AirSea Battle, the operational concept recently assembled by the Air Force and Navy, is an ambitious effort with great implications for how the air and sea services plan for, equip, and prepare to fight future high-intensity conflicts.

Months ago, its anticipated rollout seemed imminent. But today, AirSea Battle’s relevance, as currently constructed, is uncertain. Daunting budget challenges now call the US military’s modernization efforts and technology pursuits into question. Critics have targeted the Air Force’s next bomber, and concerns about the health of the Navy’s fleet have emerged. AirSea Battle, in whatever form it finally emerges, will rely heavily on warships and long-range airpower.

ASB is born out of a need for the US military to address perceived threats and strategic concerns across the globe, in environments far different from the two largely “low intensity” wars fought over the last decade.

|

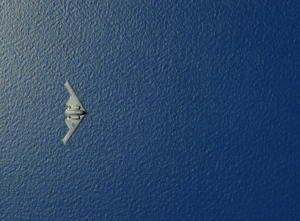

A B-2 traverses the western Pacific during a strategic presence mission. Long-range airpower is a key component of AirSea Battle. (USAF photo by SrA Christopher Bush) |

At its core, a finalized AirSea Battle concept will protect America’s ability to project power and secure areas of the “global commons”—the sea and air lanes vital to the nation’s

interests—while relying heavily on air and sea superiority.

“Over the last several decades, the US military has developed and maintained an unrivaled ability to establish and maintain air superiority and sea control,” said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Norton A. Schwartz in an address at the National Defense University in December 2010. The US has been so successful in projecting expeditionary power, both from long distances and from forward bases, that its ability to do so has been largely unchallenged, Schwartz added.

Marry Up

Today, this is no longer the case, senior USAF, Navy, and DOD officials contend. Potential adversaries, such as China, have made broad investments in technology specifically designed to challenge US access in areas such as the western Pacific. New tools such as advanced fighter aircraft, ballistic missiles, a growing blue water Navy, and advanced space capabilities are all designed to thwart traditional American military advantages.

The expansion and proliferation of anti-access, area-denial (A2/AD) technology, and the strategies these tools support, force some serious thinking about how the US invests in its national defense, Schwartz contended. “We face a reality requiring more disciplined spending, efficiency, innovation, and interservice integration and interoperability,” he said. AirSea Battle is the first step in facing these concerns, and eventually the idea must be “inculcated” into the military’s joint culture. This will be done by addressing institutional changes in service culture. The goal is to normalize collaboration, reach a conceptual agreement on how air and sea forces integrate and operate together, and seek compatible systems.

AirSea Battle emerged from a memorandum between the air and sea services in 2009. The Air Force and Navy realized sophisticated threats involving high technology, networked air defenses, modern ballistic missile, and sea and air capabilities, and anti-space weapons required the services to marry up many of their respective strengths. The plan, which has received a great amount of attention since the 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, mandated the creation of an operations concept to protect US and allied access to certain areas in the world while also protecting forward-based assets and bases. This type of operating environment would be drastically different from the largely permissive one seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, and necessitates overcoming anti-access and area-denial capabilities.

|

USAF Capt. Cole Davenport performs a preflight check on a Navy EA-18G Growler. Davenport is the first Air Force electronic warfare officer to graduate from Growler training. (USAF photo by SSgt. Gina Chiaverotti-Paige) |

Both services are said to be fully on board with the plan, and to weed out duplication, officers from each branch have been cleared to see “all the black programs,” or classified projects, of the other service as the ASB plan has matured.

Adm. Michael G. Mullen, outgoing Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, cited the ASB effort as an example of a new approach to an emerging threat environment, made all the more important because of the new budgeting realities the military will face in the coming years.

“No one can do it alone,” he said during the disestablishment ceremony for US Joint Forces Command in Suffolk, Va., Aug. 4. “And quite frankly, no one can afford to do it alone, either,” Mullen said. AirSea Battle has led the Air Force and Navy to set aside parochial interests to overcome a serious 21st century threat scenario. “This and many other joint approaches would have been almost unthinkable a mere generation ago,” he said.

The plan had been vetted by both services by June, and is awaiting blessing from the Office of the Secretary of Defense (see box). Service officials have been predicting a formal release of more information on the doctrine for months as well.

As early as Feb. 17, Lt. Gen. Herbert J. Carlisle, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for operations, plans, and requirements, had said a public document explaining the outlines of ASB in detail would occur “possibly within two weeks.” The now-retired Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Gary Roughead told reporters in Washington in March he expected to release details on ASB in “a few weeks,” as the service Chiefs of the Marines Corps, USAF, and Navy were “basically done” with their work on the concept. The majority of the plan will remain classified, he added, “as it should be.”

|

|

Fiscal Constraints

As time has dragged on, and the fiscal picture darkens, budget considerations have increasingly colored public discussion of AirSea Battle (and the frequency of the public pronouncements on the topic have dropped off as well).

