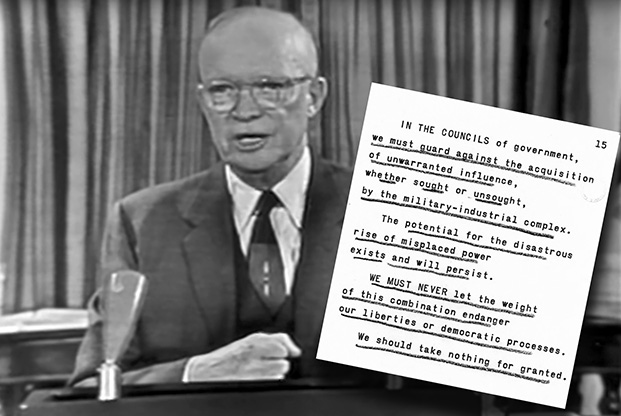

Dwight Eisenhower during his farewell address to the nation Jan. 17, 1961, and excerpts from the address. Photos: National Archives

President Dwight D. Eisenhower had a strong grasp of the importance of national security and the issues surrounding it. He was a five-star general and arguably the most distinguished military commander of the 20th century.

At the same time, he deplored the arms race and described it in terms of resources that might have been allocated instead to building schools, hospitals, and housing. He was also known to be angered by the clamor of the “munitions lobby” for increased military spending. None of this, however, set up an expectation for the central theme of Eisenhower’s farewell address, delivered from the White House on national television Jan. 17, 1961, three days before he left office.

The most famous line came about halfway through the speech: “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex.”

The phrase lives on and on, more so than anything else Eisenhower ever said. It is still quoted regularly almost 60 years later. It never seemed to matter that the words were not characteristic of his way of speaking, or that they were crafted for him by speechwriter Malcom “Mac” Moos.

After he left office, Eisenhower said little more about it. It is not perfectly clear, from either the context of the speech or anything said separately, exactly what Ike’s intended message was.

It is usually forgotten in the popular awareness that Eisenhower led into his “unwarranted influence” line with an acknowledgment that the nation could “no longer risk emergency improvisation of national defense” and that the strategic realities of 1961 created an “imperative need” for a large military force and “a permanent arms industry.”

Eisenhower did not demonize the military-industrial complex. He cited the potential for abuse and advised caution. The flaming accusations came later, from others. Sen. George S. McGovern (D-S.D.), a contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968, declared that the “mounting influence of the military-industrial complex” was “the most serious internal threat facing the United States.”

The speech has been taken captive by ideologues who use it for their own purposes. “The concept of the military-industrial complex has become a rhetorical Rorschach blot—the meaning is in the eye of the beholder,” says journalist James Ledbetter, who studied the issue at length for his book Unwarranted Influence in 2011.

MERCHANTS OF DEATH

The notion of a military-industrial complex was somewhat reminiscent of the “Merchants of Death” movement, popular in the 1930s, which claimed that the munitions industry had influenced the US decision to enter World War I and had made vast profits from it.

In 1934-1935, Sen. Gerald P. Nye, a populist Republican from North Dakota, held 93 hearings that produced colorful headlines but little substance. He might have gone on longer but Congress cut off his funding when he accused President Woodrow Wilson of concealing essential information about the declaration of war in 1917.

Prior to World War II, numerous efforts and congressional actions sought to limit the “profitability” of war. It took extraordinary leadership from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to instigate mobilization of industry leading to the “Arsenal of Democracy” during World War II.

When the Arsenal of Democracy was running at full tilt, it incorporated just over 47 percent of US economic output. War production peaked in 1943 and declined sharply in 1944. The defense industry was almost completely dismantled after World War II.

However, the time line for military preparedness had changed. Nuclear weapons, long-range bombers, and eventually ballistic missiles left no time for an extended buildup of arms in the event of war.

In his “Chance for Peace” speech in 1953, sometimes cited as a “bookend” with his farewell address, Ike said that, “Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies—in the final sense—a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and not clothed.”

