Research Closes in on Reality

When it comes to futuristic weapons, whether directed energy, or hypersonics, or robot troops, or whatever, the joke has long been that they are just “five years away … and always will be.”

Scientists overpromise, national leaders raise unrealistic expectations, and wonder weapons seem to take forever to find their way out of the lab.

That’s changing, said one of the Defense Department’s top technologists. Mark Lewis, director of research and engineering for modernization, said the Pentagon is ready to retire the “and always will be” gag for good.

“We always said hypersonics is the future and ‘always will be,’ but now it’s here,” said Lewis in his first interview since taking the job in November. “I think [directed energy] is in the same category.”

Lewis oversees 11 technical areas that Mike Griffin, undersecretary of defense for research and engineering, said offers the greatest potential for technology insertions and leap-ahead gains in capability. Griffin brought Lewis in last fall to oversee deputy directors in those 11 areas, each of whom is building a roadmap for how those technologies will make their way into operators’ hands. The 11 areas are:

- Hypersonics

- Directed Energy

- Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning

- Biotechnology

- Autonomy

- Cyber

- Microelectronics

- Fully Networked Command, Control, and Communications (FNC3)

- Quantum Science

- Space

- 5G connectivity

The priorities came out of the National Defense Strategy. “It’s a really good list,” Lewis said. “We’re all really big fans of that strategy.” The roadmaps will incorporate “technology, milestones, metrics, and of course, policy issues.” A key aim is to “avoid buzzword science” and work through the ethical implications of the technologies being pursued.

Lewis’ charge to his area directors: “What state do we want to be in, in 2028, 2035, and 2040? And what are the steps that get us there?” Why 2028? Because that’s 10 years after the initiative’s launch in 2018, and it’s a “nice round number.”

Hypersonics

Griffin has publicly pegged hypersonics as his No. 1 priority, and Lewis, the former chief scientist of the Air Force, is a leading expert in the field. Lewis declined to detail how many hypersonics projects are underway in the U.S. military, but “the good news is, people are paying attention, now, right?” he noted.

After almost a decade of growing concern that China and Russia were advancing their hypersonic programs ahead of the United States, it’s now on every armed service’s priority list.

“They’re focused, they’re complementary, the services are doing what best fits their mission, and … we have all the bases covered,” Lewis said. Hypersonics is “a suite of technologies,” he said: “It’s conventional prompt strike systems, it’s tactical systems, it cruise missiles,” and it’s defense against hypersonic weapons, most likely involving directed energy.

“We don’t want to simply duplicate what other people are doing, just because they’re doing it,” Lewis said of competitors such as Russia and China. “We want to do things that make sense for us. Which is almost certainly different from what other [countries] might pursue.”

Lewis declined to discuss the various U.S. military hypersonics programs in detail because they’re classified, but said “it is not a free-for-all.” One of his roles will be to “coordinate and make sure the services and agencies are talking to each other, and they’re spending their resources in ways that complement each other.” These will include the defense laboratories, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, and, “at some point,” the Space Development Agency.

Lewis arrived wanting to see more investment in air-breathing hypersonics, like the DARPA Hypersonic Air-breathing Weapon Concept, or HAWC, because the Pentagon had already made a sizable investment in the successful X-51 program, which wasn’t being vigorously followed up. “I think there’s a lot to be gained from further pursuit of the air-breathing solutions,” he said.

China featured DF-17 hypersonic missiles at its 70th anniversary parade in the fall. Were they real or mock-ups? “I think we have to take them at face value,” Lewis said. “I didn’t see any evidence of cardboard.” He added, “There obviously was some strategic messaging, there.”

Lewis singled out the Army as particularly strong in hypersonics, saying the service “has a really well-thought-out plan, in my opinion, on how to get from the laboratory to operational systems; a really strong focus.” But the Navy also understands that “peer hypersonic systems hold the Navy at risk,” and is giving the technology the attention it deserves. The Air Force continues to move ahead “pretty aggressively, as well.” All the services are sharing, he reported. “For example, one of the things they’re sharing is designs for a common glide vehicle.”

