News last fall that SpaceX owner and CEO Elon Musk restricted the Ukrainian military’s use of his Starlink satellite broadband service to stymie an attack on Russian forces highlighted the extraordinary power wielded in that war by a single business owner with some outlandish ideas.

But beyond the antics and the angst associated with Musk and his controversial views, Starlink and its competitors are leading tectonic shifts in the commercial market for global satellite communications (SATCOM)—and driving emerging geopolitical risks for nation-state customers, including the U.S.

In the past five years, the private sector satellite market has mushroomed. Global connectivity, like earth observation, is now available from a small but growing international ecosystem of private sector players, including the low Earth orbit (LEO) constellations operated by Starlink and competitors OneWeb and Amazon’s Kuiper.

In some ways, this is nothing new, former Space Force deputy chief technology and innovation officer Charles Galbreath said. The U.S. military has for decades purchased as much as 90 percent of its SATCOM from the private sector.

“And I see that growing,” added Galbreath, a retired colonel who spent 30 years working on U.S. military space operations and is now a senior fellow at the Mitchell Institute’s Spacepower Advantage Center of Excellence.

SATCOM as a ‘Hybrid’ Capability

Just this past week, the Pentagon listed SATCOM as one of the half-dozen space mission areas it sees as inherently “hybrid”—where it will seek to use both private sector and government capabilities. “Whether that’s SATCOM, whether that’s imagery, whether that’s on-orbit servicing in the future, you name it, the commercial market is going to continue to grow. And the DOD, and particularly the Space Force, wants to continue to leverage that,” Galbreath said.

What is new, according to Space Force officials, is how global businesses are increasingly balancing international commercial or consumer markets against government and military contracts from the U.S. and its allies.

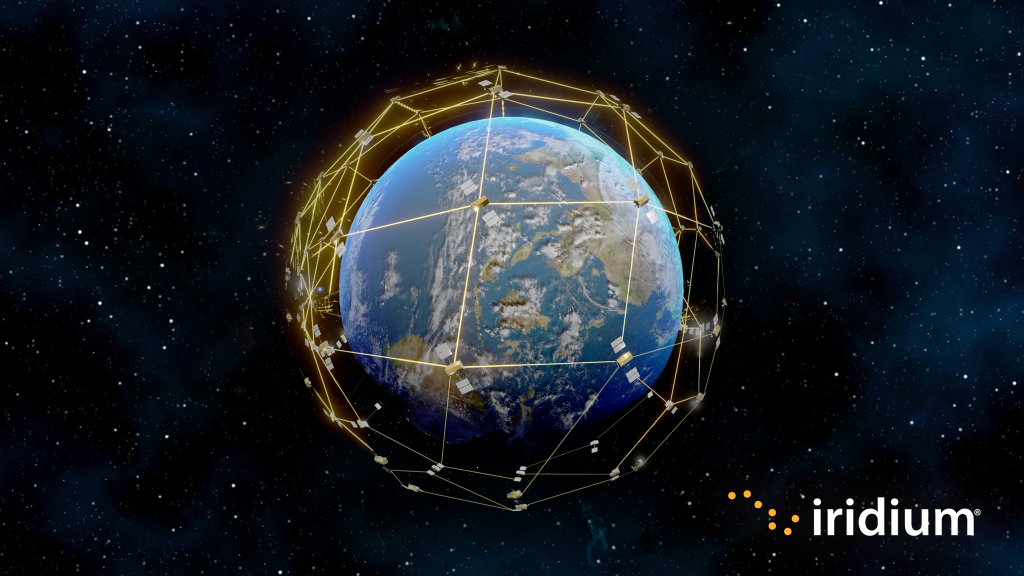

Even established satellite providers like Iridium, which has had a LEO constellation for a quarter century, are expanding their commercial services to better serve small- and medium-sized businesses in sectors like the Internet of Things (IoT), reducing their dependency on government and military customers.

Increasingly, commercial SATCOM providers are “paid by the global population, not paid by the Space Force, so their loyalties are to their bottom [line] dollar,” said Barbara Baker, the deputy program executive officer for military communications and position, navigation, and timing (PNT) at Space Systems Command.

But these New Space commercial players are also more innovative, developing new capabilities which the U.S. military could use, she told Air & Space Forces Magazine on the sidelines of SATELLITE 2024, a major space industry trade show in Washington, D.C.

“They’re not only innovating, they’re innovating way faster. They found a [global] marketplace” that could fund research and development, Baker said. “DOD can take advantage of that.”

A Starlink Moment?

But in taking advantage of those innovative SATCOM capabilities, Galbreath said, the military needs to weigh possible geopolitical risks, like Starlink’s geofencing in Ukraine. Officials should “look at who else was using that system, and if they don’t like the other partners, back away, because there will be multiple providers available,” he said. Competition gives the government options, he added.

The risks are front and center in space acquisition at this moment, he noted, because of “the limited set, a growing set, but a limited set right now, [of suppliers for key services.] That places a lot more power in the hands of the folks that can deliver capabilities today.”

For instance, Galbreath noted, Starlink is the only company currently able to offer global broadband connectivity via a mega constellation in LEO.

