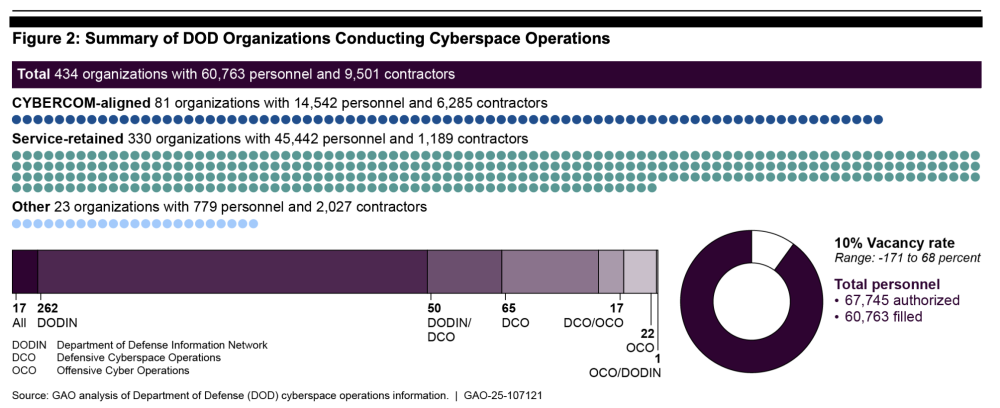

The Department of Defense has about 440 organizations, 61,000 uniformed and civilian personnel, and more than 9,500 contractors working in cyberspace operations, but there may be room to pare down that sprawling $14.5 billion enterprise, the congressional watchdog Government Accountability Office said in a Sept. 17 report.

“Although some overlap can be intentional and appropriate, unnecessary overlap can lead to organizations paying for the same service or product twice or more,” GAO wrote.

Those include foundational training courses and 23 cybersecurity service providers, or CSSPs, that perform similar functions, which GAO said may present an opportunity to consolidate.

The GAO report comes out amid a renewed debate over whether the Defense Department should stand up a cyber force as a separate service branch. Currently, each branch organizes, trains, and equips its own cyberspace units who either work for their respective services, in joint roles, or are presented to U.S. Cyber Command.

Earlier this month, the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, released an implementation plan for building a cyber force which retired Rear Adm. Mark Montgomery, FDD’s senior director on cyber and technology innovation, said could serve as a roadmap for standing up such a service. FDD suggested the cyber force would be a separate service within the Department of the Army, just like how the Space Force exists within the Department of the Air Force.

“There’s a chance that President Trump makes the decision in six to 12 weeks,” Montgomery told reporters, according to Federal News Network. “And if that’s the case, someone needs to have done a blueprint.”

FDD has advocated for a separate cyber force for years, but last month the Center for Strategic and International Studies partnered with FDD to start a commission for analyzing solutions to problems in the current military cyber force, such as a shortage of skilled personnel and inconsistent training.

“The issue remains unresolved precisely because there’s a clear recognition that, as a country, we are not militarily meeting our potential, and the trajectory isn’t ‘good enough,’” commission co-chair Josh Stiefel, a former professional staff member on the House Armed Services Committee, said in a release last week.

