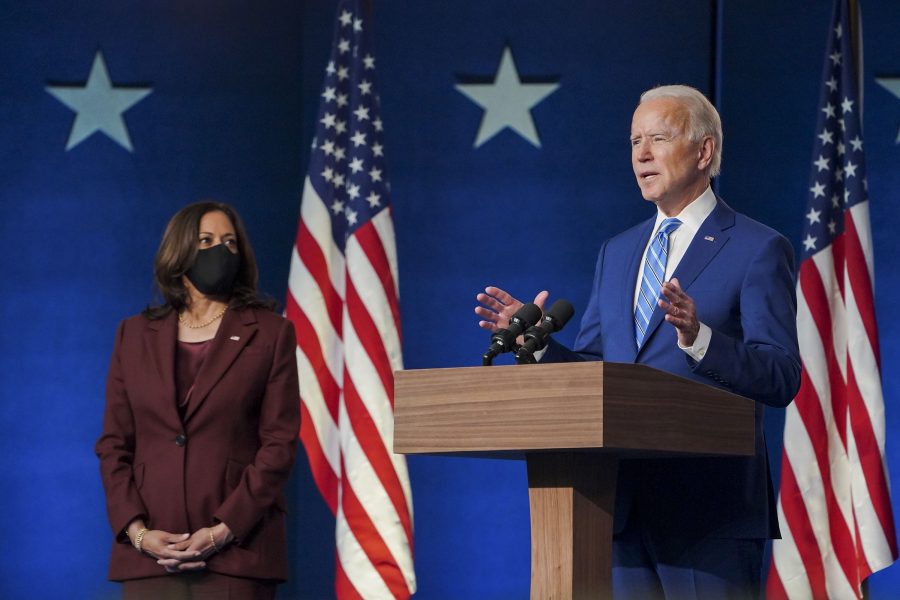

Major news outlets declared former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. the President-elect on Nov. 7, ushering in a new era for the military under a Democratic administration.

Biden has secured enough electoral votes to win the presidency, though Trump has pledged to challenge state results in court based on unsubstantiated allegations of election-official misconduct. His campaign’s past challenges have been dismissed.

Biden’s election as the next commander-in-chief will usher in a middle-of-the-road approach to defense policy that draws on priorities from both the Barack Obama and Trump administrations, observers said.

Budget austerity was slated to plague either potential winner over the next four years. The U.S. defense budget was entering a period of little or no growth even before the coronavirus pandemic began, despite officials pushing for a 3-5 percent bump each year.

It could affect the status quo more than Biden expected, noted Michael E. O’Hanlon, foreign policy research director at the Brookings Institution. Defense and related spending is set to be about $740 billion in 2021.

Conservatives worry a Democratic administration spells trouble for funding that has steadily grown since the 9/11 terror attacks. But budget watchers differ on how aggressively Biden would pursue cuts.

Lawrence Korb, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress, expects Democrats won’t try to take a large bite out of defense spending. Republicans who fear vast underfunding for the military should remember that Obama requested more for the Defense Department in his first budget as President than Trump did in his own first request, he said.

“Even under Trump, they have projected flat budgets for the next couple years,” said Korb, who served as assistant secretary of defense for manpower, reserve affairs, installations, and logistics in the Ronald Reagan administration. “Biden has never been part of the Sanders wing of the party or Warren wing [with big cuts]. I think it’ll be pretty much the same.”

Proposals for large cuts, like Sen. Bernie Sanders’ (I-Vt.) attempt to shrink the Pentagon budget by 10 percent, have failed to garner much support in Congress.

“If the Democrats had won a big victory in the Senate, I think you would have seen the defense budget being cut maybe by 5 percent or something like that,” Korb said.

Republicans will temper any proposals to drastically downsize defense spending, and will try for small increases to the defense budget to keep up with inflation, said Thomas Spoehr, director of the Heritage Foundation’s Center for National Defense.

