The Department of the Air Force’s top officers are beginning to lay the groundwork for changes to how they manage and provide air and space forces to commanders around the world.

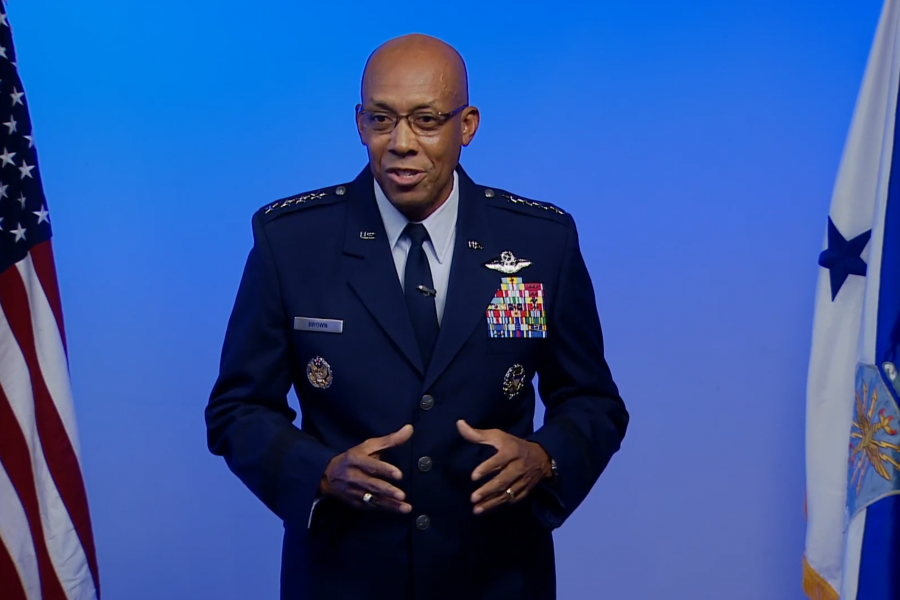

In his first month as Air Force Chief of Staff, Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. has warned that the service needs to overhaul its inventory and quicken the pace of warfare, or risk falling behind other global powers.

To get after that goal, the service’s operations policy team is thinking of new ways to bring in, train, and employ Airmen for global operations, Brown said. Their findings may affect the fiscal 2022 budget request, which is due early next year, and could soon shape deployments overseas.

“Under the leadership of [Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations Lt. Gen. Joseph T. Guastella Jr.], we’re going to conclude that sprint, sit down with Gus on Friday, and say, when are we going to get this thing done so we can go ahead and deliver?” Brown said Sept. 14 during AFA’s virtual Air, Space & Cyber Conference. “My goal is to get this done by the end of the year. We want to make our force generation and force presentation model easy for us to understand and to articulate inside our Air Force, [and] easy to understand in our joint force.”

The plan could debut around the same time as the Joint Staff’s fresh take on joint warfighting, due out in December. Some new ideas will roll out at this fall’s Corona meeting of the service’s top generals, Brown added.

The Air Force is also considering a shakeup of its Air Staff to update how it handles policy areas from manpower to nuclear operations. Those changes could mirror how Air Combat Command has streamlined its intelligence and cyber forces as well as its various fighter, attack, search-and-rescue, and other aircraft.

Proponents say combining pieces of the Air Force make Airmen consider how various fields connect and how they could affect or bolster each other in combat. Brown has foreshadowed hard decisions ahead to cut certain aircraft and other parts of the force. He wants to focus on what’s most valuable for fights against digitally savvy, advanced militaries like Russia and China, like smarter sustainment, technology-driven training, and evolutions in unmanned aircraft, artificial intelligence, and networking.

“It’s better to have a force of quality than a force of quantity that is missing parts like manpower, sensors, command and control, weapon systems, and sustainment,” he said.

Brown stressed that internal Air Force reorganizations should complement work underway on the Joint Staff and in the other services to best reflect the roles and missions of each.

“We do have some overlap. Some of that’s good, but some of it may be redundant. We need to eliminate some of those redundancies,” he said. “It may drive some levels of reorganization, and if we do reorg, form must follow function. Any efficiency we gain, we need to turn into an opportunity to repurpose manpower, so we can put that manpower against emerging missions or underresourced missions.”

At the same time, the Air Staff can also learn from how the Space Force is standing up its own policy shop for the first time. Lt. Gen. B. Chance Saltzman, the Space Force’s operations boss, told Air Force Magazine on Sept. 11 that he is avoiding the traditionally separate offices used for operations, cyber, and nuclear policy.

Instead, he wants to split staffers into three areas: those who track current operations and geopolitical conditions, those who analyze that data to see how it affects the force, and those who plan for the future.

It’s a more holistic approach to combat planning than the military usually employs, and Saltzman hopes it will make the Space Force faster and smarter.

“The ‘what’ bin, they’re the ones that are collecting all the information. What’s going on in the world? What are the conditions that are affecting us? What’s the environment look like? What missions are going on? What are the people doing? What’s the adversary doing? … So we have situational awareness about all of the activities that affect the Space Force and its mission,” Saltzman said.

“The ‘so what’ is making meaning out of that. What are the impacts? If the Russians are conducting this exercise, what does it mean for the Space Force? What does it mean for the joint force? If there’s an environmental condition, whether it’s a hurricane or whether it’s space weather that’s affecting us, how is it affecting us?” he continued.

The “what next” team comes up with courses of action and force management ideas to improve the service’s training, resources, and organization.

“I’m not looking at the badges they’re wearing or what job they had before they came to the staff,” Saltzman said. “I’m taking all of that expertise and dividing them along those three lines.”

He added that Space Force deployments won’t change much in the short term. Most space missions, from satellite operations to rocket launches, are handled from control centers on domestic soil.

Airmen with the 16th Expeditionary Space Control Flight and the 609th Air Operations Center at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, became the first deployed service members to join the Space Force on Sept. 1. Those Airmen handle work such as finding and analyzing electromagnetic interference with U.S. satellites that affects operations in the Middle East.

“Right now, with our current capabilities, it’s just one of our mission sets, or just a small handful of our missions that we actually need to go overseas to perform. The vast majority of the capabilities, we can do from our garrison locations,” Saltzman said. “Because the numbers are so small, we don’t have to go through a radical shift in how we deploy. We still leverage the Department of the Air Force capabilities for assigning and determining what are the requirements, and then we deploy people as necessary, if they have to go to a forward location to accomplish their mission.”

That could change as the Space Force matures and gains new abilities over time, he added.