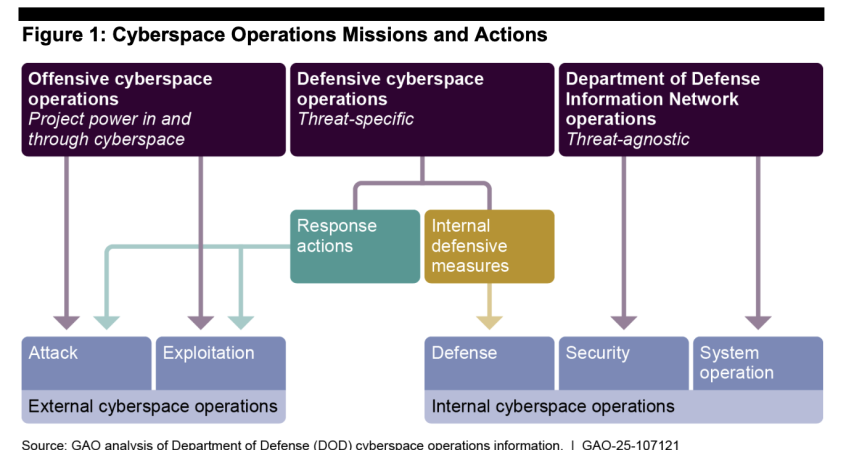

But what exactly does the U.S. military cyberspace enterprise look like? The new GAO report presents a digestible survey of the field. Generally, military cyber actions fall into three categories:

- Offensive cyberspace operations: conduct cyberspace attacks and exploitation aimed at gaining unauthorized access to enemy networks or destroying enemy systems

- Defensive cyberspace operations: defeat specific threats that have bypassed, breached, or are threatening to breach DOD Information Network security measures

- DODIN operations: operating, maintaining, and sustaining military information networks and securing them against a broad range of threats.

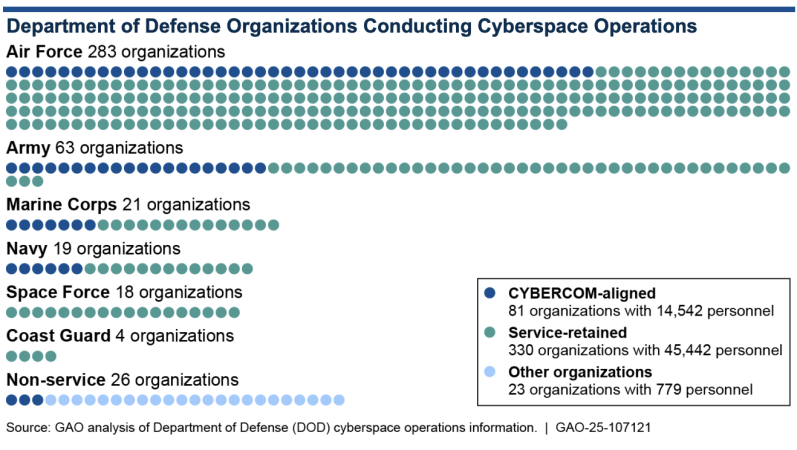

Military cyber forces generally perform those services either for CYBERCOM, for their own service, or for non-service components such as the Defense Threat Reduction Agency and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

The lion’s share of military cyber organizations (75 percent) are retained by their respective services, where they defend, maintain, or expand their services’ information networks or carry out offensive cyberspace operations. A smaller group (18 percent) works for CYBERCOM, which has a broader scope of defending both Pentagon information networks and U.S. critical infrastructure, as well as working with other combatant commands. The smallest group (5 percent) provide cybersecurity to non-service components such as DARPA.

GAO pointed out that there are plenty of similar functions among these groups, and that’s not always a bad thing, given the scale and complexity of military cyber operations. But the enterprise might get inefficient “when multiple agencies or programs have similar goals, engage in similar activities or strategies to achieve them, or target similar beneficiaries,” the report said.

Three potential areas of unnecessary overlap are:

- Organizations within each service providing similar budgetary, personnel, policy, and training support to cyber forces

- Military service training courses: each service has a cyber defense analyst course, GAO noted, so the Defense Department “may be paying for the same thing twice or more.” The military has joint training programs for other career fields such as public affairs and explosive ordnance disposal.

- CSSPs, where 23 separate CSSPs perform largely the same function across the services, which could be an area for consolidation, GAO said.

GAO left the ball in the Pentagon’s court to figure out how to address these areas of overlap. One of GAO’s two recommendations was for the 18-month-old office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Cyber Policy to assess whether similar cyber training courses can be consolidated and made more efficient. The second recommendation was for the assistant secretary to study opportunities for consolidating CSSPs.

The Defense Department agreed with both recommendations.