There’s also opportunity for “engagement with allies,” such as Australia, which partnered with the U.S. in hypersonics on the HiFIRE program, and which developed the “Stalker Tube,” a wind tunnel used for testing hypersonic vehicle models in a particular regime.

“There is a genuine sense of urgency in our program,” he said, and while testing will begin this year, “we’re not just interested in delivering something quickly. We want to deliver a real capability.” He’s not interested in “onesies-twosies.”

Putting “three missiles in a tube doesn’t do anything for us,” Lewis asserted. “It’s putting tens, twenties, [dropping] hypersonic systems out a bomb bay … having enough defensive systems so we’re effectively protecting our air bases. That’s what we need to be envisioning.”

What’s the timeline? Lewis won’t say, but “we definitely want to do it as quickly as possible.”

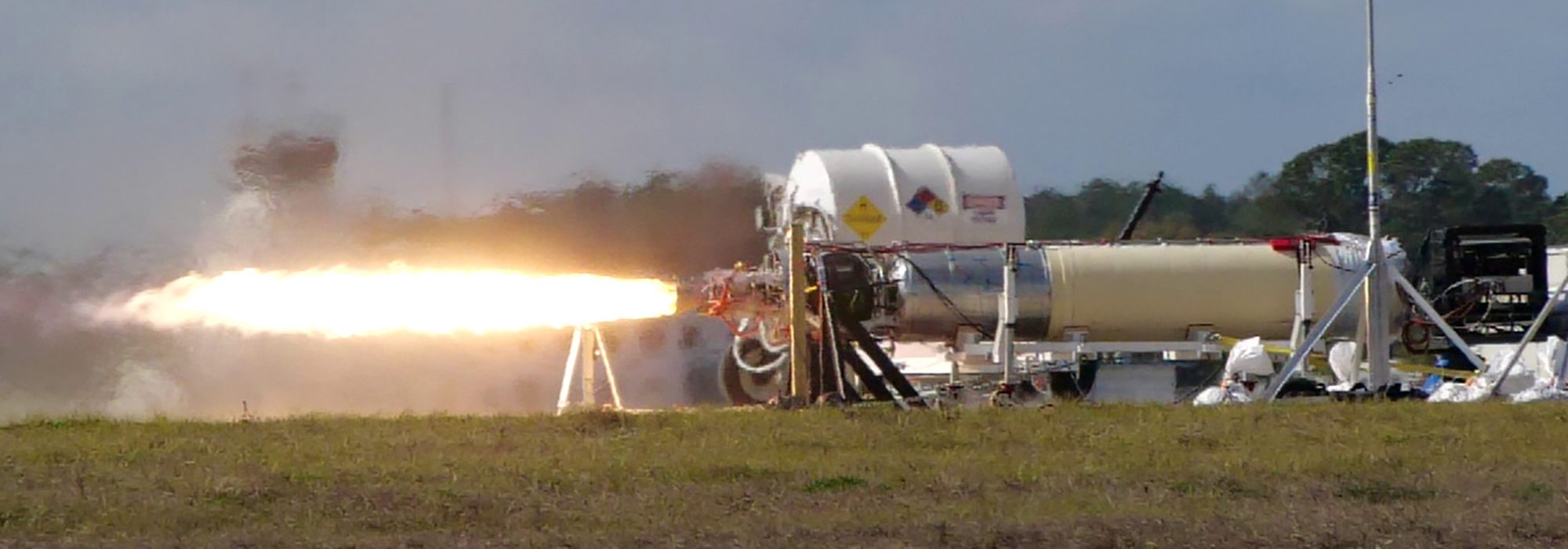

Directed Energy

In directed energy—which includes lasers, high-powered microwaves, and other manipulations of the electromagnetic spectrum—“We’re on the threshold of being able to deploy practical …systems,” Lewis said. Lasers have been brought up to “reasonable power levels … in the multi-tens of kilowatts range,” and the concepts of operation have matured. During his previous stint in the Pentagon, a lot of laser concepts “basically substituted a laser for a kinetic weapon … like, a laser as a gun,” he said. “Now I think we understand that we would use directed energy in different ways than you would use kinetic systems.”

