The U.S. homeland is vulnerable to air and missile attack across the Arctic because the network of ground, air, and space-based defenses guarding those approaches have atrophied over time, according to a new paper from AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

President Donald Trump’s Golden Dome defensive shield will have to modernize those systems if the system is to counteract threats like hypersonic missiles and waves of hard-to-detect cruise missiles flying across the polar region.

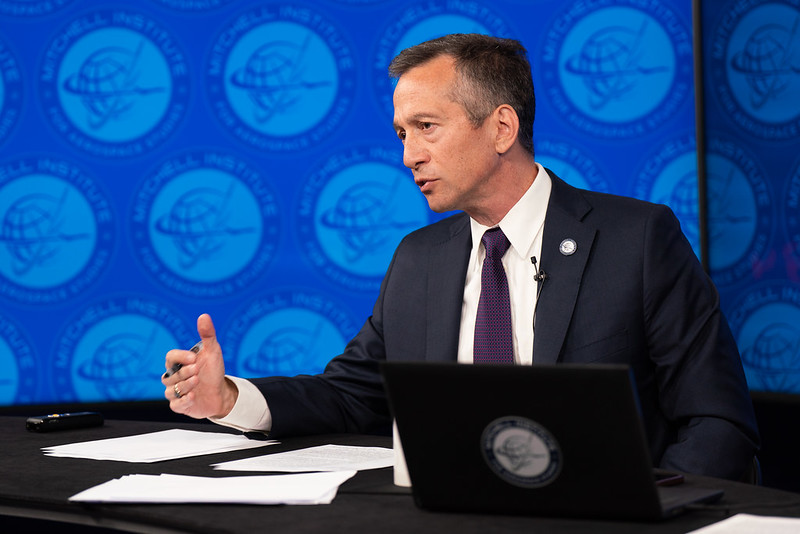

U.S. defenders would have less than 60 minutes to stop a hypersonic missile launched from a Russian aircraft against couldNew York or Washington, D.C., wrote retired Air Force Brig. Gen. Houston “Slider” Cantwell, a senior resident fellow for Airpower Studies at the Mitchell Institute, in the policy paper. Titled Homeland Sanctuary Lost: Urgent Actions to Secure the Arctic Flank, the paper calls for securing the country’s Arctic flank. Russian bombers could launch a salvo of advanced KH-101 cruise missiles over the Arctic and “return to base without detection by the existing radar system, the North Warning System,” Cantwell said at a Sept. 4 Mitchell Institute event releasing the paper. “The missiles would also likely remain undetected due to their low altitude flight paths. Existing early warning radar detection systems are simply inadequate given these modern threats.”

The former head of U.S. Northern Command, Gen. Glen VanHerck, now retired, joined Cantwell for the rollout, sharing his perspectives as the one-time boss of the North American Aerospace Defense Command. “The fact exists that both Russia and China have the capability to inflict kinetic attacks on our homeland,” he said. “We need to become more resilient. We need to be able to take a punch in the nose, whether it’s a cyber attack or a conventional kinetic attack, and get back up and come out swinging.”

To ensure early warning and a chance to intercept incoming threats, Cantwell said, the U.S. must invest in a new layered sensor network covering all domains—air, land, sea, and space—andmust improve information sharing among the Defense Department and other federal, state and local agencies. Strengthening partnerships with allied countries on Russia’s arctic front door is also key to reducing vulnerabilities in the region, the paper adds.

“It is time for the nation to rebuild its northern tier defenses,” Cantwell wrote. “Bolstering arctic security will be essential to any plan for reducing the risk of attacks on the continental U.S.”

To defend the homeland and deter attacks on the United States, the paper recommends:

- Accelerate the fusion of all-source data to enhance Arctic domain awareness.

- Configure “Sky Range” unmanned aircraft for dual-use homeland defense aerial surveillance.

- Lead international commitment to E-7 Wedgetail acquisition.

- Accelerate modernization and replacement plan for the Northern Warning System.

- Accelerate fielding of space-based Arctic domain awareness capabilities.

- Create a new Assistant Secretary of Defense responsible for “Arctic Security.”

- Foster NATO’s Arctic focus and direct partnership with NORAD.

During the Cold War, the U.S. and Canada developed an advanced early-warning network consisting of 138 radar sites with roughly 800 aircraft dedicated for air defense. But with the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union and the 2001 terrorist attacks on America, the country’s focus shifted away from integrated air defense.

