Had it not been for ball bearings, Schweinfurt might have remained a small town in Bavaria and escaped the notice of history. However, it was there in 1883 that a local mechanic, Friedrich Fischer, invented the machine that made possible mass production of ball bearings. In 1906, his son founded the Kugelfischer firm, which became the cornerstone of the industry.

World War II created a huge demand for ball bearings. The German aviation industry alone used 2.4 million of them a month. Production was concentrated in Schweinfurt, where five plants turned out nearly two-thirds of Germany’s ball bearings and roller bearings. Between 1922 and 1943, the surge in manufacturing tripled the population of Schweinfurt to 50,000.

|

B-17s drop their bombs on Schweinfurt, Germany, on Aug. 17.

|

In the summer of 1943, US and British planners for the Combined Bomber Offensive identified the ball bearings industry as a key “bottleneck” target, the destruction of which could clog up war production and potentially shorten the war. The British Air Ministry since 1943 had been trying to persuade the Royal Air Force to bomb Schwein-furt, but Air Marshal Arthur T. “Bomber” Harris, chief of RAF Bomber Command, was adamantly opposed.

The RAF determined early in the war that it could not precisely hit individual targets and took heavy losses in trying. It switched in 1942 to area bombing at night, targeting German cities in support of a national policy of “dehousing” German citizens and workers. Harris dismissed ball bearings and other bottleneck objectives as “panacea targets.” He claimed that RAF bombers would not be able to find a town the size of Schweinfurt at night, much less bomb the factories. His objections were more a reflection of what Harris did not want to do than of actual RAF capabilities and limitations.

On the other hand, Schweinfurt was exactly the sort of target the US Eighth Air Force was eager to strike to demonstrate the value of daylight precision bombing, to which the Army Air Forces was deeply committed. The British wanted the United States to blend its bomber forces into the RAF’s night area bombing campaign. To their vexation, “the Americans were determined to fight in an American way and, as far as possible, under American command,” sniffed British historian Noble Frankland.

Without Excessive Losses

Eighth Air Force B-17s had been flying from England since September 1942, but seldom on large missions or with anything better than mediocre results. Maj. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, commanding Eighth Air Force, had been unable to mount big raids. Many of his aircraft and aircrews were diverted to operations in North Africa and more than half of his remaining resources were assigned to attacking German submarine pens—a high priority for the British—even though bombing had little effect on these hardened facilities.

Eaker was under considerable pressure to deliver a strategic success. In August 1943, he was at last able to put together enough B-17s for a large mission that would launch almost 400 bombers in a deep double strike against the ball bearings at Schweinfurt and the Messerschmitt factories at Regensburg.

The mission, postponed once for bad weather, was reset for Aug. 17. The strike force was divided into two parts. The Third Air Division, led by Col. Curtis E. LeMay, would take off first and bomb Regensburg, 430 miles inside occupied Europe.

The First Air Division, led by Brig. Gen. Robert B. Williams, would take off nine minutes later for Schweinfurt. Williams had the larger force, 230 B-17s compared to 146 for LeMay.

|

As explosives hit the facilities at Schweinfurt, bombs from a higher-flying B-17 plummet past the photographer.

|

Both divisions would follow the same route for most of the way, but beyond Frankfurt, the First Division would swing off toward Schweinfurt. The plan was for both divisions to reach their targets about the same time, the nine-minute interval between them offset by the location of Schweinfurt, which was 75 miles closer than Regensburg. The first bombs were to fall on Schweinfurt at 10:12 a.m., and on Regensburg one minute later.

Although the Messerschmitt plant was important—producing up to 400 Me 109 fighters a month—it was not the main target. By going first, LeMay’s division was supposed to lure away the German fighters to give Williams a better shot at Schweinfurt.

Williams would face the brunt of the German fighters on the return trip, while LeMay’s B-17s, carrying extra fuel in “Tokyo tanks,” continued southward over the Alps and the Mediterranean to land at bases in Algeria. US and British medium bombers would provide additional diversion by attacking targets along the Channel coast about the same time the B-17s were taking off.