There are certain things that “frankly, might be easier to shoot down with a laser than a gun.” Asked if that meant unmanned aircraft, he responded, “You said it, not I.” Does the military have the mobile computing power to make the concept work? “I think we do, yeah.”

It’s important to make such systems practical. If a tactical laser system requires a tractor-trailer size generator, that’s not very useful, he said. But “if we can get it down to reasonably compact form, fit, function,” the utility goes way up.

AI and Autonomy

The future of electronic warfare is likely to be in artificial intelligence; machines sensing frequency changes and adapting in near-real time, much faster than a human being can do. Beyond such functions, “we would use autonomy to help us make decisions, not make decisions for us,” Lewis said. “We are not marching down the path of ‘The Terminator.’ ”

Are “loyal wingman” robotic aircraft flying with manned combat airplanes close at hand? “I think we’re pretty close,” Lewis said. “I think there’s tremendous value in it.”

Lewis worries that pervasive use of the term “AI” is rendering it meaningless. It’s better to think in terms of “machine learning,” he said, because that will “allow us to break through and understand information” in large volumes, at high speed.

Technology is “pointing us in the direction of … swarms,” according to Lewis, but “we’re not completely removing humans from the loop. … We don’t ever view a time when we’ve got, say, a fully autonomous ‘F-30-whatever’ making its own decisions about blowing things up. And that’s a really important distinction.”

Biotech

Although there have been some well-publicized examples of Defense dollars creating “power suits” and exoskeletons that enable humans to lift extreme weights, there is no “Iron Man” in the near future, Lewis said. For one thing, “power suits are power-limited. … Iron Man’s got that magical power source that we haven’t invented, yet.”

He also cautioned that no one should be worried about technology road maps that recommended “enhancing” people.

“Human beings have been enhanced by technology for centuries,” he said. Eyeglasses, hearing aids, night vision goggles, and prosthetic limbs are all human enhancements that did not involve reengineered human brains or flesh.

“We think about what technology tools we can bring to bear that will … help human beings make decisions, provide them with the right sensors and information, the right way to process it and present it … how to improve knowledge,” he said. “We are not talking about implants, or … plugging people into computers with wires coming out the back of their skulls. … We are not on a path to create Frankenstein.”

Blockchain, Quantum, and Cyber

The promise of blockchain and quantum computing is that information is stored in such small and discrete ways that any tampering would be immediately obvious. Are the days of hacking nearly over?

“No. At least, I don’t think so,” Lewis said. Blockchain will make it harder “for someone to break in, and we’re more likely to know about it,” he said, but hacking is likely to be “something we’ll always guard against.”

The Defense Department in late January released new cybersecurity policies for defense contractors. Lewis said the department will always discuss some kinds of security information “with our trusted partners and trusted vendors, [but] some things we won’t be able to discuss.” The emphasis will be on sharing in order to get the best ideas from industry, and so industry knows where the Pentagon wants to go.

“If we don’t discuss it at all, then what good is it?” he asked rhetorically.

Space

Space technology has tended to focus on miniaturization, better power sources and more reliable rockets over the years, and to that Lewis would like to add “making space more resilient.”

What was once a benign environment is now rife with potential threats. “Right now we’ve got some vulnerabilities if people start taking out our space assets,” Lewis said. “I want to be in a situation where, if people take out our space assets, all they do is make us angry, not hurt us. That’s my goal.”

One way to achieve resilience is to simply broaden the network so that an adversary is discouraged from even bothering to try to knock it out. “Having better … and lower-cost access to space … building-in redundancies and being able to replenish, that’s all part of where we’re going,” he said.

So is space resilience all about sheer numbers? “It’s how many, and how we use them, and how they interact with each other, and with other parts of our command and control network,” Lewis answered.

Lewis said he has an “amazing team of assistant directors” who are technical experts in their fields. He and they are well-engaged with Congress, which he said is willing to invest in long-term approaches where necessary.

“The folks on the Hill are our friends … they understand what we’re trying to do,” Lewis said. He tells them, he added, that he believes “we’re the single most important office in the Pentagon because it’s worrying about the future. And while everyone thinks they’re the most important—that’s why they do it—I haven’t gotten a lot of pushback on that.”