In a similar speech in 1958, Eisenhower lamented the rising defense budget and “tragic penalties” imposed by the “utterly wasteful” armaments race. “All of us deplore this vast military spending,” he said. “Yet in the face of the Soviet attitude, we recognize its necessity.”

President Eisenhower (center) discusses the flight demonstration of the Boeing B-52 prototype with Cabinet and Boeing officials in the early 1950s. Photo: Boeing via AFA

THE NEW COLOSSUS

Before World War II, most US military ordnance was produced in government arsenals. During the war, much of the workload shifted to factories—the automobile industry being a prime example—converted from civilian output but converted back again when the war ended.

The large standing forces of the Cold War required a permanent arms industry to equip and support them, and by 1958, less than 10 percent of US weapons production was by government arsenals. Thirty of the 50 largest industrial corporations were defense contractors, either full time or partially. The defense program was a smaller share of total government spending than it had been in World War II or the Korean War, but in 1961, still accounted for 50.8 percent of federal outlays and 9.3 percent of the gross domestic product.

About a third of the defense budget went for procurement and research and development. Congress saw to it that the contracting bounty was spread around to home districts all across the country.

Concerns about military-industrial influence took a different tack when Congressional Democrats accused Eisenhower of allowing a “bomber gap” to develop in 1956 and then a more serious “missile gap” in 1959.

Strangely, the origin of the missile gap controversy seems to have been a background statement in January 1959 in which Secretary of Defense Neil H. McElroy speculated that the Soviets would achieve superiority in ICBMs within the next year. Ike contributed to the tale himself, saying at a press conference that the Soviet ICBM program had started first but that US scientists and services were “catching up as fast as they can.”

Nevertheless, Eisenhower was convinced that the missile gap story remained alive because the arms industry and the military services, especially the Air Force, were feeding information and rumors to his critics. At another press conference in June 1959, he confirmed that he had spoken to members of Congress about the influence of the “munitions lobby.”

It was not until after the election that the missile gap was revealed to be nonexistent.

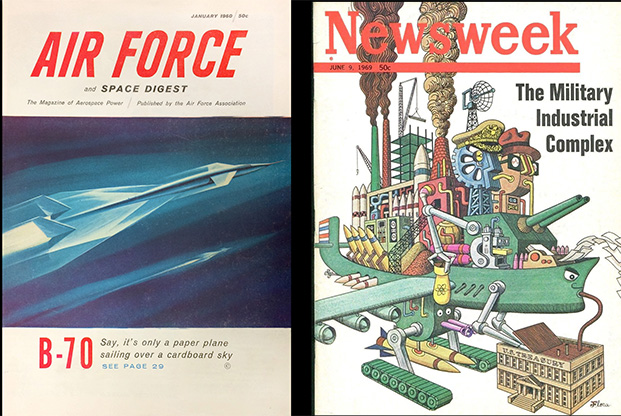

Air Force Magazine, an Air Force Association publication, showed an illustration of the short-lived B-70 bomber. The Eisenhower administration was angered by AFA’s efforts to restore the curtailed B-70 bomber.Newsweek in 1969 wrote about the “military-industrial complex.” The phrase gained traction far beyond its importance in 1961. Photos: AFA; Newsweek via Nosworld

THE MALCOM MOOS TRIO

Moos, longtime professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, came to the White House in September 1958 as chief speechwriter. He described himself as an adherent of “left-wing Republicanism.” In 1954, he had been co-author of a book, Power through Purpose, which according to Ledbetter “described the harmful competition for resources between national defense and peacetime needs.”

There were two other speechwriters: Steven H. Hess, whose specialty was “the political stuff,” and Ralph E. Williams, a Navy aide to the president. When Williams asked Moos if he could be of help, “Mac, never having been in the military, was delighted to add an at-hand expert on national security to his team,” Hess said.

Moos showed Eisenhower a book of famous presidential speeches, including George Washington’s farewell address. Ike said that when he left office, he would like to make such an address to Congress and the American people. Moos set up a special file for ideas on a farewell speech. Work on the address—which would eventually go through 29 drafts—began in May 1959.