The Air Force is facing a situation similar to the post-Cold War budget drawdown of the early 1990s, said Air Force Vice Chief of Staff Gen. Philip M. Breedlove during a July 20 speech in Arlington, Va. Then, the service had just emerged from a strong period of Reagan-buildup weapons modernization. Today, the military is coming out of a decade of war and operating aged platforms.

“We’re in a tough spot,” Breedlove said. “We see near-peers or peer competitors beginning to build similar capabilities [to USAF] in stealth, … long-range strike, [and] missile technology. … These countries have money and they have a very deliberate plan which they are good at executing, and they will bring pressure to our advantages across the world, all at the same time.”

|

A Navy landing signalman guides an Air Force HH-60G Pave Hawk as it takes off from the deck of USS Ponce during operations off the coast of Libya. (USN photo by Mass Comm. Spc. 1st Class Nathanael Miller) |

The long-term fiscal constraints faced by USAF will challenge the service’s ability to remain ahead of the technology curve. In some cases, the Air Force will not be able to “buy its way through” its difficulties, Breedlove said.

Funding profiles in DOD’s research and development accounts—a key indicator in developing new USAF and naval platforms to meet requirements—are already showing the strain. According to a July analysis of the Pentagon’s 2012 budget proposal by the Washington-based Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, the budget is shifting research, development, test and evaluation dollars away from early research activities into pursuits that develop and demonstrate more mature capabilities. As a share of

the RDT&E budget, early research has fallen from 21 percent in Fiscal 2001 to 16 percent in 2012. Overall RDT&E funds are slated to further decline to $65 billion in 2016, down from a peak of $83 billion in 2009.

Despite the lack of information, there is some evidence USAF and the Navy are already coordinating their exercise and experimentation plans to match up with ASB concepts. The Air Force’s Joint Expeditionary Force Experiment franchise, a series of live, virtual, and constructed experiments run by the Air Force Command and Control Integration Center, plans on focusing on AirSea Battle concepts with the Navy in Fiscal 2012.

The Marine Corps is also planning on beefing up exercising for amphibious operations in the near future. Lt. Gen. Dennis J. Hejlik, commander of Marine Corps Forces Command in Norfolk, Va., told reporters in Washington in June the Navy and USMC plan to conduct exercise Bold Alligator 2012 early next year to build and exercise fundamentals of amphibious operations. This will be one of the first opportunities for marines to familiarize themselves with concepts laid out in ASB, he said.

“We will do some of the experimentation there and see if we can take that concept … and practicalize [it],” Hejlik said, noting the Marine Corps didn’t get fully involved in the process of building the plan until January 2011. “What we’re really looking at … is the assured access part, and that’s a big part of AirSea [Battle],” he said, adding that it will take time to incorporate new concepts into Marine Corps operations.

Growing budget worries, and the impact on force structure to carry out future training and cooperation activities, are leaving many questions about future capabilities. The Air Force’s budget troubles, and hiccups in the development and fielding of both the F-22 and F-35, have forced the service to adjust force structure plans—particularly in its fighter fleet. As such, there are implications for how much combat power could be brought to bear in any near-term A2/AD fight, USAF officials contend.

|

Sailors tour a B-2 stealth bomber at Andersen AFB, Guam. USAF and the Navy are already coordinating exercises to follow ASB concepts. (USN photo by Oyaol Ngirairikl) |

Core USAF Contributions

“The high end fight has a necessity to it, and there is a ‘contested’ environment that has a necessity to it,” said Col. Timothy Forsythe, the chief of the combat aircraft division at Air Combat Command’s requirements shop, in a June interview. Differences between a permissive, a contested, and an A2/AD fight are driving some careful decisions for ACC, Forsythe noted, as there is about a 300-airframe fighter gap between its planned force structure and requirements now on the books. These requirements are sure to change as AirSea Battle is refined.

“We are flying these aircraft beyond their service life,” Forsythe said of USAF’s legacy—or “proven,” as he calls them—fleet. The health and future viability of additional F-15s and F-16s are getting a harder look, as USAF considers modifications ranging from structural reinforcements to sensor and radar upgrades to help fighters stay relevant to future conflicts.

While modernization plans are under way, many of the assets in the fleet won’t get USAF where it needs to be vis-a-vis anti-access threats, Forsythe noted. This is what makes the state of the F-35 and F-22 fleet so important to future threat planning.

The Air Force is not alone in budget woes, as concerns about the F-35 and various combat ships could affect naval force structure as well. Development troubles with the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship program have aroused the ire of Congress, with Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) noting in July that the Navy could be the service “most adversely affected” by anticipated budget cuts, due to its handling of LCS. Cuts could also affect the sea service’s plans for modernization of its ballistic missile submarine fleet and future carriers.

But a core Air Force contribution to the AirSea Battle plan is the next generation long-range strike platform—what is now known as the long-range bomber. One of the Pentagon’s critical needs in pursuit of its ASB concept is for credible, enduring, long-range strike capability. A May 2010 study by the CSBA, citing the need for an AirSea Battle plan to counter the deteriorating military balance in the western Pacific, charged that the Pentagon had until then underfunded LRS development.