Never before had B-17s ventured so deep into Germany, and they would be without fighter escort for most of the way. British Spitfires could go with them only as far as Antwerp in Belgium. American P-47 Thunderbolts would have to turn back at Eupen, about 10 miles short of the German border.

In the 1930s, the Army Air Corps had concluded that well-armed bombers could protect themselves. Development of a long-range fighter lagged. The P-51 Mustang, which could go all the way with the bombers to the most distant targets, would not be available until December 1943.

In October 1942, Eaker still held that “the B-17 with its 12 .50-caliber guns can cope with the German day fighter, if flown in close formation” and that “a large force of day bombers can operate without fighter cover against material objectives anywhere in Germany, without excessive losses.”

Most of the bombers on the Regensburg-Schweinfurt mission were B-17Fs. Their guns provided overlapping cones of fire from the waist and from the top, belly, and tail turrets, but the B-17F did not have the nose turret that came on the B-17G. Handheld guns firing to the sides from “cheek” blisters did not close the gap.

|

Fires spread through the target city during the Oct. 14 raid.

|

“We definitely lack firepower in the nose of the B-17,” LeMay said. The Luftwaffe knew this and exploited the advantage of the head-on, 12 o’clock attacks.

All of this was offset, according to the briefings, by the concentration of German interceptors in a “fighter belt” near the coast. The best fighters, single-engine Me 109s and Focke-Wulf 190s, were supposed to be there. Inland, the bombers should expect only slower and less-maneuverable twin-engine fighters like the Me 110, which was built for night operations. Eighth Air Force was unaware that the Luftwaffe had recently switched to a strategy of defense in depth and had brought back Me 109s and FW 190s from the Russian front to protect Southern Germany.

On the morning of Aug. 17, a thick fog covered East Anglia, where the B-17 bases were. LeMay’s division had been scheduled to launch at 5:45 a.m. At the insistence of VIII Bomber Command, takeoff was delayed for an hour, then for an additional half-hour. Further delay would mean running out of daylight before reaching the landing bases in Africa. Fortunately, LeMay had drilled his crews for a month in bad weather instrument takeoffs and the first bomber was in the air at 7:15 a.m.

The Schweinfurt crews, not proficient in instrument takeoff, were stuck on the ground. They finally launched five hours later than planned, more than four hours—instead of nine minutes—behind LeMay’s division, which was almost to Regensburg before the first Schweinfurt bomber took off.

LeMay flew as copilot in the lead B-17. His division formed up at bombing altitude before leaving England. Seven B-17s aborted and 139 crossed the Dutch coastline at 9:35 a.m. Enemy resistance was relatively light in the fighter belt, but when the fighter escorts turned back at Eupen, the Me 109s and FW 190s swarmed and kept coming, sometimes in packs of 25.

Lt. Col. Beirne Lay Jr., copilot on a B-17 named Picadilly Lily, drew on the experience to depict the harrowing losses of the big mission in the book and movie, Twelve O’Clock High, which he wrote with Sy Bartlett. “Near the IP [the initial point for the bomb run] one hour-and-a-half after the first of at least 200 individual fighter attacks, the pressure eased off, although hostiles were nearby,” Lay said in a December 1943 article for Air Force Magazine.

|

Some B-17s aborted before reaching the continent. The 60 B-24s had trouble making rendezvous with the strike force and were diverted to other targets. |

The relentless fighter attacks were difficult to bear, especially for those aircrew members who could not shoot back, said Hayward S. Hansell Jr., who in 1943 was a brigadier general and chief planner for Eighth Air Force. Gunners could relieve some of the pressure by firing back, but that “was entirely lacking to the pilots and bombardiers and navigators,” Hansell said. “They had somehow to rise above the personal danger surrounding them and place the accomplishment of the mission above personal survival.”