“What is unique about Elon Musk’s situation with Starlink is right now they’re the only ones providing that type of capability,” he said. “As other competitors enter the market, and his monopoly is eroded, his outsized personal influence will quickly erode as well.”

Nonetheless, Galbreath also noted that walking away from Starlink might not be so simple, even once its competitors are fully operational. SpaceX, which launches and operates Starlink, is a major partner for the Space Force given its status as the only purveyor of reusable rockets and one of a small handful of launch providers.

“So he does have that additional leverage that’s potentially in play, which is why having a robust and industrial base with multiple providers is so critical” across all space mission areas, Galbreath said.

Multiple vendors offer the government options for different kinds of missions, said Lt. Col. Christopher Cox, branch chief for SATCOM, PNT and, space data network architecture at the Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space Acquisition and Integration.

“There’s different types of [satellite] networks that are used for different purposes,” he said in a brief interview. A commercial broadband internet connection like Starlink might be appropriate for “morale and recreation. Those networks have one set of security considerations, one set of reliability considerations.” But the networks that supported operational missions are “high layer, exquisite, bespoke,” he said, “And the ultimate requirement for DOD is to be able to support that whole range of networks.”

Deciding which services can be used for which purposes isn’t always straightforward, noted Baker. “Depending on anti-jamming capability, depending on the threat environment, depending on issues like, which signal do I need? If it’s [Military Ka band], I can’t get that through commercial, so we have to look at all that … But it’s a tricky question, because it has to be part of an integrated picture.”

The Real Change

More tricky still, the new LEO constellations offer more than just point-to-point connectivity. Traditional geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) satellite communications operated on a simple “bent pipe” principle, where the user terminal points up at a single satellite at a fixed position in the sky, which then sends its signal straight back down to a ground station connected to the network.

But because satellites in low Earth orbit move quickly across the sky, LEO constellations require orchestration: Satellites, user terminals, and ground control stations all need to be networked together and remotely managed.

This means the days are gone when the military could just buy bandwidth from satellite providers to power its own networks, according to acquisition officials and space industry executives.

“The real big change over the past few years has not been to LEO, but to [SATCOM as] a managed service,” Rick Lober, head of military and government business for satellite operator Hughes, said during a SATELLITE 2024 panel discussion.

A managed service puts a great deal of power in the hands of the provider, as the Ukrainians have discovered with Starlink, explained a former U.S official who has worked as a contractor there. “What they love about it is, it works out of the box,” they said. “You take it off the truck and in five minutes you’re online. … But that [user experience] is enabled by the same granular network management that makes it possible for him [Musk] to play God, to reach out and say, ‘You can use it here, but not there.’”

Starlink did not respond to a request for comment submitted through its parent company SpaceX.

Playing God

These issues are not unique to Starlink, Matt Desch, CEO of Iridium, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. His company has run a LEO constellation providing managed services to customers including the U.S. government and military since 1998, but in most market segments they do not compete directly with Starlink.

Desch said he would be very reluctant to turn service off in any area, because doing so would cut off all Iridium devices there used by everyone—including humanitarian aid organizations and emergency communication systems for planes and trains.

Such a move could be a blunt instrument, especially in wartime, when the front line could move suddenly and unpredictably.

“In situations where other operators may be trying to make a choice between activities they like and those they don’t like,” he said, “I think they’re probably doing as much damage as they’re doing good by either turning the service off or leaving it on,” in a given locality.

The problem, Desch pointed out, is in any given geographical area where bad actors might be using Iridium service, good guys are too.

“In most cases we’re used more by the good guys than the bad guys,” he said. “And regardless, it’s impossible for us to tell them apart since we don’t provide direct service to the customer.”

Because Iridium is a network wholesaler, Desch explained, “We go to market through hundreds of third-party resellers,” and have limited visibility into who the end users are.

The safety-critical applications powered by Iridium and the communications they enable in disaster zones are still a humanitarian imperative anywhere on the planet, he said.

Iridium’s global coverage “is literally a life-or-death issue,” Desch added.

But he stressed that, “if I’m ever told that ‘Terrorists are using one of your devices,’ and given information for that specific device and asked to turn it off, it wouldn’t take anything more. … We would of course respond to lawful orders and would jump on any requests like that.”

Restricting service more broadly, though, would undermine the work the company had done over many years to build partnerships with its big customers.

“We’ve worked hard to build up trust in our service that we do things in a very consistent way. Legality is our starting point. We are an extremely ethical company that is transparent as a public company. We are balanced and fair, and as apolitical as we can be,” he said.

Taiwan

Other governments also appear to be hedging their geopolitical risk, up to and including supporting or launching their own Starlink competitors. The role of Starlink in the Ukraine conflict and Musk’s previous comments that Taiwan was an “integral part” of China, were reportedly a wake-up call for Taipei—especially when the terrestrial networks and undersea fiber optic cables which provide the island’s connectivity would be vulnerable in a shooting war with China.

According to the New York Times, Taipei broke off negotiations with Starlink when Musk balked at a requirement that he form a joint venture, with a majority local ownership, to operate on the island.

Officials say Taiwan is exploring its own LEO constellation, and has already launched two experimental satellites. In the meantime, a Taiwanese telecommunications provider has struck a deal with Starlink’s competitor OneWeb.