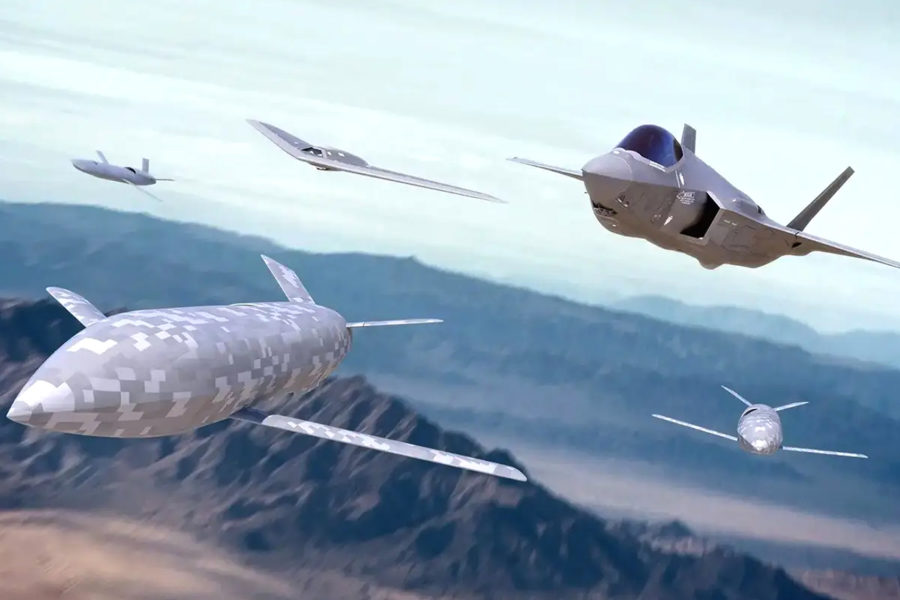

Moderately capable—and moderately costly—Collaborative Combat Aircraft would be extremely valuable in a war with China, so long as they are “additive” to new crewed aircraft already planned and used independently and not just “tethered” to those crewed aircraft, according to a new report from AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

A series of wargames run by the Mitchell Institute showed that when used by the U.S. Air Force in large numbers, CCAs—autonomous drones meant to supplement the manned fleet—compelled China to expend large numbers of missiles, created beneficial chaos in the battlespace, and overall were a cost-imposing factor on the adversary, participants said Feb. 6.

Retired Col. Mark A. Gunzinger, retired Maj. Gen. Lawrence A. Stutzriem, and Bill Sweetman summarized the wargames’ findings in a paper, “The Need for Collaborative Combat Aircraft for Disruptive Air Warfare.”

The CCA program, still in its infancy but expected to grow quickly, represents “an opportunity for the Air Force,” Gunzinger said during an online event. Given that the Air Force fleet is the smallest and oldest it’s ever been and there is a growing mismatch between “the supply and demand for Air Force airpower,” Gunzinger said, an injection of low-cost CCA drones in large numbers to match or overwhelm China’s air assets makes USAF potentially dominant in such a fight.

Gunzinger further emphasized the importance of low costs.

“It’s unreasonable to assume” the Air Force will be able to match China aircraft for aircraft, missile for missile, and so it must invest in an “asymmetric” approach which will disrupt China’s operating plan and impose costs upon it, he said.

In the wargames, three separate “Blue” teams were free to ask for CCAs ranging from “exquisite,” $40 million-plus autonomous aircraft with capabilities near that of a crewed fifth-generation fighter—2,000-mile range, six missiles onboard, very-low observable stealth, onboard radars and infrared trackers, and runway independent—to more basic craft, under $15 million apiece, with far fewer weapons and stealth.

The result: teams scarcely used “exquisite” CCAs in the early days of a fight because of the risk of losing them.

Curtis Wilson, senior director of emergent missions at General Atomics Aeronautical Systems, participated in the games and said if a CCA “only needs to last 30 minutes, the cost goes way down” relative to an aircraft expected to serve for decades and built to do so. He also noted that the artificial intelligence needed for such aircraft can be more generic and less capable than would be needed for high-end “exquisite” systems.