Speer Gets Nervous

The bombs began falling on Regensburg at 11:43 a.m., and they clobbered the target. They got not only the main factory buildings but also wiped out 37 Me 109s just off the assembly line. In addition, they destroyed most of the jigs for the secret Me 262 jet fighter then in development. Lost production amounted to 800 to 1,000 Me 109s before full output was restored several months later. The B-17s turned south and, after an average of 11 hours in the air, landed at their bases in North Africa.

The medium bombers made their diversionary attacks along the Channel coast at midmorning, too late to help LeMay and too early to be of much benefit to Williams.

Because of the five-hour fog delay, Williams and the First Division made a change that would have repercussions later. The original plan was for them to fly past Schweinfurt, turn, and attack from the east. This added 17 minutes to their approach, but it allowed them to make their bomb run at midmorning with the sun at their backs. However, because of the long delay, they would arrive at Schwein-furt in the afternoon rather than in the morning. The sun would be more to the west than to the east. If they stuck to the plan, they would spend 17 dangerous and unnecessary minutes in the target area and they would be attacking into the sun. Consequently, they switched directions to make the bomb run from west-to-east rather than east-to-west.

The first of the Schweinfurt B-17s took off at 11:20 a.m. and a procession of 222 aircraft crossed the coast of the continent. The German fighters were refueled, rearmed, and waiting. Williams lost only one bomber in the fighter belt, but the Luftwaffe shot down 23 between Eupen and Schweinfurt, and several more over the target.

Williams himself took over a machine gun in a cheek blister and fired it until the barrel burned out.

|

|

The strike force reached Schweinfurt at 2:59 p.m. Bombing accuracy was not as good as hoped for. Among other complications, the leading groups reached the initial point a few minutes late and the following groups were close on their heels.

Some of the crews were confused by the change in direction of approach to the target. The first three groups had clear bomb runs but the other six had problems and many of their bombs fell wide.

The division then had to fly back through the German defenses on the return trip, and was under sustained fighter attack for much of the way.

The strike on Schweinfurt is often characterized as unsuccessful. Most of the heavy equipment at the factories survived, and the damage done was temporary. Part of the problem, according to Hansell, was that less than a third of the bombs dropped were 1,000 pounders. The others were lighter and had limited effect on the targets. But even so, and despite the operational fumbles, the raid dealt Schweinfurt a hard blow.

The German armaments minister, Albert Speer, said in his memoirs that the bombing caused a 38 percent drop in ball bearing production. Speer could not relocate the industry immediately because he could not afford to stop production during the move. Output was so sparse that plants using ball bearings sent men with knapsacks to pick up as many bearings as were available each day. Stocks were sufficient to cover only six to eight weeks. After the raid, Speer said, “we anxiously asked ourselves how soon the enemy would realize that he could paralyze the production of thousands of armament plants merely by destroying five or six relatively small targets.”

Eighth Air Force had limited means of assessing the strike and had no real idea of how effective the bombing had been. In any case, Eaker did not have enough bombers to mount another mission right away. Official statements put an optimistic face on the raid but the War Department was alarmed by the casualties.

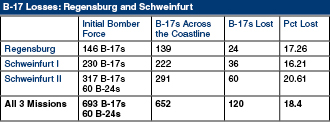

For the day, LeMay’s losses had been 24 aircraft, and Williams lost 36. Many others were so damaged they would never fly again. Of the 601 crewmen lost, 102 were killed. Most—381 of them—were taken prisoner, while others evaded capture, were interned, or were rescued from the sea.

B-17 gunners claimed to have shot down 288 German airplanes and the fighter escorts claimed another 19. In actuality, the Luftwaffe lost between 25 and 35 fighters.

“We destroyed a mere fraction of the German planes claimed and awarded,” LeMay said.

Intelligence reported that the Germans were rebuilding furiously at Schweinfurt and scrambling to obtain ball bearings from other sources, including Sweden. Eighth Air Force would be going back to Schweinfurt. LeMay, without doubt the best combat commander in Eighth Air Force, had been promoted and moved up. He would not be along this time.

