FARNBOROUGH, U.K.—Meeting with reporters, industry leaders, and military officials from across the world at the Farnborough International Airshow, engine-makers GE Aviation and Pratt & Whitney laid out their competing visions for the future of F-35 propulsion in July.

While executives from both companies agreed that the fifth-gen fighter’s engine program needs a change, they continue to pitch sharply different approaches—and assessments of what the problem itself is.

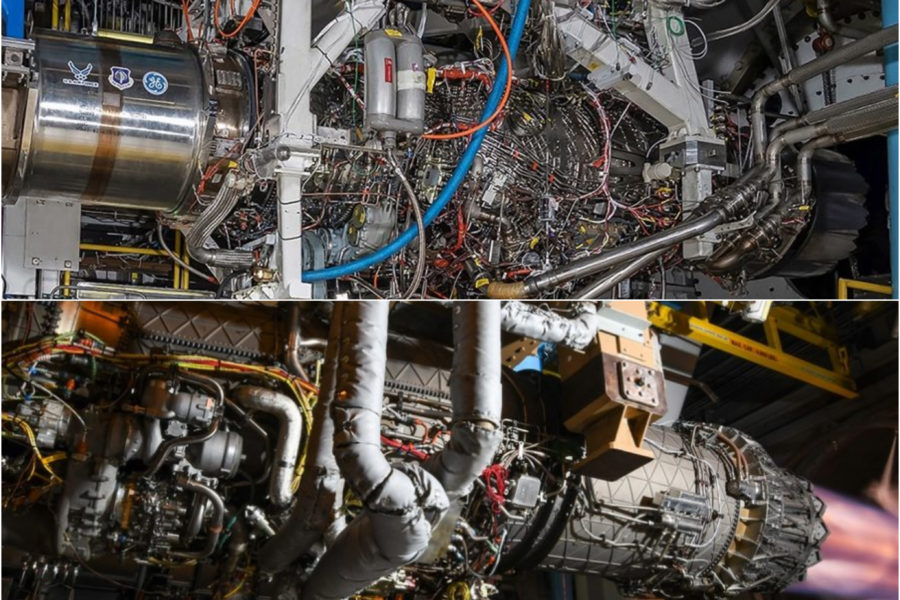

GE is pushing to replace the current F135 engine with its cutting-edge XA100, developed as part of the Air Force’s Advanced Engine Transition Program and described by David Tweedie, GE’s general manager of Advanced Combat Engines, as providing a generational-level jump in capabilities.

Pratt & Whitney is offering what it calls its F135 Enhanced Engine Package, which Jennifer Latka, vice president of the F135 program, likened to a “block upgrade” that will be cheaper, faster to field, and more than sufficient for the Joint Program Office’s needs.

Both contractors took extra steps to publicly make their case, as Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall has hinted that a final decision could be coming soon. Pratt & Whitney used advertising on London buses to appeal to decision-makers visiting Farnborough, while GE participated in a public forum session.

Need for Change

Leading Pentagon officials and lawmakers have expressed frustration with the F-35’s sustainment problems, particularly with the engine, for years now. And the issue seemingly reached a critical point when Air Force leaders said in July 2021 that more than 40 of the service’s F-35As were without an engine due to maintenance issues—nearly 15 percent of the fleet.

Acknowledging those problems, Latka pointed to several factors, including increased demand for power and cooling for other systems on the jet, delays in standing up maintenance depots, and a sustainment enterprise that differs from previous fighter programs.

Still, the program has improved as of late, she said.

“We continue to work on reliability improvements, to keep the engine on the wing even longer,” Latka said. “And we’re in a very, very good place right now. We have improved the aircraft-on-ground situation by 75 percent between January 1 and now, so we’re far, far exceeding the program’s objectives.”

Yet as leaders now look to the future of the F-35, they face a decision in how drastically they want to overhaul the engine, depending on whether they simply want better thermal management or even more.

Adaptive Engines

As part of AETP, both GE and Pratt & Whitney have developed prototypes of adaptive engines—propulsion systems that Tweedie says will provide “next-generation capability.”

In particular, GE is claiming that the XA100 would improve the F-35’s range by 30 percent, its acceleration by 20 to 40 percent, its fuel efficiency by 25 percent, and its thermal management capabilities by 100 percent.

Tweedie laid out three reasons for those jumps: the engine’s ability to transition between modes optimized for thrust and for range, a third stream of air to help with cooling, and “advanced materials and manufacturing techniques” such as ceramic matrix composites and 3-D printing that produce parts that are lighter and can withstand more heat.

