Contaminated powdered nickel used to manufacture some Pratt & Whitney commercial engines—and prompting an accelerated pace of inspections—may also have made its way into F135 fighter engines, but the risk is considered low and the F-35 enterprise has “already taken significant steps to mitigate the risk,” the Joint Program Office told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

RTX, parent company of Pratt & Whitney, said in an earnings call this week that powdered nickel used to make parts for some of its commercial engines—notably the PW1100 that powers many Airbus A320neo airliners—was contaminated with other material in batches dating from 2015 to 2020. The “microscopic” contaminant could cause parts made with the material to fail. Officials called it a “rare” problem.

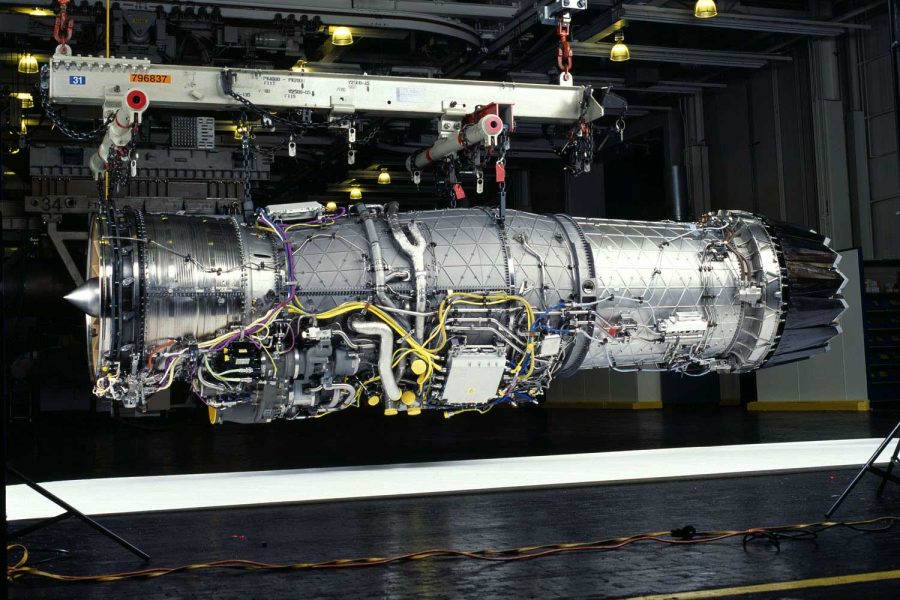

Company officials did not say at the time whether the material was used in the manufacture of other Pratt products, such as fighter engines, but said it would accelerate, at its own expense, the rate of inspections of commercial engines using parts known to have been made with the material. Many of these are high-pressure turbine discs. The issue was described by officials as a “quality escape.”

The problem was discovered and corrected in new items two years ago, and Pratt has been monitoring those parts made with the contaminated material since, during regularly-scheduled inspections. New testing has indicated inspections are needed sooner, company officials said.

Asked if the contaminated metal powder constitutes a problem for the F135 engine used on the F-35 fighter, a JPO spokesperson said its propulsion management office “has been aware of the powdered nickel contaminants issue since 2021 and have already taken significant steps to mitigate the risk. The suspect contaminants have been identified and were removed from the forging process in September 2021.” The JPO did not identify the steps it has taken.

Pratt’s assessment of the risk “was reviewed by the JPO and we concur with the preliminary assessment that the fleet is at low risk on the JSF Hazard Risk Criteria at this time,” the program office said. It expects “minimal maintenance impact to the fleet” and said it will work with Pratt “to ensure all safety protocols and mitigation plans are properly utilized.”

Neither the JPO nor Pratt identified specific parts on the F135 engine that may have the contaminated material.

In its own statement to Air & Space Forces Magazine, Pratt & Whitney said through a spokesperson that “we’ve had zero F135 maintenance issues related to powdered nickel contaminants. Our military customers are aware that we monitor for it, and they are fully aligned with our mature safety protocols and mitigation plans, which we will continue to update as required.”

RTX chairman and CEO Greg Hayes told financial reporters the inspections will inconvenience commercial operators and the company will compensate them for taking some of their aircraft out of service unexpectedly.

An inspection regime “focused on the high pressure turbine discs” of the PW1100 “is already in place and Pratt is developing plans to optimize shop … capacity within its network to complete these inspections as quickly and efficiently as possible,” he said.

“Current production of powdered metal parts is not impacted and Pratt will continue to deliver both new engines and new spare parts across all product lines,” he added.

“We’re on top of it, we’ve got this,” he said. “It’s going to be expensive. We’re going to make the airlines whole as a result of the disruption.”

But, he added, “it’s not an existential threat. …It is a problem [like] we have every day, and we’ll solve it.”

Company officials said the powder is manufactured in one of Pratt’s New York facilities, processed in a company forge in Georgia, and then made into parts such as turbine discs. They said that over 3,000 inspections of PW1100 parts have been made already, and about 1,200 more need to be made on commercial engines. The number of suspect parts found to be in need of replacement is “less than one percent,” Hayes said.