Wilson recommended that CCAs be generically designed to take advantage of existing ground support equipment, rather than “bespoke” aircraft requiring significant investment in specialized handling and maintenance gear.

General Atomics is one of five contractors that have been selected to design and build CCAs by the Air Force.

Independently, all the teams involved in the Mitchell wargames chose to use large numbers of moderately-capable, moderately priced mid-range CCAs. These autonomous airplanes sharply reduced the risk to crewed aircraft by soaking up adversary missiles, and China was forced to “honor” each one as a threat that could not be ignored, Gunzinger said.

Their deployment across a wide range of austere air bases, some launched from aircraft or islands with no runways, also compelled China to meter its use of ballistic missiles against the usual well-established operating bases, he noted.

Moreover, Blue threats “attacking early from every axis” vastly complicated China’s defense problem, Stutzriem said, and forced China to maintain a high pace of defensive operations around the clock.

“There is a need to break from the mindset that the CCA always operates in support of crewed aircraft,” Gunzinger said. “CCAs that are appropriately designed to have the right mission systems [and] the right degree of autonomy, can also be used as lead forces to disrupt the enemy’s operations.”

Still, when CCAs were used cooperatively with crewed aircraft like the F-35 or the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter, “it made the fighters better” at accomplishing their missions, Mitchell fellow Heather Penney said.

Robert Winkler, vice president of corporate development and national security programs at Kratos Defense and a wargame participant, said CCAs added considerably to crewed fighter survivability.

Participants from industry, the Air Force and other experts participating in the wargames “unanimously agree” that the CCAs must be “additive and complementary” to crewed aircraft programs already in the pipeline and not a substitute for them, Gunzinger said.

“They’re not going to reduce the Air Force’s requirements for F-35s, NGAD, and B-21s and other critical modernized systems,” he said. Their maximum combat value “will be realized by taking full advantage of the attributes of crewed and uncrewed aircraft, that each bring to the fight.”

Asked if CCAs should have their own squadrons and organizations or be blended with crewed combat aircraft organizations, Gunzinger said this was a heavy topic in post-games analysis.

The conclusion, he said, was that “we need to build future units that consist of both CCA and fighters …bombers, maybe even tankers … So they can operate every day like they’re going to fight, so they can develop the tactics, techniques, procedures, concepts and so forth.”

At the same time, when employed, CCAs don’t need to be “co-located with fighter units or bomber units,” Gunzinger said. They could be crated up and pre-positioned at austere fields, ready for use at need.

Winkler noted that CCAs work best when they are positioned “inside the first island chain” of China’s sphere of operations, rather than operating at long ranges. Doing so increases their operating tempo and further taxes China’s ability to respond, he said.

While the Air Force considers how it will organize and use CCAs, Gunzinger stressed that it is important to recognize that “as the capabilities increase, so will your costs.” Stealth and high-end sensors “all add up to more cost, just like other aircraft, so the secret sauce is developing CCA forces” with the right mix of capabilities.

Certain capabilities are crucial—Stutzriem said a “major insight” of the games was that CCAs must have enough survivability “to reach their weapons launch point.” CCAs that weren’t stealthy enough to survive obviously played little role in the battle.

The report authors recommended that the Air Force:

- Determine the sweet spot of capabilities for the bulk of CCAs and develop a cost-effective mix for the future force structure

- Develop operating concepts for CCAs, such as going after high-value targets and compelling an enemy to expend weapons against them

- Treat CCAs as force multipliers and not substitutes for new crewed systems in the pipeline

- Acquire CCAs “at scale” in this decade

- Give CCAs enough survivability to reach their weapon release points

- Determine what support and launch location needs are required for CCAs in forward areas

- Adapt current munitions to fit on small CCAs and work on miniaturizing new munitions such that many can fit on a small CCA platform

- Persuade Congress of the practical benefits of CCAs and not to “cannibalize” other programs to pay for them

Gunzinger said CCAs “could dramatically change the Air Force’s air combat operations, but it will not happen if the Air Force is forced to rob money from its other modernization programs to pay for it.”