ANDERSEN AIR FORCE BASE, Guam—Aeromedical evacuation Airmen are preparing for future conflicts where scores more wounded troops will be in worse condition after being cut off from higher-level medical care by enemy air defenses.

That means Airmen must be ready to treat patients with fewer resources and no way to call home for advice—a new challenge after decades of aeromedical evacuation (AE) missions in the Middle East.

“There’s this pivot to provide our medics training that is very similar to what we’ll see in a large-scale combat operation,” said Lt. Col. Darrell Lee, AE branch chief at the training and readiness directorate at Air Force headquarters.

“We’re going to move larger patient loads, we’re going to have distributed ops where we’re island-hopping and trying to evacuate patients really quickly out of certain areas, but those patients are going to be a lot sicker than what we’re used to,” Lee said.

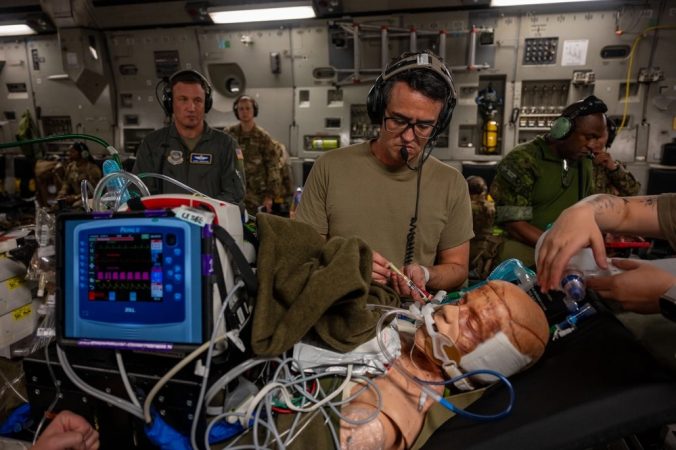

AE units are comprised of military doctors, nurses, medical technicians, and other health care providers who keep patients stable aboard aircraft on their way from the battlefield to higher-level care. Over two decades of counterinsurgency operations in the Middle East, AE crews usually worked with small numbers of patients who were injured just a few hours beforehand. Aboard the flights, crews generally had clear lines of communication to specialists on the ground and relatively short flights to Europe or elsewhere in the Middle East.

But in a conflict against adversaries such as China, whose advanced air defenses could keep air transport at bay, it may take weeks to pick up wounded troops, military health officials predict. The field hospitals that would act as first responders keep smaller supplies of blood, antibiotics, and other equipment on hand, putting injured service members at greater risk of complications such as infection and severe blood loss without more comprehensive care.

These lessons are already playing out in the war in Ukraine, where wounded soldiers stuck at the frontlines are dealing with antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections, limited blood supplies, and limb death caused by prolonged use of tourniquets, which cuts off circulation.

On top of that, enemy forces could disrupt America’s long-range communication networks—severing ties to specialists, interrupting information relayed about patients’ conditions, and forcing AE units to adapt on the fly. That means Airmen will have to figure out how best to handle a situation on their own without approval from higher-ranking colleagues.

“Whether you amputate or do some kind of surgical intervention or damage control surgery, you’re going to have people who haven’t had that experience making those decisions,” Lee said.

At a massive Air Force exercise across the Pacific this summer, American AE crews and their foreign counterparts practiced responding to mass casualty events that are more dynamic than a typical mission.

“We’re going to empower our medical crew directors to say, ‘Hey, you have these patients at this site. Who do you take on? Who do you leave behind?'” Lee said. “That’s different from [counterinsurgency operations], because those were all regulated missions, like, ‘These are the patients we’re giving you, you should expect this.’”

The training took place in Pacific hubs including Japan, Australia, and Guam as part of the Department-Level Exercise that began July 8. Some 12,000 Airmen and Space Force Guardians are practicing strike, transport, refueling, AE, and other missions alongside other U.S. armed forces and America’s foreign allies and partners, as they would if the U.S. went to war with China.

Major training events like this are important for AE squadrons, which don’t always have the resources to put on a mass casualty scenario involving 30 or 40 patients, Lee explained. Large exercises also help with the Air Force’s new force generation model called AFFORGEN, which aims to prepare units for combat over the course of 18 months before they become available for real-world taskings for six months.

“We’re relying on these soon-to-be certification exercises to say, ‘Hey, you guys are ready to go,’ or ‘Hey, you need more work on this,’” Lee said. That’s a change from the COIN years, which had more on-the-job training since most flights were regulated missions with clear expectations of patient conditions.

“Now we have to give them that training before they get out the door,” Lee said.

Large-scale training also provides opportunities to work with foreign partners and allies, without whom the U.S. would struggle to respond across a battlefield as vast as the Pacific.

During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, “we could dedicate an entire plane, multiple crews and air refueling to move one person all the way back stateside,” said Col. Jennifer Cowie, deputy for aeromedical evacuation in the Air Force’s training and readiness directorate.

“Over here, you probably are not going to have the resources to dedicate to something like that,” she said. “That’s where relying on our partners for shorter flights to a country nearby would be helpful.”

At the exercise, U.S. Air Force AE crews sought to more easily integrate with their counterparts from Japan, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

“Opportunities like this, where we get to train with those different forces, expose our Airmen to what other countries use, will make it a lot easier in a high-pressure scenario where that might be all you have left because all your crews are out flying,” she said.

Besides building connections with partners, the AE field is developing “algorithms,” or flowcharts to guide crews through the process of deciding treatment when comms are down.

For example, if a patient with respiratory failure rapidly deteriorates, an Airman would usually call a flight surgeon to ask for advice.

“If you don’t have that, this algorithm will walk you through exactly what you do, from something as simple as providing oxygen” to intubation, Lee said.

But there’s no blueprint for handling the psychological strain of not having enough time or resources to save everyone—almost guaranteed in a major war. A 2023 wargame run by the Center for Strategic and International Studies concluded that about 3,200 U.S. troops would be killed in just three weeks if America responds to a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. That’s about half as many American service members as were killed in Iraq and Afghanistan over two decades.

“It’s a hard pill to swallow” in a career field dedicated to saving lives, said Cowie, who recalled seeing Airmen in tears after a recent exercise in Maryland where AE crews could not save every patient.

In the near future, the AE field may partner with private companies to develop virtual or augmented reality training designed to prepare crews for those moments and practice doing the most good with limited resources.

“We need to develop something effective that will prep them psychologically and give them that resilience they need if something does happen,” Lee said.

Then there’s the physical fatigue: the lieutenant colonel said AE Airmen may develop something similar to so-called “maximum endurance operations,” where transport and tanker crews fly marathon sorties stretching 24 hours or longer, to prepare crews for long-haul flights over the Pacific.

Beyond training, Lee and Cowie hope the AE field can revamp how it presents forces in a crisis. The current process fragments aeromedical evacuation troops into six categories, which all deploy differently. That sometimes leads to crews arriving in theater 30 days before their gear.

That wasn’t a big deal over the past 20 years of fighting in the Middle East, since troops could pick up gear as they hopscotched between established bases on the way to the front lines. But it could be a problem in an unpredictable Pacific fight.

“What we’re trying to do is bring those puzzle pieces together, so … we flow with our equipment, so that we are not going to be 30 days late to the ball game,” Lee said.