Thus far, GE has built two prototype XA100 engines. Tweedie declined to disclose exactly how many hours of run time those engines have gotten during testing at both GE and Air Force facilities but said it was in the “hundreds.”

“We’re very pleased with the results so far on both the engine tests. And the more we run it, the more we really like this engine,” Tweedie said. “And it’s meeting the aggressive and challenging goals that were set out there. And when we conclude this phase of testing, we really believe we’ve met the objectives of the Air Force, which were to not do an incremental improvement but to fundamentally make that generational change.”

That generational change could be delivered “by the end of the decade,” Tweedie said. That timeline is slightly longer than one proposed by Congress in the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, which called for every Air Force F-35 to get AETP engines by 2027. Tweedie previously said such a goal is “certainly within the art of the possible.”

Getting there, however, would require coordination and cooperation between the Joint Program Office, the various services, and Congress, Tweedie acknowledged, and there is a significant problem in that regard: The XA100 will fit on the F-35A and F-35C, but its ability to integrate onto the short-take-off-and-vertical-landing F-35B is unclear.

“We really focused on doing the A and the C [models],” Tweedie said. “Now the B model does present certainly unique integration challenges, without question. But now that we have the prototype design laid flat, it’s in the test cell, it’s running, we know what we’ve got. … We are under contract from the Joint Program Office, working collaboratively with Lockheed and Rolls-Royce on the lift fan, to look at, what can we do with the XA100? And how can we leverage that into an F-35B? And what would be the capability improvements that we can provide to that platform? And what are the incremental costs in development and time associated with coming out with a B model capability leveraged from what we’re doing on the A and the C?”

The study is still ongoing, Tweedie said, but GE hopes to have data by this fall.

Pratt & Whitney, meanwhile, is adamant that neither the XA100 nor its own AETP engine, the XA101, will work on the F-35B.

“No matter what anyone tells you, it’s not going to fit inside a STOVL,” Latka said. “There’s a third duct in the XA engines, both ours and our competitor’s, and that physically doesn’t work. … There’s still a tremendous amount of design work to do on the aircraft because the new engine is 1,000 pounds more, and all of that structural analysis hasn’t been done yet.”

Tweedie declined to confirm how much heavier the XA100 is but said GE has worked with F-35 maker Lockheed Martin and the Air Force to ensure that the added weight will be “certainly tolerable and not a challenge from an integration perspective.”

EEP

While Pratt & Whitney is down on the idea of an AETP engine on the F-35, the engine maker believes it will be used on a future fighter.

“In my opinion, the AETP program, thank goodness for it, because we need to stay ahead of our adversaries as it relates to propulsion,” Latka said. “It’s one of the few advantages we have from a defense standpoint. And that program really matured sixth-gen technology for propulsion, and it will absolutely be used, whether it’s GE or Pratt & Whitney. That is what we’ll be moving into NGAD.”

But such technologies aren’t needed for the F-35, Latka argued, and installing them in only some of the F-35 fleet will create costly, separate supply chains and sustainment enterprises. In speaking with international delegations at Farnborough, Lakta said a common concern was maintaining “that international alliance, right, and keeping the glue together.”

In contrast, Pratt & Whitney is arguing that its “Enhanced Engine Package” will solve what it believes is the F135’s main issue—thermal management.

“The problem statement, even though there’s no official requirement, it’s sort of derived, is around this cooling issue. … You would never in a million years put a new engine, brand-new engine, into an aircraft to solve the cooling issue,” Latka said. “And that’s why Pratt & Whitney is offering the enhanced engine package, which is a core upgrade.”

That’s not to say that some elements of the XA101 couldn’t become part of the F135. Being part of AETP, as well as the Navy’s fuel burn reduction program, Pratt & Whitney has “the ability to leverage those investments and pull a little bit of the new stuff onto the existing engine,” Latka said.

Latka also claimed that the future block upgrades won’t be necessary over the course of the F-35’s life cycle—projected to reach 2070—because the core upgrade at the heart of the Enhanced Engine Package will produce more than enough thermal management to handle future systems that may be added to the fighter.

“In the future, if you want to bring even more into the jet, you don’t even need to do this again,” Latka said. “You’ve still got margin and headroom, and it allows the partnership to remain across the As, Bs, and Cs and the international partners because everybody maintains the same configuration [of] propulsion system.”