The election results are likewise unlikely to spur significant changes to either the 2021 defense spending or policy bills, which Capitol Hill has yet to finalize, or the Pentagon’s fiscal 2022 budget request due out early next year, experts said. A Democratic executive branch could still ditch low-yield nuclear warheads and plans for a sea-launched nuclear cruise missile in the 2022 submission, among other programs unpopular on the left.

As chairman of the Democratic-led House Armed Services Committee, Washington state Rep. Adam Smith will be an ally to the White House on defense and a mediator between Biden and congressional progressives. He believes the defense budget could hover around $720 billion to $740 billion in the coming years. He argues that a spending overhaul must be justified by a revamped national security policy, and is optimistic that redirecting some money away from the nuclear enterprise could pay for other wish list items.

Analysts anticipate DOD will put the funds it does receive toward a similar slate of priorities.

The Trump years brought a renewed focus on competition with Russia and China as part of the 2018 National Defense Strategy. While Smith recently called the blueprint “a recipe for a very dangerous and unnecessary Cold War,” experts believe a Biden plan would look quite familiar.

“The National Defense Strategy is pretty much where we ought to be,” Korb said. “The big thing is, and we’ve gone through this so many times, ‘Oh, we’re going to stop worrying about these small wars … you can’t do that.”

China and Russia should remain at the center of an updated strategy as the greatest military threats to the United States, analysts said. “It probably won’t call it ‘great power competition.’ But it will be essentially the same thing by another name,” said Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The main tenets of the National Defense Strategy—increased lethality, better alliances, and reform—will stay the same, Spoehr added.

Biden’s Pentagon will continue pursuing cutting-edge technologies such as maneuverable hypersonic weapons and autonomous combat vehicles, experts said. The department is likely to be more vocal on climate change as a national security threat, support increased humanitarian aid, and allow transgender Americans to serve in the armed forces. Democrats would also delay or avoid arms sales to countries with spotty human rights records.

In carrying out those policies, Biden’s Pentagon may be led by America’s first female Defense Secretary. Former Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy has long been seen as a top pick for a Democratic administration. Other names that have been floated include outgoing Arizona Republican Sen. Martha McSally, the first female Air Force pilot to fly in combat, and Army combat veteran Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.).

Defense policy watchers on the left have urged the next administration to extract the U.S. from myriad conflicts in the Middle East and Africa and bolster diplomacy to resolve them. The President-elect wants to bring thousands of U.S. combat troops home from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan but leave up to 2,000 personnel on the ground there for special operations.

One tough strategic choice Biden could make to create more wiggle room in the defense budget might be to pare back military presence, O’Hanlon said. For instance, DOD could reduce its rotating forces in Europe, as fighting Russia in the Baltics was a bigger concern five years ago than it is now, O’Hanlon said. Permanently basing troops in places like Poland would require fewer people than a rotating force of multiple Army brigades, he added.

He also suggested pulling back from Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia—countries where America’s military presence provides a staging ground for operations in the Middle East.

Gordon Adams, who served as the senior White House budget official on national security in Bill Clinton’s administration, believes Biden’s priorities will heavily depend on which party controls the Senate.

As of Nov. 7, the Associated Press had not declared a winner in Senate races in North Carolina, Georgia, and Alaska. During a Nov. 5 press call hosted by Count Every Hero, a “cross-partisan” effort dedicated to making sure all U.S. troops’ ballots that have been submitted properly and on-time are counted before the results of the 2020 election results are officially called, former Air Force Secretary and initiative co-chair Deborah Lee James urged the nation to give those votes a chance to be counted.

“If you look at the different rules of the states … Nov. 12 is when the final tallies will occur and the final of those battleground states,” she said. “One week of patience is all we need to show to let the process play out.”

She noted that mail-in voting has historically ensured that troops stationed away from the areas where they’re registered to vote—and especially those deployed to combat zones—get a say in such elections.

“Ninety-nine percent of Americans have never served and do not serve in the Armed Forces,” she said. “One percent does serve or has served. So, it strikes me that the 99 percent of us owe it to the one percent … to let their voices be heard and do not let these ballots be thrown out.”

