuming it doesn’t suffer a fundamental failure before that point. The Air Force traditionally tests to double the anticipated usage of the airplane, so if the test article achieves 24,000 hours without a major structural failure, USAF believes it can get 12,000 flying hours out of line aircraft, Andersen explained.

“We’re fairly confident” of the 12,000-hour number, Andersen said. “So if you look at those numbers conservatively, that’s about another perhaps seven to eight years of service life” on the Block 40s to 52s. That would be on top of the additional years of life “bought” by monitoring the aircraft individually.

The Air Force has already performed a structural improvement on some F-16s called Falcon STAR, but this was intended to get them to their originally planned service lives. The F-16s, which saw extensive combat from Desert Storm in 1991 to today, were used harder and carried heavier loads than first expected; this caused stress fatigue in some components and cracks in some bulkheads. Falcon STAR—for Structure Augmentation Roadmap—was not meant to be a service life extension program, or SLEP.

|

SrA. Rebeca Hill (top) and SrA. Christopher Jaeger work on an F-16 at JB Balad, Iraq. The F-16’s planned replacement, the F-35, has fallen prey to schedule delays. (DOD photo by SrA. Julianne Showalter) |

Without a SLEP, ACC thinks that “a small number” of F-16s could make it to 2030, but most will be “gone by 2025.” With a SLEP—which would reinforce or replace bulkheads, some spars, and add maintainability improvements overall—an F-16 fleet of about 300 airplanes could make it “to about 2030 to 2035,” Andersen said.

One thing that likely wouldn’t feature in an F-16 upgrade is the set of overwing, conformal fuel tanks that distinguish late-model F-16 Block 52s and 60s being sold overseas today.

“As of right now, we don’t have a requirement for it,” Andersen said.

Lt. Gen. Philip M. Breedlove told reporters in November the Air Force is going to look at the F-16 fleet “almost on a tail-by-tail basis to determine how many and what type” it needs to SLEP. But “we have to address a threat that continues to become more and more capable,” said Breedlove, deputy chief of staff for operations, plans, and requirements.

A fatigue test was ordered for the F-15C after an Air National Guard Eagle broke in half during a practice dogfight in 2007, leading to a months-long grounding of the F-15C/D fleet. The problem was a failure of longerons expected to last the life of the airplane, but the F-15 has served well beyond its planned lifetime. A series of inspections and some repairs cleared the fleet to return to duty, but the test is considered essential in getting the full story of what F-15 maintainers can expect as the aircraft continues to age.

The Air Force plans to retain 176 F-15Cs. Only two units—one at Kadena AB, Japan, and one at RAF Lakenheath in Britain—will serve with the active duty. Some 54 F-15Cs are on contract to be fitted with an AESA radar, and all F-15Cs are now fitted with the Joint Helmet Mounted Cuing System. The F-15Cs will also receive an IRST system to detect stealthy targets.

The F-15 fatigue test is “on contract,” Andersen said but lags the F-16 test by “about a year and a half.” It is planned to run from Fiscal 2012 to 2015. Assuming no big surprises show up in the test, “we could keep them well past 2025, into about the 2030 time frame,” Andersen said.

Likewise, the Air Force has decided to do a stress test on an F-15E Strike Eagle. It will begin about a year after the F-15C test gets under way. A specific aircraft to undergo the test hasn’t been chosen yet, but one will have to be sacrificed.

Unlike the F-15Cs, which will phase out in the next 15 to 20 years, the E fleet is expected to serve another 25 years or more. The aircraft was built later, with tougher, heavier load-bearing structures in order to carry a heavy attack weapons load. That, and expected use of lighter ordnance, should mean the Strike Eagles can make it into the late 2030s.

No Blanket Upgrade

Like the F-15C, Andersen said the E models will get an AESA radar—the APG-82—plus all the other enhancements. Right now, helmet mounted sights are only funded for the front seat of the two-seat airplane, but ACC wants to fit backseaters with the JHMCS as well.

The A-10 fleet is in the midst of a billion-dollar upgrade in which the aircraft that USAF will retain are getting new wings. At the same time, these aircraft are receiving the precision engagement package, giving the airplane new displays and a digital backbone to allow it to carry most of the most modern munitions in the inventory. About the only air-to-ground weapons the A-10 will not use are Small Diameter Bombs.

The new wings and structural improvements will boost the A-10’s life expectancy from 16,000 hours to 20,000 hours, buying it a place in the inventory until about 2035. The GAO reported that ACC thinks a helmet mounted cuing system is the “No. 1” upgrade needed to make the A-10 more effective, on top of the improvements already in the pipeline. Software development also is a key requirement for the A-10.

Funding will be a critical issue affecting upgrades of any kind. The Air Force sharply reduced its fighter inventory in the last two years, under what was called the Combat Air Forces Reduction, or CAF Redux. This saw some 250 fighters retired early, the savings meant to be plowed back into fighter force modernization. No F-15Es went away as a result of the CAF Redux, however.

“We didn’t touch the E fleet,” Andersen said, “basically, because it has unique capability.” In addition to its ground-attack role, the F-15E will also be fitted with the AIM-120D, “so it will have air-to-air capability. … It will be a multirole aircraft,” Andersen noted.

|

A GBU-39B Small Diameter Bomb strikes a rocket launcher during tests at White Sands Missile Range, N.M. SDB Increments 1 and 2 are being integrated into the F-16 fleet. (USAF photo) |

However, Marine Corps Gen. James E. Cartwright, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in December that he feared budget-cutting pressure would steal away some of the savings generated by moves such as the CAF Redux and a Pentagon-wide initiative to save $100 billion over five years by reducing overhead.

In November, ACC Commander Gen. William M. Fraser III said the money issue could mean that only selective parts of the fighter force get modified.

“If I have aircraft that are principally back here flying air sovereignty alert, they do not need to be exactly the same as our F-16 Block 40s and 50s,” Fraser said, because the ASA mission is typically more benign than the ground-attack missions over hostile territory that the rest of the F-16s would have to be able to do.

Breedlove echoed Fraser, saying, “What we are not going to do, I am relatively sure,” is create a blanket upgrade program for every F-16. “That’s not what we need,” Breedlove said. Some aircraft, with missions such as Operation Noble Eagle, require certain kinds of capability; other aircraft facing “the more challenging digital threats that are out there in the world may need a different kind of capability, and that’s the analysis that we’ve embarked on.”

The Air Force is working closely with the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve on upgrade programs because USAF recognizes that the reserve components’ F-16s are aging out and that its equipment must be comparable to that in the active force.

“We all want to get this right, because, as you know, the iron moves back and forth—some down to the Guard and Reserve and even in some cases from them to the active duty,” Breedlove said. “So we have to make sure that we have the right capabilities in each.”