The Department of the Air Force does not consistently or systematically ask Airmen or Guardians how dormitory conditions affect their quality of life and readiness, which reduces the department’s ability to identify and prioritize improvement efforts, according to a Government Accountability Office study published Sept. 19.

The other branches face similar issues: GAO found each has serious flaws in how they assess barracks systems, such as electrical, plumbing and foundation; in how they track and report barracks construction or renovation funding; in how barracks conditions affect residents, and in their rules for who is required to live in barracks. Junior enlisted, unmarried Airmen typically live in dormitories, which other services call barracks.

The study found that the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD), which oversees the services, must also play a larger role in guiding and standardizing barracks assessment programs.

“[T]he military barracks program is a large entity that spans all four military services, and improving barracks conditions requires OSD oversight and collaboration with OSD and military service leadership,” GAO wrote. “However, OSD has not provided sufficient oversight of housing programs for barracks.”

Many barracks, which the GAO used as a catch-all term to include Air Force dormitories, are in need of improvement. In their visits to 10 installations, investigators found a range of substandard conditions that affected service members’ mental and physical health, including:

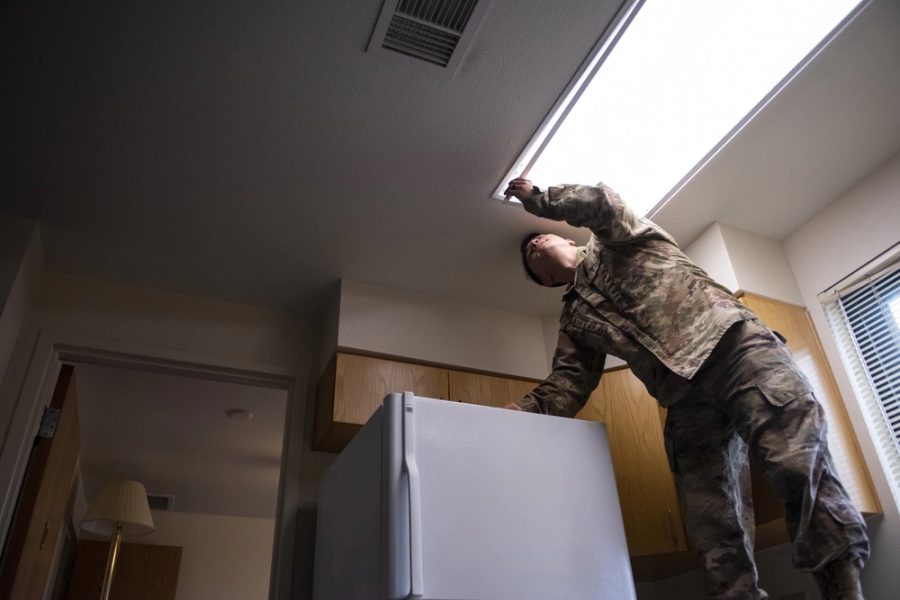

- All 10 installations reported broken, malfunctioning, or non-existent heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning systems. One service member said trying to sleep in a room without HVAC was “like standing in the sun all night,” while others in colder climates bought portable space heaters despite the fire risk.

- Broken or malfunctioning fire safety systems at four out of 10 installations

- Insufficient lighting, vacant units occupied by unauthorized personnel, or no existing or working security cameras at seven out of 10 installations. Two installations reported incidents of squatters living in vacant barracks rooms.

- Broken door locks and first-floor windows at three installations, which made several service members feel physically unsafe at night.

- Mold or mildew growth in occupied and vacant rooms in five out of 10 installations

- Water quality problems at five out of 10 installations. One installation reported the barracks tap water is often brown

- Pests such as bedbugs, rodents, cockroaches, and wasps reported by service members in six of 12 discussion groups

- Lack of privacy and insufficient space reported by service members in 10 out of 12 discussion groups, which they said affected their mental health and work performance.

The GAO did not specify which services the affected installations belonged to, but military housing writ large has a history of problems with maintenance and oversight. Many headlines concern private military family housing, but mold, roof leaks, and broken air conditioning remain issues in barracks as well, which can disrupt service members’ sleep, mental health, and ability to do their jobs. Those problems can also affect Air Force dormitories, despite the branch’s reputation for cushy living conditions.

“We had to lower standards for field training to keep [service members] mentally in the game,” one senior enlisted service member told GAO. “Had to do it because when they get out of ‘training’ they can’t take a hot shower [in the barracks], or sleep with a locked door.”

One barracks resident asked “if you can’t expect leadership to fix immediate housing issues, why stay [in the military]?”

While the Navy and Marine Corps conduct annual tenant satisfaction surveys for government-owned barracks, the Army and the Air Force do not. Air Force officials told GAO that they sometimes administer surveys at the installation level, such as informal exit interviews or unit commander surveys, but there is no consistent, standardized system which might inform Air Force-wide improvements.

The services already conduct tenant satisfaction surveys for private and government-owned family housing, so GAO called on OSD to direct the services to expand that survey to barracks. According to GAO’s analysis of military data, more than 148,000 Airmen and soldiers lived in barracks across the U.S. in fiscal year 2022.

“Army and Air Force leadership, in particular, may be unaware of effects on quality of life stemming from living conditions in barracks, and may not be positioned to make improvements for the thousands of service members required to live in barracks,” the authors wrote.

The GAO also called on the services to unify their standards for assessing barracks conditions, which vary widely in terms of what systems are inspected, how often they are inspected, and the expertise level of the inspector. The index used to score conditions may also be in need of an update: GAO analysis showed that nearly 50 percent of Air Force dormitories considered at-risk of significant degradation had a condition score of 80 or above.

Exacerbating the problem is the fact that the Defense Department does not track complete or reliable information on how much money is used to improve barracks conditions, how much more is needed to meet minimum standards, or what funding streams the money taps, GAO wrote.

In all, GAO made 31 recommendations to the Defense Department and the services to provide guidance on assessing barracks conditions; find complete funding information; and improve oversight of barracks. The Defense Department concurred with 23, and partially concurred with eight, citing ongoing actions to address some of them. GAO insisted the department should fully implement all 31 recommendations.