Some senior Pentagon officials have continued to deride the necessity for such a platform, with the then-vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Marine Corps Gen. James E. Cartwright, saying he was known as a “bomber hater” in a July conversation with reporters in Washington. He questioned the need for a manned bomber in a future force structure and admitted throwing the gauntlet down to get the Air Force to prove a bomber is necessary. The Air Force plans on fielding a fleet of between 80 to 100 of the bombers, and while some requirements are finalized, a program office is not up and running yet—and much of the program remains classified, the Air Force has stated.

|

|

The renewed focus on the mission—the global projection of strategic combat power from the air—comes at a difficult time. Senior leaders admitted this even as the ASB concept was still under assembly last year. Leaders frequently talked of it as a “family of systems” rather than any one program, foreshadowing the impetus behind the marriage of naval and USAF long-range strike capabilities in the ASB plan.

Resources are not keeping up with requirements growth in the long-range strike portfolio, said Lt. Gen. Christopher D. Miller during a November 2010 speech in Shreveport, La. Having spent several years emphasizing the nuclear mission, the Air Force now needed to once again approach LRS from a “mainly conventional perspective.”

ASB Drivers

“Getting the balance right, … so we end up with a competent, fully resourced family of systems, is something my team is focused on,” said Miller, the Air Staff’s head of strategic plans and programs. The “family” concept would marry together Air Force capabilities, across many systems, and airmen will have to think critically about how to put all of these elements together to generate the “maximum effect.” The LRS family must possess enough range and payload to overcome tough anti-access environments.

In July, Carlisle said the new bomber will be able to prosecute tasks from electronic attack to intelligence-surveillance-reconnaissance in addition to performing a wide spectrum of strike missions. “I don’t necessarily think you’re going to make four different airframes,” he said in an interview with Air Force Times. “There is either the ability to plug and play, or the same platform with different capabilities being ISR, EA, or kinetic attack.” The bomber would not be modular exactly, but could carry specific payloads, depending on the profile of the strike mission.

In more recent statements, senior service leaders have stressed affordability of the new bomber, especially since the services scrubbed their budgets before submitting them to OSD this fall. The bomber must be built with “proven technology,” Breedlove said, and development must start today to be fielded when needed (by the early 2020s, by most estimates).

|

|

Still, in July, Breedlove did not mince words about the need for a new penetrating bomber—calling it a service “core capability,” and its development and deployment into the operational force a necessity. The Air Force must maintain the ability to strike targets across the globe from the air, he said in a July 20 speech. He called it a valuable deterrent and a capability the nation depends on in a range of scenarios, from Iraq to Afghanistan to Libya. “We will continue to need its capability into the future,” he said, especially in anti-access and area-denial situations.

The “pacing threat” from China is real, and a real driver for AirSea Battle concept, said Carlisle during AFA’s Air Warfare Symposium. The anti-access, area-denial threat, the vast distances involved in the western Pacific, and unrelenting budget pressures have forced the largest push for USAF and naval integration since the end of the Cold War.

| An ASB Summer

The AirSea Battle rollout was repeatedly delayed over the course of 2011. According to Office of the Secretary of Defense and Air Force officials, new Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta is reviewing the ASB plan—a sort of executive summary of the overall operations concept (which, as of early September, remains classified). However, then-Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan W. Greenert, now the CNO, told the House Armed Services Committee in late July he expected a release of unclassified portions of the plan soon. The AirSea Battle concept was signed by the USAF, Navy, and Marine Corps service Chiefs, and the Air Force and Navy Secretaries on June 2 and “forwarded to the [Secretary of Defense] for approval,” the Air Force said in a brief official statement Aug. 2. Previous Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates, who departed July 1, had the document in his possession and had told senior Air Force officials he would sign it before his departure. In late July, however, Air Force and DOD officials privately indicated the concept was held up in OSD’s policy shop, and Gates did not sign the document before leaving the Pentagon. Air Force and defense officials have indicated both publicly and privately that there are strong international political considerations at play. Spin “concern” has likely contributed to the delay in officially rolling out the AirSea Battle concept. In late July, USAF officials privately indicated that there is a great deal of concern within OSD about how China will perceive and react to the concept. On Aug. 24, OSD released its annual “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China” report, which promptly drew a rebuke from the Chinese Defense Ministry. It derided the document for “groundless suspicion.” Senior officials frequently couch their comments about AirSea Battle’s main aim—to blunt the Chinese military’s increased capabilities in the Pacific—by noting other scenarios where ASB could be employed. These include potential threats such as Iranian action in the Strait of Hormuz and a variety of scenarios involving a war with North Korea. “When you talk about AirSea Battle, it’s not all China. It really is about the anti-access capabilities that tend to proliferate in many areas” and making sure the US military can operate in those areas, said Adm. Gary Roughead, then Chief of Naval Operations. |