On the day of the mission, Oct. 14, there was again fog in the morning, but it lifted. At 9 a.m., a British Mosquito reconnaissance aircraft flying high over Germany reported that the weather was clear.

The strike force consisted of 317 B-17s in two divisions, commanded by Col. Budd J. Peaslee and Col. Archie J. Old Jr. Sixty B-24s were also assigned, but they had trouble in making rendezvous and were diverted to other targets in the Frisian Islands.

B-17s began taking off shortly after 10 a.m. and 377 bombers were soon in the air over England. However, aborts reduced the number to 291 B-17s before they reached the coastline of the Netherlands. The P-47 escort fighters turned back between Aachen and Duren, just inside the German border. The Luftwaffe attacked in large numbers and from all directions. The official Army Air Forces history described the Luftwaffe fighter attack as “unprecedented in its magnitude” and “in the severity with which it was executed.” The Allies estimated that the Luftwaffe had 800 fighters in Europe. In fact, there were 964, and they were still pressing the bombers as Schweinfurt came into view.

Out front in the leading B-17 was Lt. Col. T. R. Milton, operations officer of the 91st Group. He went on to become a four-star general and a longtime columnist for Air Force Magazine, but this day his thoughts were on whether he would survive. He led the bombers over Schweinfurt at 2:39 p.m.

Accuracy was much better than in August, and the three largest ball bearings factories were hit numerous times. According to Speer, the bombs this time destroyed 67 percent of Schweinfurt’s production capacity.

|

|

America’s “Waterloo”

Unfortunately, the Oct. 14 casualties were the highest yet. Of the 291 B-17s that left England that morning, 60 were shot down for losses of more than 20 percent.

At such a rate, an aircrew member on a heavy bomber would have odds of completing no more than five missions before he would be shot down. He had virtually no chance of finishing his 25-mission combat tour and going home.

That loss rate and level of risk to the aircrews were not acceptable. For the rest of the year, Eighth Air Force struck only targets that were within range of the escort fighters. It did not attack Schweinfurt again until February 1944, when long-range fighters were available.

For its part, RAF Bomber Command did not attack Schweinfurt until after the third raid by Eighth Air Force. By then, the Germans had dispersed the ball bearings industry and it was no longer a good candidate for bottleneck targeting.

Frankland, historian of the RAF Bomber Command, dismissed Schweinfurt as “America’s Waterloo.” Others have emphasized the shortcomings of the operation as well. US historian Alan J. Levine said that “ball bearings as a target system had proven a false trail and the fortunes of Eighth Air Force had reached their nadir.”

One of the most quoted lines from the US Strategic Bombing Survey said that “there is no evidence that the attacks on the ball bearing industry had any measurable effect on essential war production.” Less noticed was the judgment of the Survey that the outcome might have been different had Eighth Air Force been able to follow up on the 1943 attacks.

“The Allies threw away success when it was already in their hands, “ Speer said. “As it was, not a tank, plane, or other piece of weaponry failed to be produced because of lack of ball bearings.” In Speer’s opinion, “The war could largely have been decided in 1943 if instead of vast but pointless area bombing the planes had concentrated on the centers of armaments production.”

Schweinfurt did not discredit either daylight precision bombing or the bottleneck targeting strategy. In regard to those issues, the evidence was more positive than negative. Despite some operational errors, the strikes—just two of them—had a dramatic effect on ball bearing production, and had the effort been sustained would have devastated the German industrial base.

What the Schweinfurt experience did disprove was the notion that bomber formations could defend themselves when confronted by a force like the German air force.

In early 1944, Eighth Air Force changed its strategic emphasis to an all-out effort to destroy the Luftwaffe, and within months, the Luftwaffe was no longer an effective fighting force. The Allies were able to conduct the D-Day invasion in June 1944 without interference from the air. British and American bombers were free to attack at will, and with that, the war entered its final phase.