The speechwriters’ office got copies of magazines from military associations and trade press. Moos was fascinated by the aerospace publications, particularly Aviation Week and the Air Force Association’s Air Force Magazine. He brought the magazines to Eisenhower’s attention.

“Repeatedly, I saw Ike angered by the excesses, both in text and advertising, of the aerospace-electronics press, which advocated ever bigger and better weapons to meet an ever bigger and better Soviet threat they had conjured up,” said James R. Killian, the president’s science adviser. (Killian is credited with talking Eisenhower out of directing his criticism at a “military-scientific complex.”)

Williams is sometimes cited as coining the “military-industrial complex” phrase but he generally defers to Moos. “I’m sure the president never thought about either the phrase or the concept itself until Mac Moos put the first draft under his nose,” he said. Williams believed that “it struck a responsive chord” in large part because Ike “had been stung by the Democratic candidates’ criticism of the ‘missile gap’ during the 1960 election and the ‘bomber gap’ in 1956.”

Eisenhower, Williams said, was “outraged at the antics of the cabal consisting of Air Force officers, aviation industry lobbyists, trade associations, and Congressmen promoting arms programs beneficial to their districts who regularly fed ammunition to his critics.” Eisenhower considered expanding the term to “the military-industrial-congressional complex,” but decided against it.

According to Hess, the primary writers of the speech were Moos and Williams, with “massive additions and corrections” by the president’s brother, Milton S. Eisenhower.

B-47 bombers under construction at the Douglas Aircraft facility in Tulsa, Okla. Photo: AFA

CATCHING FIRE SLOWLY

Moos suggested that the speech take the form of an address to Congress, but Eisenhower wanted to make his report directly to the nation. Television cameras were brought into the Oval Office and the President spoke from the White House.

He cited the importance of American leadership in a dangerous world, saying “we face a hostile ideology—global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method.” This led to the requirement for large-scale military preparedness and also to its inevitable corollary, the potential for “unwarranted influence” by a military-industrial complex.

“Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together,” he said.

Considering the impact the speech achieved later, the initial reaction was subdued. A Washington Post editorial noted, “Eisenhower said little that was new” but “he said it with good heart and good feeling.” Of 20 questions at Ike’s press conference the next day, only two were about the “peacetime military establishment” and the “scientific-technological elite” and they were softly put.

Columnist Walter Lipmann was energized by the speech, which he reinterpreted though the filter of his own opinions. To Lippmann, it was about the “threat to the supremacy of the civilian power.” Government “can and should impose a strict military discipline on the statements and speeches issued by the Chiefs of Staff and by local commanders throughout the world,” he said.

As the 1960s rolled on, however, condemnation of the military-industrial complex became widespread. Sen. J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, complained that the complex “has become a major political force.” Sen. Eugene McCarthy (D-Minn.) urged the Senate to “put some kind of limit on the power of the military-industrial complex.” Popular economist John Kenneth Galbraith said the defense industry should be nationalized.

Eisenhower himself said little further about it. In Waging Peace, the second volume of his White House memoirs, Eisenhower devoted only two of the 741 pages to the issue and most of that was quoting from the farewell address.

In the latter years of his presidency, Eisenhower said, “I began to feel more and more uneasiness about the effect on the nation of tremendous peacetime military expenditures” and that “under the spur of profit potential, powerful lobbies spring up to argue for even larger munitions expenditures.”

In retirement, Eisenhower lived on his farm near Gettysburg, Pa. His grandson David, who lived there too, recorded his observations in a book, Going Home to Glory.

“Eisenhower later developed a kind of split personality about the most controversial speech of his life,” David Eisenhower said. “Among his business friends and military colleagues, Eisenhower became defensive and self-critical about the speech. … Yet with others, Eisenhower was assured and precise about his meaning, and confident that the idea required forceful expression.”

