The Pentagon agency charged with building and operating U.S. spy satellites recently declassified some details about a Cold War-era surveillance program called Jumpseat—a revelation it says sheds light on the importance of satellite imaging technology and how it has advanced in the decades since.

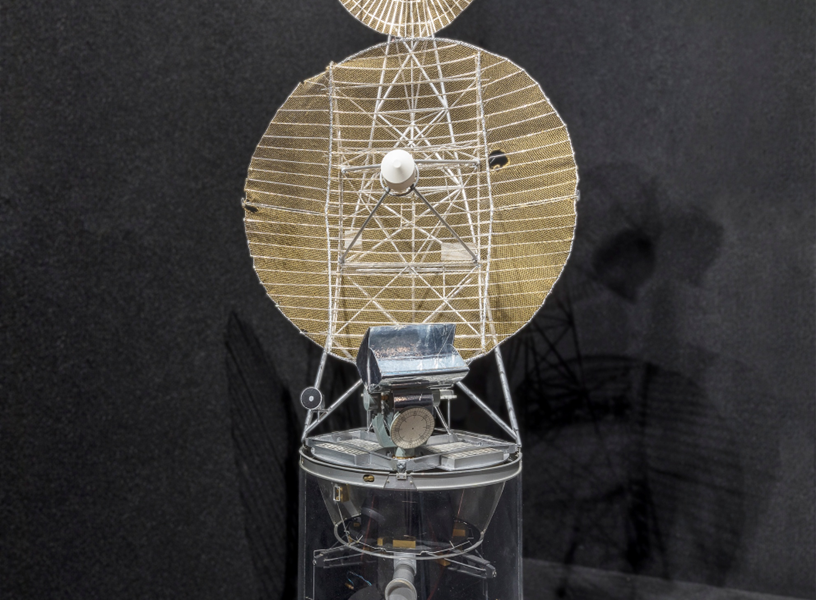

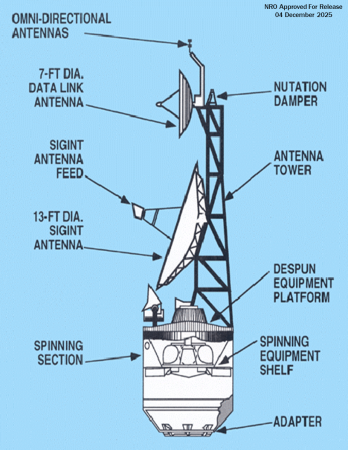

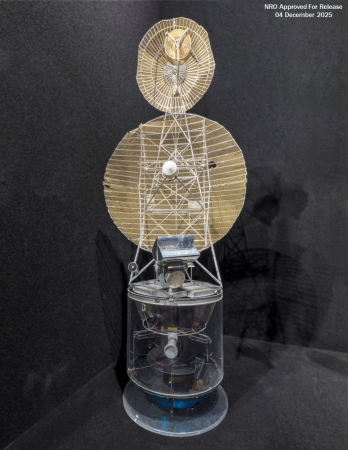

The existence of the National Reconnaissance Office’s Jumpseat program has been in the public domain since the 1980s, but little was known about the constellation until now. In a Jan. 28 news release, the agency disclosed new details about the program’s origins, its mission, and the role the Air Force played in developing and launching it. It also released images and illustrations of early Jumpseat satellite models.

In a declassification memo dated Dec. 5, NRO Director Chris Scolese wrote that shedding more light on the program allows the public to understand the value of Jumpseat and its historic significance. He described the program’s declassification as “limited” and said the agency will consider a more complete reveal “as time and resources permit” and in coordination with the Air Force and the National Security Agency.

“I have concluded that publicly acknowledging limited facts will not cause harm to our current and future satellite systems,” Scolese said. “Additionally, acknowledging the program is consistent with our obligation to the American public to be both open and transparent where possible through declassification of historic programs.”

The satellites, which operated from the 1970s until the early 2000s, intercepted communications and data from the Soviet Union and other U.S. adversaries about systems they were developing, including long-range missiles and atomic weapons.

“Jumpseat’s core mission focus was to monitor adversarial offensive and defensive weapon system development,” NRO said. “From its further orbital position, it aimed to collect data that might offer unique insight into existing and emerging threats.”

NRO and the Air Force codeveloped the satellites under an effort called “Project Earpop.” While the agency had other electronic surveillance satellites operating in low-Earth orbit at the time, Jumpseat was the NRO’s first such spacecraft to operate in highly elliptical orbits, which provide near-continuous coverage of Polar regions.

“The historical significance of Jumpseat cannot be understated,” James Outzen, NRO’s director of the Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance, said in the statement. “Its orbit provided the U.S. a new vantage point for the collection of unique and critical signals intelligence from space.”

NRO launched the first Jumpseat satellite in 1971 from what was then Vandenberg Air Force Base in California—today, it’s a Space Force base—and by 1987 it had eight spacecraft in orbit. The final satellite was decommissioned in 2006.

While Jumpseat was developed as an internal DOD project, today the government relies heavily on unclassified commercial satellites for its Earth observation mission. NRO in recent years has made a concerted push to rely more on commercial systems, and its Commercial Systems Program Office manages contracts with companies like HawkEye 360, Capella Space, ICEYE US, and Umbra, who provide a mix of space-based intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities.

Under its Electro-Optical Commercial Layer program, launched in 2022, NRO plans to spend more than $4 billion on commercial imagery over a 10-year period. Multiple news outlets reported last year that the Trump administration had proposed cuts to EOCL and other commercial imagery programs in its classified fiscal 2026 budget request, but lawmakers moved to restore that funding.

Speaking at a Mitchell Institute event in December, NRO Deputy Director Maj. Gen. Christopher Povak said the agency views commercial ISR providers as a “force multiplier,” allowing its classified systems to perform more military-unique missions and making it easier to share data with allies and partners.

“That integration of commercial and national systems is critical, and I think we see exceeding value in that,” Povak said.