“Defense priorities changed; homeland defense was still the priority, but resourcing took a back seat,” Cantwell said. “Shortfalls accelerated following 9/11, and the United States reoriented its posture to the Middle East. … NORAD defensive systems atrophied.”

Today, the situation has grown so bad, he said, that “in many cases, we wouldn’t know of an aerial attack until the missiles impacted their targets.”

The backbone of North American airborne early warning is the North Warning System, a network of 47 radar sites across northern Canada constructed in the late 1980s. Designed to detect high-flying conventional aircraft, it is ill-suited to spotting low-flying or stealthy aircraft, long-range cruise missiles, or drones, the paper states.

“The North Warning System, when it was designed, was certainly state of the art. Today, it’s a picket fence that missiles can navigate their way through,” the paper quotes VanHerck as saying. “The Department of Defense must budgetarily prioritize systems that can directly defend the homeland by deterring and defeating multiple means of aerial attack.”

The paper calls for a ground network of modern over-the-horizon radars with much greater detection ranges and covering more airspace than earlier systems. To be effective, it argues, they should detect targets at distances between 600 and 1,800 nautical miles. But such complex over-the-horizon radars will take years to develop and require joint support from both the U.S. and Canada.

Space-based radar systems can provide an additional layer of threat detection, but the technology may still be years from being operationally relevant. Space-based Airborne Moving Target Indicator (AMTI) technology promises to one day detect and track airborne threats but is still some years away.

The Space Development Agency is developing its Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture, expected to provide data relay and missile warning and tracking from low-Earth orbit. That system could become the backbone for space-based command and control, sensor-to-shooter connectivity, the paper states.

The report opposes moves to to cancel the E-7 Wedgetail, an advanced early-warning aircraft intended to replace the E-3 Airborne Early Warning and Command System (AWACS).

The Air Force needs the E-7 because the E-3s, old and based on the 1960s Boeing 707 platform, are old and unreliable, suffering a 55 percent availability rate. Keeping that fleet airborne through the mid-2030s will cost nearly $10 billion,” according to the paper.

The E-7 Wedgetail will provide essential targeting and command and control relay capabilities,” Cantwell said. “The aircraft flexibility is going to allow responsiveness to our evolving threats or to degraded land systems, it plays an essential role and must be placed back in the Air Force budget.”

Existing unmanned aircraft such as the MQ-9 Reaper and the RQ-4 Global Hawk also offer a promising near-term solution to Arctic awareness, the paper states. The Test Resource Management Center at the Grand Sky section of Grand Forks Air Force Base in North Dakota operates an extensive fleet of MQ-9s and 27 RQ-4s. These aircraft are primarily tasked to monitor hypersonic weapons testing but could be tasked with additional surveillance activities between tests, the paper states.

For Golden Dome to work, its information architecture must be able to support rapid information exchange across agencies, intelligence sharing, and automated solutions to overcome technical barriers.

“We must streamline information flow,” Cantwell said, citing the Global Information Dominance Experiment conducted under VanHerck’s leadership in 2020.

Van Herck said the idea initially was to connect all the sensors and focused shooters.

“I changed that very quickly, to sensor to decision maker to collaborate globally,” VanHerck said. “Homeland defense does not start in the homeland; it starts with my fellow combatant commanders and our network of allies and partners.”

By the fourth and final experiment, VanHerck said “we had multiple allies and partners playing. All 11 combatant commanders were able to collaborate in real time to develop a global information and intelligence picture simultaneously.

“The operators were developing deterrence or defeat options, while … the logisticians were verifying those options were executable with the right fuel, the right weapons, the right airplanes, ships in the right places,” he recalled. “Today that takes days and weeks, and it’s done on a regional basis. We were able to do that in hours and collaborate across the globe to make that happen.”

The Defense Department’s Maven Smart System also shows promise, the report states. It ties headquarters together across combatant command boundaries while also tying together information across discrete information domains at different classification levels.

Maven forms the “connective tissue between operators and sensors, weapons platforms and decision makers, breaking down barriers across organizations,” Cantwell said. “The [Defense] Department has got to continue to prioritize software and systems aimed at connecting warfighters and databases across classifications, across different departments and across international borders.”

VanHerck said rebuilding America’s Arctic defenses are a critical part of making Golden Dome a success. “With that said, it starts with policy,” VanHerck added. “What are we going to defend [against]? From whom? How many threats? … You can’t defend against 4,000 inbound nuclear missiles, so there needs to be some tough decisions on policy, and that’s where we must start.”