OFFENSES OF THE COMPLEX

Not satisfied with Eisenhower’s assessment of potential problems, the critics piled on with a litany of alleged actual offenses. Among the main categories were these:

Undue influence on policy. Two examples were mentioned frequently. The aerospace industry hoped for a reversal of the decision to cancel or curtail the B-70 bomber. To columnist Marquis Childs, the publicity and lobbying campaign demonstrated the power of the “invisible lobby.” In fact, no great “unwarranted influence” was exerted. The B-70/RS-70 program was limited to two prototypes. One crashed and one went to a museum.

In a higher-profile instance, the Air Force Association—sometimes seen as a home base of sorts for the military-industrial complex—adopted a resolution in 1963 opposing the Limited Test Ban Treaty. Childs condemned AFA’s attempt to “sway the debate” but the fireworks came from investigative reporter Fred J. Cook, who thundered that “The Air Force Association, its courage fortified by booze, blondes, and bashes, quite evidently has no qualms about calling for a program of eradication that could be achieved only at the frightful price of mutual nuclear holocaust.” Cook charged that, “there is hardly an area of our lives today in which the military influence is anything less than supreme.”

Perhaps unaware of that, the Senate ratified the treaty, 80-14.

Cost overruns. They happened, but defense programs had no monopoly on them. The interstate highway system—lauded as one of Eisenhower’s greatest achievements—incUrred a cost overrun of 267 percent. In its early years, Medicare overran by 800 percent the cost projection of the House Ways and Means Committee.

Excessive profits, especially by the aerospace industry. Profit can be measured in various ways and comparisons are difficult. However, a New York Times business report in 1962 said that “the earnings rate of the aerospace industry have been lower than that for other manufacturing industries” from 1957 to 1961.

Sen. William Proxmire (D-Wis.)—well known for his “Golden Fleece” awards to government agencies he deemed wasteful—maintained that aerospace profits were more than 10 percent higher than for American industry in general.

To the contrary, a General Accounting Office (GAO) study for the years 1966 to 1969 found that despite some exceptions, defense work was less profitable than commercial work. Historian James A. Huston noted that although defense programs often made less profit than civilian production, the contracts usually involved less risk.

THE UNCEASING ECHO

The defense and aerospace industries diminished with the end of the Apollo space program and the winding down of the Vietnam War. In the 1970s, USAF raised an alarm about the decline of the defense industrial base. The capability for surge of weapons production in an emergency was no longer assured. Only a single supplier was left for some commodities, and for others, the prospect of dependency on foreign sources loomed.

The interval between introduction of new fighters and bombers—once a matter of a few years—stretched into decades. Defense spending dropped as a percentage of both the gross domestic product and of total federal outlays. Numerous defense contractors disappeared; many of those that survived merged with each other.

Even so, the outcry against the military-industrial complex goes on. In 2011, an article in The Atlantic said that, “Judged 50 years later, Ike’s frightening prophecy actually understates the scope of our modern system—and the dangers of the perpetual march to war it has put us on.”

PBS producer Glen Baker declared in 2012 that, “the salute of all things military” struck him as “a cynical ploy to ensure that the military-industrial-congressional-entertainment complex is well fed, even as spending on the rest of society is cut and the debt balloons.”

Jonathan Turley, a professor of law at George Washington University, claimed in 2014 that, “The new coalition of companies, agencies, and lobbyists dwarfs the system known by Eisenhower.”

There is more than a little imagination at play here.

As a share of GDP, government spending on defense has declined from 9.3 percent in 1961 to 3.1 percent today.

The Air Force, previously regarded as the centerpiece of the military-industrial complex—and which launched more than 1,000 bombers on a single day in 1944—has exactly 158 bombers in the fleet today.

Active Duty strength in the 2010s is the lowest since before World War II and 61 percent below the level when Eisenhower made the speech.

It takes some stretching to perceive any kind of a military-industrial threat to society in that.

_John T. Correll was the editor-in-chief of Air Force Magazine for 18 years and is now a contributor. His most recent article, “Revolt of the Admirals,” appeared in the July issue.