Elections for the two Georgia Senate seats are headed to runoffs in January. The upper chamber is tied 48-48 with four races still undecided.

If Democrats get the upper hand, either through an outright Senate majority or because Vice President-elect Kamala Harris would cast the tiebreaker vote in a 50-50 split, the White House would focus on health care, climate change, and jobs, he said.

Negotiating with a GOP-led Senate would look much like the past several years, Adams said: “Little likelihood of deep cuts in defense, despite progressive caucus efforts. Not much growth, perhaps less than inflation.” New technologies and naval forces would be the priority then, he argued, pulling funds from areas like nuclear weapons programs and Army manpower.

“For the Air Force, I would expect trims in the F-35 buy in the outyears, slower bomber progress, [intercontinental ballistic missile] cuts,” he said. It’s also possible Democrats could try to scale back ambitious plans for the Space Force, such as growing it into a separate department like the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

Harrison cautioned against pulling back investment in military space as a “knee-jerk reaction” to undo the Trump administration’s work. He expects the Space Force is here to stay, but that other pieces of the military space enterprise could face more scrutiny.

“Things like the Space Development Agency, that might not have the same support under a Biden administration,” he said. “They may try to fold it into the Space Force sooner, and they may not be enamored with some of the missions that the SDA is attempting to take on, particularly the missile sensing layer. Those programs could be at risk.”

If a Republican Senate has to cut deals with a Democratic House and President, GOP lawmakers could use Democratic priorities as leverage to keep divisive nuclear weapons programs, according to Spoehr. He argues the GOP won’t trade off sea capabilities, and will try to keep F-35 procurement from slowing down.

“They’d be willing to compromise, I think, on some of these areas of force posture, like forces in Germany, Korea,” Spoehr added. “There’s many Republicans who don’t think we ought to vacate some of these places where we’ve been talking about.”

Slim majorities in both chambers of Congress can moderate spending levels and force more bipartisan efforts to compromise on contentious issues, analysts predict. Republicans have retaken some of the advantage Democrats won in the House in 2018, and the blue senators who won in red states won’t be “raving liberals,” Korb said.

“Most defense issues don’t break down neatly along partisan lines,” Harrison added.

Nuclear weapons will remain a major sticking point between the two parties during Biden’s term. At a minimum, the administration is expected to push back on the “low-yield” W76-2 nuclear warhead for submarine-launched missiles, plus a new sea-launched cruise missile. Some believe the land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles and the air-launched cruise missiles could be in jeopardy.

Korb said ICBMs are likely here to stay because of their bipartisan support from members of Congress whose states are home to the missile fields. If the Democratic national security establishment wanted to change course on ICBMs, they would have done it during the Obama years, Harrison noted.

“They studied it and they considered it and they did not [change course]. They had every chance,” Harrison said of the Obama administration.

A new Nuclear Posture Review could leave open the possibility of deploying fewer than 400 ICBMs, the current number, across the northern U.S. in the 2030s.

“In all likelihood, they wouldn’t want to reduce the number of missiles unless we’ve got an agreement with Russia and/or China, or bilateral or trilateral reduction,” Harrison added.

Analysts anticipate Biden will put his own stamp on arms control by reversing the Trump administration’s decision to leave major international treaties.

Korb said Biden would try to extend and renew the New START arms control agreement with Russia that limits how many nuclear warheads and delivery platforms like bomber planes can be deployed at once. Trump’s administration may also reach a deal to extend the pact during his last months in office, setting up the Biden White House to craft a new treaty.

Biden is also expected to revive the Iran nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), under which Iran dismantled much of its nuclear program before the U.S. withdrew in 2018. The administration may rejoin the Open Skies Treaty, which allows a global coalition of nations to inspect each other’s military installations from the air. It can also pursue new terms to govern the use of intermediate-range nuclear weapons, after the U.S. withdrew from that pact in 2019.

Those issues make some feel like they’re replaying Biden’s eight years as Obama’s veep.

“More like an Obama third term, … that’s probably the best way to think of it,” Harrison said.

Digital Editor Jennifer-Leigh Oprihory contributed to this report.