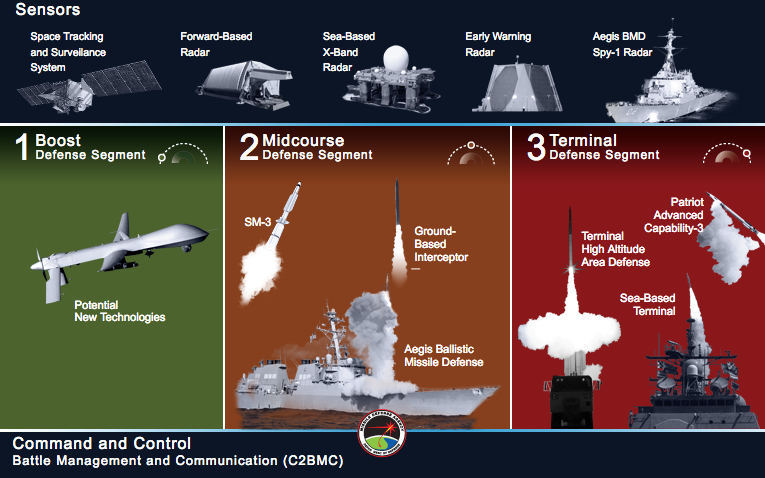

This photo illustration shows the United States ballistic missile defense system. Missile Defense Agency graphic.

North Korea has yet to demonstrate all the technologies proving it has a true means of hitting the US with nuclear weapons, but if it does, the amount of warning time will have shrunk to just “a dozen minutes or so,” Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs USAF Gen. Paul Selva said Tuesday.

Speaking with reporters in Washington, D.C., Selva said Kim Jong Un has not yet demonstrated “all the components” of an ICBM. To have a fully functioning system, a rocket and a warhead are not enough, Selva explained. “You have to be able to maneuver the actual rocket … [and] cause it to do the roll maneuver that actually points it in the direction of the United States,” he said. Also needed is a terminal guidance system that allows the weapon to be targeted and fuzed, and all of this must be inside “a survivable re-entry vehicle that can withstand the stress and shock of both the launch, the transit, and the re-entry. Because all involve heat and vibration.”

The US has not yet seen Kim demonstrate “the fuzing and targeting technologies … or the re-entry vehicle,” he said. However, the US is required to “place the bet that he might have them.”

Selva said he’s unaware of any way a re-entry vehicle could be tested underground, as North Korea has done with much of its nuclear and missile programs. “I believe we would be able to observe the tests,” he said, adding that Kim “hasn’t shot at the distance required,” yet, either.

He cautioned, though, that North Korea hasn’t done any of its ICBM development in “the way we would do it. So it is possible, although I think unlikely, he’s found a way to do the testing another way.”

Selva said North Korea has developed new vehicles, called MELs—Mobile Erectors—that can rapidly raise a missile already prepped for firing. These are unlike TELs—Transporter-Erector-Launchers—that must first elevate a missile, fuel it, and make other preparations before a missile can be launched. The MELs take a missile out to a circular concrete launch pad and the missile is ready to go.

“So we may have gone from tens of minutes,” or as much as an hour, “to a dozen minutes or so” of indications that a missile is being readied for launch, Selva said.

Asked if the US, seeing such a situation, would preemptively attack to prevent a launch, he said “we don’t do preemption.” However, the US would also not simply sit by and wait to be attacked, Selva suggested. Actions would have to be taken in context with “rhetoric” and “provocations” that would signal intent to launch. Deploying all of North Korea’s missiles to launch mode would signal intent, and make whatever missiles the US could see, as well as all the infrastructure that supports them—crews, fueling, command and control, headquarters, etc.—“legitimate, proportional, discriminate military targets.”

Selva said it’s unlikely the US would be able to know where all of North Korea’s missiles are, but by attacking their supporting infrastructure, those not directly destroyed could be rendered useless. “I have confidence we can get at most of his infrastructure,” Selva said of Kim. If “the poor sergeant” whose job is to launch the missile is bombed in his barracks, he’s “not available” to launch the missile, Selva pointed out.

All this would still be challenging, Selva noted, because North Korea is “very disciplined” about concealing its activities when a US spy satellite is going overhead, and every aspect of North Korea’s missile program has been built in facilities that have been skillfully camouflaged, he said.

“It’s very hard to catch them out in the open,” he admitted. Still, the US is “as diligent as we can be” monitoring the North Korean posture.

It’s always possible that an attack might be a “bolt out of the blue” with no contextual warning, Selva acknowledged. But more likely, an attack would be preceded by heightening tensions, to which the US would respond by deploying more forces in the region. “Then we will likely have forces in place to respond to a launch that are different from our day-to-day posture,” he explained, declining to offer further details.

Selva gave a thumbnail sketch of the capabilities in place to detect, launch, and counter an ICBM launched from North Korea. Space-based infrared sensors would detect “the signature of a launch” and “very quickly” characterize the type of rocket from its heat signature, and its point of origin. Ground-based radars would then be able to track the missile and determine if it’s a threat to the US, he said, and if it is, they can also help engage it with missile defenses. Interceptors are based in California and Alaska, positioned to defend against a North Korean attack. He acknowledged there also are other means of surveilling Kim’s missile program, but couldn’t discuss them because they are “pretty sophisticated, and they’re also perishable.”