NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — Pentagon and industry officials have discussed dynamic space operations with frequently satellite maneuvers for years. But with China’s advances in space, the urgency for figuring out how to make that possible is growing.

Maj. Gen. Dennis O. Bythewood, special assistant to the Chief of Space Operations, says a detailed analysis of dynamic space operations is now underway.

“We’re kicking off that work to really get past the ‘Hey, this is a good thing’ to specifically, ‘What are we looking at for advantage? How would we architect in order to deliver that advantage? And what are the implications of that on future force structure for the Space Force?’” Bythewood said at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference here Sept. 23.

U.S. Space Command leaders have been clear that they want to maneuver “without regret,” eliminating the fuel conservation constraints that currently minimize such operations in orbit. Expending as little fuel as possible is today the only way to preserve the service life of a satellite.

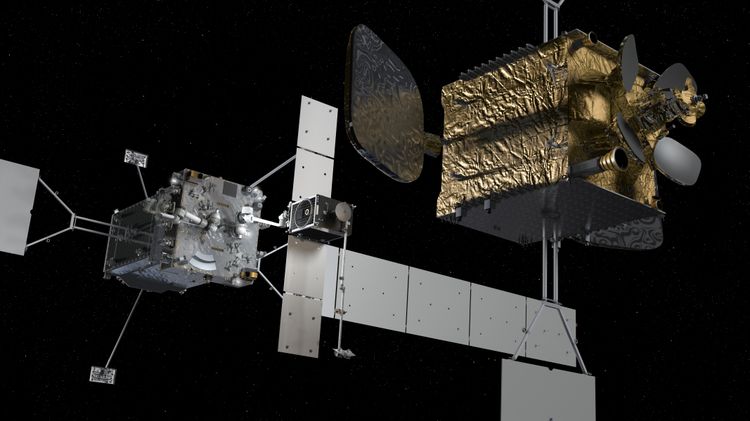

Some companies have developed concepts for refueling satellites or launching spacecraft that latch onto existing satellites essentially act as jetpacks, maneuvering them once their fuel is spent. Rob Hauge, president of Northrop Grumman’s Space Logistics subsidiary, said his firm has not only deployed “Mission Extension Vehicles,” but is already working on a “next-generation servicer.”

China may be ahead here, having invested in satellite refueling. It conducted a refueling operation this summer in geosynchronous orbit, moving fuel from one satellite to another. At another panel discussion at the conference, Chief Master Sgt. Ron Lerch, senior enlisted advisor to the Space Force’s top intelligence officer, called that work a “game-changer” for China, which does not have the same launch capacity and capability as the U.S.

Bythewood, for his part, said he wasn’t surprised to see China’s demonstration.

“Our adversaries are moving forward with capability to threaten us in the domain and the ability to protect themselves in that domain,” he said. “What we see here is another step along that way. Movement and maneuver … is inherent to military operations in any domain, so the idea that China would be looking to enhance its ability to conduct movement and maneuver in the domain, it’s expected.”

How exactly the U.S. might counter is less clear. The Space Force has funded refueling demonstrations scheduled for 2026 and 2028, but the service hasn’t committed to more beyond that. Bythewood noted that refueling is only one option; another is simply to replace satellites in orbit more rapidly. SpaceX’s reusable rockets, a technology China has not replicated, has driven down the cost of launch, which might make it less costly to simply replace satellites rather than refuel them.

Hague said not all space maneuvers are equal. “Dynamic space operations” are “like a fighter capability, the ability to maneuver very quickly to defend or engage,” but one could also pursue “reactive space operations,” or the ability for large satellites to “get off their node very quickly, to be reactive to a threat, and then get right back for the mission.”

Bythewood hinted that the Space Force is open to refueling for certain satellites.

“In some cases, the answer is, ‘I’m going to extend a mission that’s largely static or needs a new payload or an upgrade.’ Other missions are inherently driven by maneuver,” he said. “So life extension for a high-maneuvering spacecraft, where a maneuver is core to its job, is refueling.”

The most high-profile maneuvering satellites in the Space Force’s fleet are in the Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program, which consists of “neighborhood watch” birds that travel through GEO examining objects and threats.

GSSAP satellites are not known to be refuelable and the Space Force is starting to think about replacements: USSF hosted its first industry day for the Geosynchronous Reconnaissance & Surveillance Constellation, or RG-XX, in August.

Details remain sparse, but Monty Greer, a senior project leader at the Aerospace Corporation, argued in favor of making a refuelable solution.

“What I would plant the seed for is: How do we make that the first opportunity to have a serviceable geosynchronous space domain awareness platform that relies on being able to maneuver to do its mission?” he asked. “It’s not just life extension. Can we do that as the first instance of a program of record that demonstrates that capability?”

If the Space Force does decide to go that way, it may need to act relatively quickly, Hauge suggested.

“If we really want to embrace [refueling], the time is now to start modernizing our fleet,” he said. “It typically takes three to five years to build a spacecraft. Putting a refueling port on that spacecraft if the first step.”